Dissatisfaction with the failure to deliver adequate services often results in protests, with Johannesburg being the country’s protest capital. Photo: File

Citizen engagement — the process by which people are involved in public issues — is at the centre of democratic governance. Through voting, protests, attending community meetings and contacting local councillors, citizens can enhance effectiveness, accountability and transparency. But what are the consequences when citizen participation is disregarded?

Democratic participation is meant to influence decision-making processes. But its effect on local governance appears limited. One contributing factor may be how the government interacts with citizens.

For example, planning and budget documents presented by the local government are often lengthy, use technical terminology and are released shortly before public consultations. As a result, the timeframe available for citizens to read, interpret and respond to them is constrained, which restricts the potential for informed input into planning, budgeting, and service delivery.

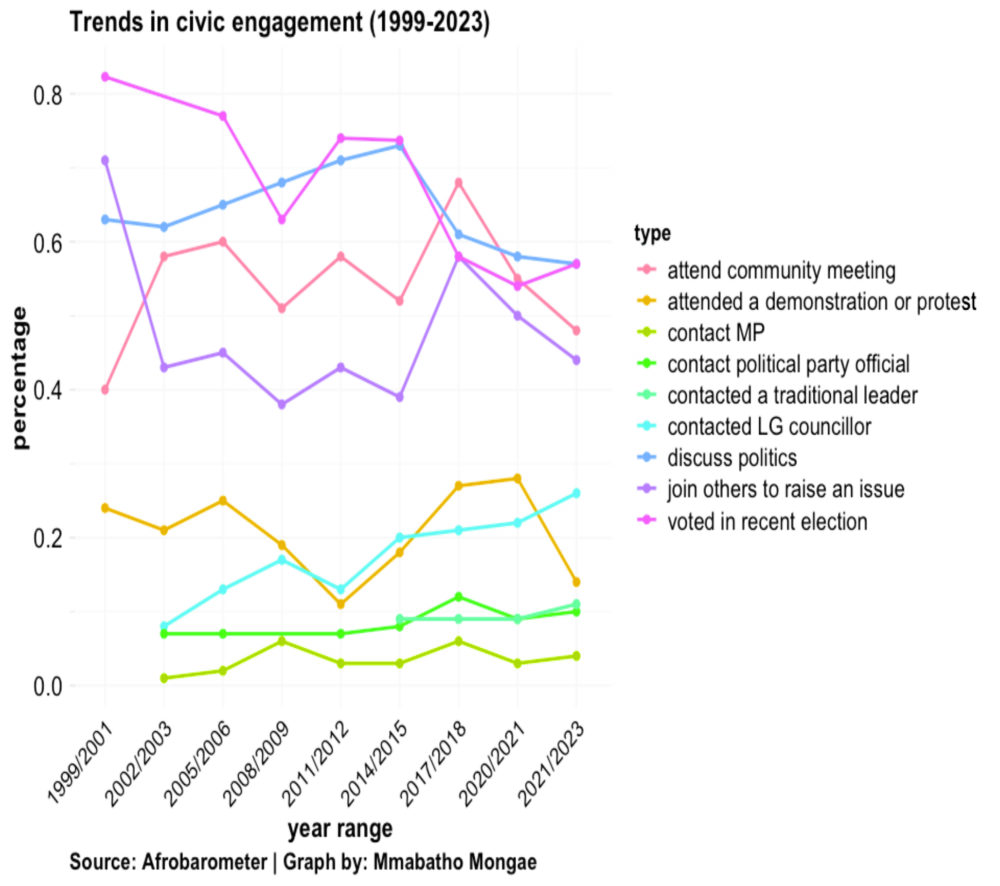

From a data perspective, there is an overall decline in civic engagement. But what does this suggest, what modes of civic interaction are declining and what does this tell us about political behaviour in South Africa?

Civic engagement encompasses multiple political and civic activities. The type of civic interaction that most South Africans participate in may give insight into how they are choosing to engage with the state.

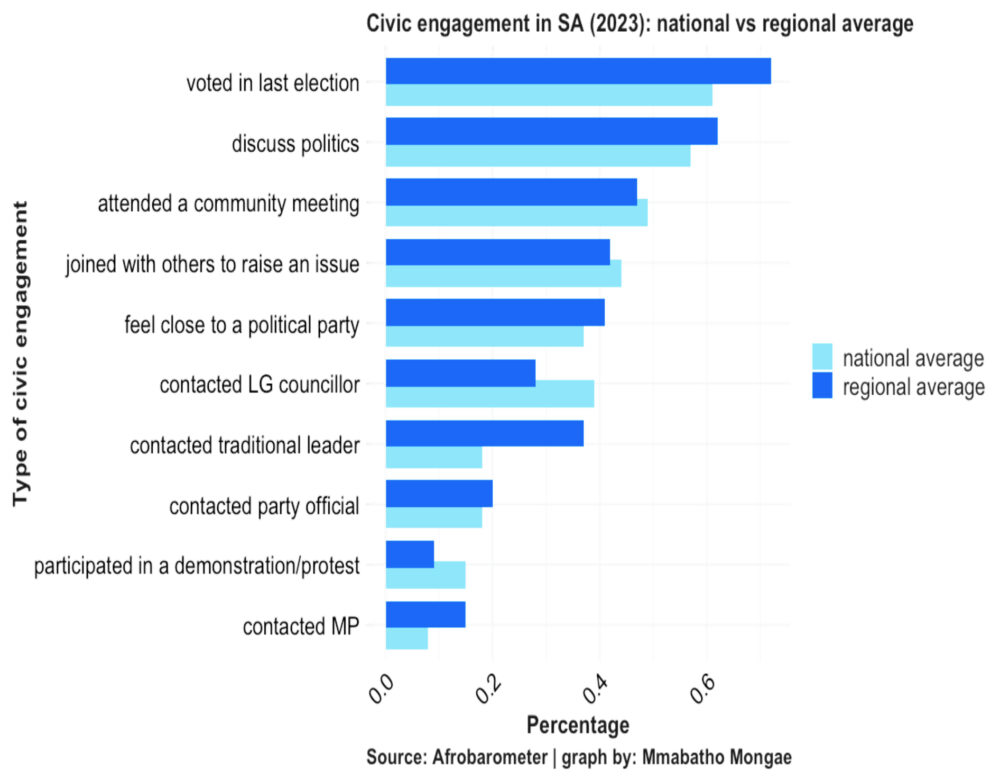

The 2025 Afrobarometer report identifies 10 indicators for civic participation: voted in the last election; feel close to a political party; discuss politics; attended a community meeting; joined others to raise an issue; contacted a traditional leader; contacted a local councillor; contacted a political party official; contacted an MP; and participated in a protest.

Discussions on civic participation often centre on elections and protest action. Elections are usually recognised as the bridge between citizens and politicians, and a continuous decline in voter turnout suggests there is a disconnect between them. Based on this decline, we could deduce that there is growing apathy in South Africa’s electorate. But there are other modes of participation.

Figure 1 compares civic engagement in South Africa to the regional averages. The figure indicates that national responses for attending a community meeting, joining others to raise an issue, contacting a councillor and participating in a demonstration or protest are higher than the regional averages. This suggests participation is deeply rooted in movement-based, consultative, and mobilised forms of civic engagement.

This trend is based in the country’s history of struggle-based activism, where civic engagement was often collective, issue-based, organised around mobilisation — in essence, institutional participation did not inform civic engagement.

Cumulatively, targeting councillors, community meetings and participating in demonstrations shows that everyday governance is what informs how citizens perceive the effectiveness of a political system and what is used to assess democratic governance.

Responses also show that contacting an MP is the least common type of civic engagement (8%), while having voted in the 2019 election (61%) and discussing politics (57%) are the most common types of civic engagement.

Afrobarometer data also suggests that, compared with other types of leaders, contact with local government officials is reported more frequently. One possible explanation is their accessibility, or that their roles position them as primary intermediaries between the state and people.

Local governments are tasked with delivering basic services, enforcing the law and maintaining infrastructure. Given these responsibilities, citizen perceptions of political performance and institutional effectiveness may be shaped by their assessments of local government actors.

Worth noting, from a regional perspective, is that South Africa has one of the highest levels of contact with a councillor (39%). Zimbabwe has an average of 42%, whereas the regional average stands at 28%. This highlights a proactive stance in seeking to address community issues and grievances through formal channels.

Among the 39 African countries surveyed, about one in 10 (9%) of respondents say that they participated in a protest or demonstration, making it the least common mode of engagement. Alongside Cabo Verde, protest action is the third highest in South Africa (15%).

When it comes to civic engagement in South Africa, considerable attention is paid to protest action. But data suggests that respondents who say they have taken part in demonstrations have decreased over the years. In 2017-18 and 2021-23 attendance in demonstrations or protests decreased from 27% to 14%.

The 2015 report by the South African Local Government Association further highlights the nexus between protest actions and other modalities of civic participation. The findings show that individuals who partake in protests are also more inclined to contact their councillors or government officials. This demonstrates that protesters do not solely rely on public demonstrations but also actively contact governmental entities to instigate change.

Furthermore, the report found that those who regularly communicate with their councillors tend to believe that their voices are being acknowledged. These findings further highlight the importance of establishing transparent and responsive communication channels between the government and its constituents. It suggests that when citizens perceive their concerns are being recognised and addressed by their representatives, they are more likely to adopt non-violent methods of engagement.

As depicted in Figure 2, long-term trends in civic and political engagement in South Africa are complex. While there has been a decline across most participation indicators, contact with councillors stands out as an exception, showing a steady recognition of them as accessible points of contact for community concerns, especially compared with other tiers of government.

The data also shows two notable shifts from 2020, coinciding with the Covid-19 pandemic.

First, contact with councillors continued to increase post-2020, possibly because of the need for assistance during the lockdown and service delivery disruptions. Second, the decline in protests is probably a result of movement restrictions. The July 2021 riots in KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng were essentially anomalous, but nonetheless important.

Despite these variations, active forms of participation, such as attending community meetings, protests, community mobilisation, and discussing politics, remain the most prevalent modes of engagement in South Africa. But the overall decline since 2018 is concerning and may reflect public frustration, political fatigue or a perceived ineffectiveness of participatory mechanisms.

Last, the consistently low levels of direct contact with political leaders point to a persistent gap in state-society relations. This suggests that citizens do not view political elites as responsive or approachable, further entrenching disillusionment with formal political institutions.

The trends in civic engagement point to a persistent disconnect between how citizens interact with the state and how the state engages with citizens. Citizens participate through bottom-up, localised and often informal channels, rather than formalised, institutional mechanisms. In contrast, the state prioritises institutionalised, top-down models of participation, often through structured consultations, national dialogues, public hearings or representative forums that may feel distant or inaccessible to many. This divergence limits meaningful democratic engagement, because citizens prefer participatory modalities.

As democracy continues to evolve, the state must recognise and integrate community-driven forms of participation. Rather than relying on protests to be heard or treating grassroots efforts as oppositional, leadership should be people-centred and responsive to lived realities.

In a context of deep inequality and institutional mistrust, state responses must be grounded in everyday experiences — flexible to new forms of engagement, and inclusive enough to bridge the widening gap between state and society.

Dr Mmabatho Mongae is a lead data analyst at Good Governance Africa.