Dream seller: Youths in Nairobi protest on the anniversary of the demonstrations of 2024 in which 60 young people were killed. An increase in income tax, inflation, a higher fuel price and other costs were delivered instead of the jobs and improved lives that President William Ruto promised when he was elected.

(Jared Nyataya /Nation)

‘We sat down after the riots and realised we are losing too many kids. We have gone to too many funerals. There is one thing they can’t do — they can’t out-organise us. So we stopped agonising, and now we are organising to bring about a ballot revolution,” said Boniface Mwangi, a human rights activist and former photojournalist who, in August, announced his presidential campaign to unseat Kenya’s President William Ruto. This came after two rounds of deadly youth-led riots due to soaring cost of living.

Earlier, on a June afternoon in 2024, gunshots and tear gas filled the air as Mwangi and thousands of young Kenyans pushed past heavily armed police and barricades towards parliament. The chants were raw: “Ruto must go. No more taxes.” By nightfall, when the guns fell silent and the tear gas cleared, 60 young people lay dead in the capital’s streets, along with many more injured. Similar riots and police brutality would occur again during the first anniversary of the youth uprising in June and July 2025. The political contract between Ruto and the young Kenyans seemed shattered, giving rise to new ambitions such as those of Mwangi.

For many in Generation Z, the digital-first group that had once given Ruto the benefit of the doubt, this moment marked a significant break. They believed the self-styled “hustler president” would create jobs, lower the price of food and internet, and alleviate their struggles. Instead, they felt the government pushed through a harsh Finance Bill that imposed levies on housing, health and digital transactions, adding to frustrations that were already heightened by joblessness and inflation.

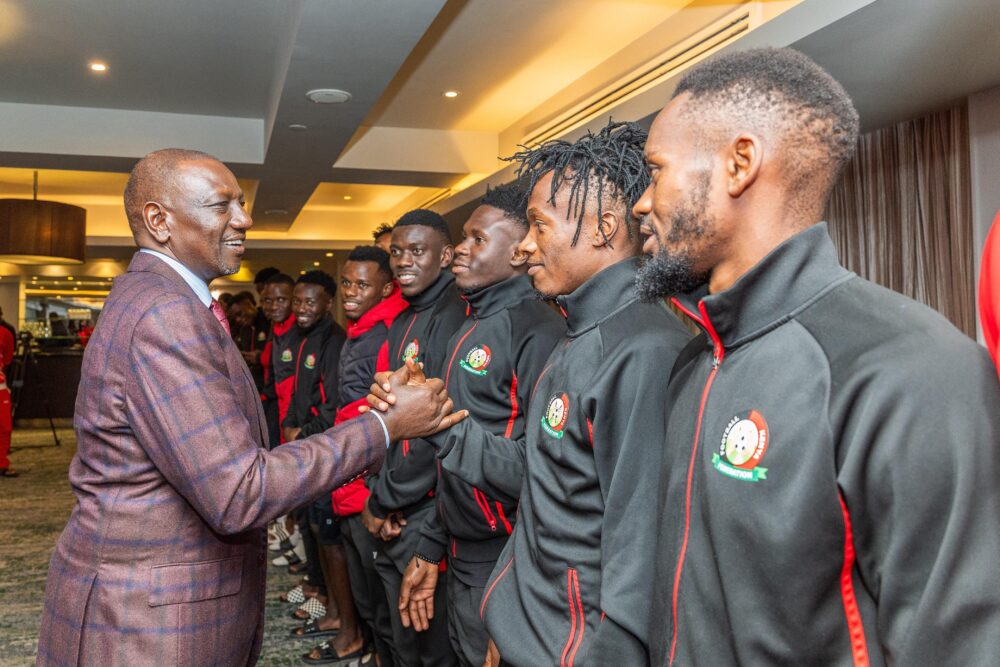

Exactly two years before the 2027 general election, the president, who faced unprecedented unrest from Gen Z, is reinventing himself and his unlikely tool is football. By investing money and personal charm into the Harambee Stars, the national football team, during the African Nations Championship (CHAN), which has just ended, Ruto is trying to present himself as a supporter of national pride and youth aspiration. He awarded each team member $45 000 for reaching the quarterfinals and showed camaraderie with the players and their coach, Benni McCarthy. Whether this strategy can erase memories of broken promises, heavy taxes and bitter political battles is the question that will define Kenya’s next election.

In a surprising move, Ruto acknowledged state excesses and announced the formation of a special committee to oversee compensation for families of Gen Z protesters killed during the riots. The opposition sees this unprecedented action in Kenya’s history of protest crackdowns as Ruto’s path to softening his image as a hardliner, rebranding himself as a leader willing to listen to regain the trust of an electorate mourning their loved ones or coping with scars from tear gas and bullets.

“The hyena cannot be a judge in a case brought by the goat. It cannot be left to President Ruto alone to decide the amount and mode of compensating the victims of police brutality,” said veteran opposition leader Kalonzo Musyoka.

But Ruto and his supporters see the compensation as a broader goal to “heal the nation” ahead of 2027.

Ruto’s 2022 victory relied on a promise to uplift the “hustler nation” — those who worked hard in kiosks, as motorbike taxis and in informal trades. He presented himself as an outsider fighting political elites. This imagery resonated, especially among youth tired of familiar names and disconnected politicians.

But, in two years, that rhetoric fell apart. The government introduced a controversial housing levy, removing 1.5% from salaries for a fund that courts later deemed unconstitutional. Additionally, the new Social Health Insurance Fund, designed to replace the flawed National Hospital Insurance Fund, imposed a 2.75% payroll deduction on workers. With income tax, inflation and high fuel costs added in, Kenyans saw their paycheques shrink.

Promises of cheaper food, millions of jobs and universal healthcare went unfulfilled. Young graduates and school-leavers were caught between lack of employment and the soaring cost of living.

“We were sold dreams and then taxed for them,” a young speaker said during Mwangi’s campaign launch in Nairobi.

The Gen Zs, always online and sensitive to feelings of betrayal, turned their disillusionment and frustrations into street protests. They used their digital platforms to spread dissent through satire, memes and livestreams of police crackdowns. A generation once seen as apolitical was driving the fiercest protests since the clamour for multiparty democracy.

If Gen Z destroyed Ruto’s legitimacy, another crisis threatened his political standing: the fallout with Deputy President Rigathi Gachagua, who was crucial in 2022, bringing in roughly three million votes from Central Kenya. But once in office, he clashed with Ruto’s political allies and accused State House of sidelining him. His confrontational style, which he framed as “truth-telling” to his base, soon faced backlash for perceived ethnic bias.

By October 2024, Gachagua faced an impeachment vote in parliament, the first ever against a sitting deputy president in Kenya’s history. Ruto’s allies pushed it through, and the Senate and the courts sealed his fate. Ruto quickly replaced him with Interior Minister Kithure Kindiki from the same region, but the damage was done. Many in Central Kenya felt betrayed, believing the partnership guaranteed them power.

Gachagua refused to go quietly. In courtrooms and political rallies, he portrayed himself as a martyr, warning of assassination plots and vowing a comeback. Opposition figures, sensing an opportunity, began to rally around him, threatening to take the central Kenya votes from Ruto’s control in 2027.

President Ruto has gone on the charm offensive to win the youth vote’s trust by backing the national football team, the Harambee Stars.

President Ruto has gone on the charm offensive to win the youth vote’s trust by backing the national football team, the Harambee Stars.

Ruto’s response was bold. After the 2024 Gen Z protests, he reshuffled his cabinet, inviting veteran opposition leader Raila Odinga and his Orange Democratic Movement (ODM) party allies into government, dishing out cabinet positions to ODM supporters and experienced technocrats. This was framed as “broad-based government” to stabilise alliances in parliament and project unity.

For Raila, who has run for president five times without success, this arrangement offered influence without the toll of running a government. For Ruto, it was a way to soften opposition blows. But, to many young Kenyans, this alliance felt like betrayal. Raila, once their symbol of resistance, was now aligning with the government.

While the old guard made deals, a generational change is shaping Kenya’s political landscape. Mwangi, known for challenging corruption and police brutality, now seeks a shot at the presidency in 2027. Although the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission has yet to approve his candidacy, his activism resonates with the disillusioned youth.

“Our country is broken and on the brink of becoming a failed state. A vast majority are suffering under the crippling high cost of living, and taxes are suffocating us,” he said.

Faced with crises on multiple fronts, Ruto turned to football as a unifying force. In mid-2025, as Kenya prepared for the CHAN tournament, the president surprised the nation with this offer: each member of the Harambee Stars would receive $83 000 if they won the trophy. Instead, they received half of that after their elimination in the quarterfinal rounds. This was classic Ruto — populist and impossible to overlook, but this time he delivered. After every Harambee Stars game he entered the locker room and delivered $8 300 to each of the team members. The federation’s president remarked that Ruto’s motivation was “half our victory”. For once, the hustler president’s promises became real.

The symbolism was powerful. Where taxes had drained salaries, football filled pockets. Where protests had left scars, the CHAN campaign stirred pride. For the youth who use TikTok and Twitter, images of Ruto celebrating with players and keeping his promises spread faster than any policy speech, tapping into deep emotions and igniting hope, pride and joy.

As the 2027 election approaches and Kenya, alongside neighbours Tanzania and Uganda, prepare to host Africa’s biggest football bonanza — the 2027 Africa Cup of Nations — Ruto’s balancing act becomes delicate. On the one hand, he weighs in as a president of levies, broken promises and heavy-handed actions. On the other, he is admired for football glory, the leader who can provide instant cash and visible pride. If Harambee Stars perform well and Ruto continues to show support for youth-focused initiatives, the tide could turn. But if football success fades while economic struggles worsen, the youth may remember not the locker-room bonuses but the monthly deductions that never ceased.

For Ruto, the stakes are high. His presidency started with the promise of a hustler’s dream, fell into the chaos of tax revolts, and now seeks redemption through football.

The ball is rolling. The whistle for the elections and football 2027 has sounded. The question is whether Kenyans — the youth whose blood soaked the streets — are ready to cheer again or seek a new champion.

Jim Onyango is a communications leader bridging diplomacy, media and policy advocacy across East Africa.