A sea of blue memorial peace race participants were ferried by dozens of boats to take part in the third annual

10km run and walk hosted by the Robben Island Museum Council. Photo: Marlan Padayachee

Time stands still on Robben Island. Seconds become minutes, minutes stretch into hours, and the weight of history settles into the limestone walls that once confined dreamers of a different, democratic South Africa.

As I sat in the museum’s ferry docking station, about to embark on my third visit, my eyes could not miss the power of words from the island’s most famous political prisoner Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela etched on the wall: “It is said that no one truly knows a nation until one has been inside its jails.”

For decades, the island was a towering emblem of punishment—first for enslaved labourers and lepers under colonial rule and later for the anti-apartheid resisters who dared to defy a brutal system.

Thirty-five years after the prison gates swung open and Apartheid’s Alcatraz was reborn as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Robben Island has become one of the country’s most compelling destinations for political, historical and reflective tourism. And yet, on this third visit, the island unveiled itself in a way I had not experienced before—more emotional, more contemplative, more politically charged.

This time, memory walked with me.

Returning as an activist-journalist who once chronicled the liberation struggle, I felt a mix of nostalgia, sorrow, pride, and a profound sense of responsibility. Tourists marvel today at what has become Africa’s equivalent of the Martin Luther King Centre—but for those of us who reported on this painful past, the island remains sacred ground.

A former activist reminded me: “The history of Robben Island cannot be separated from the political breakthrough achieved by prisoner 466/64, Nelson Mandela, with FW de Klerk. Future tours must link Robben Island with Pollsmoor and Victor Verster, where Mandela’s journey to freedom unfolded.”

The picture-postcard view of Table Mountain remains unchanged, the six-coloured national flag fluttering at full mast. Yet the perspective has shifted dramatically.

Imagine hundreds of South Africans—men, women, teenagers—running across a 10-kilometre stretch that was once an unthinkable route for political prisoners. The island came alive during the Third Peace Memorial Run and Walk, expanded this year into a two-day event due to overwhelming demand.

The overarching vision behind this transformation belongs to Dr Saths Cooper—Black Consciousness stalwart, Steve Biko’s lieutenant, former Robben Island prisoner, and now the chairperson of the Robben Island Museum Council. From militant prisoner to custodian of the island’s global legacy, Cooper presided over a weekend that saw 1 500 blue-shirted participants ferried from the mainland in dozens of boats.

I still recall photographing a young Saths Cooper as he walked out of the Durban prison precinct—now the world-class Durban ICC—guitar slung over his shoulder, donning a leather jacket and – free at last. Decades later, he stood on Robben Island’s high ground, watching South Africans of all races embrace an island he once knew only through barbed wire and brutality.

The returning of Cooper’s comrades, Strini Moodley, Dr Aubrey Mokoape (SASO/BPC), and the ANC’s Zulu Moonsamy, Kisten Dorasamy, Billy Nair, Curnick Ndhlovu, Natvarlall Babenia, and dozens others gave me a headstart on the hard life on Robben Island, and how most went in as prisoners and emerged on the quayside as graduates from the University of Robben Island.

Robben Island was once a leper colony where insane females were kept in this now derelict asylum building. Photos: Marlan Padayachee

Robben Island was once a leper colony where insane females were kept in this now derelict asylum building. Photos: Marlan Padayachee

Re-Engineering a Devil’s Island into a Beacon of Hope

Today, Cooper’s leadership is reshaping Robben Island into a dynamic, globally connected heritage site rooted in scholarly excellence, ethical governance, and responsible tourism. What apartheid intended as punishment became, for Cooper, a crucible of intellectual growth, political discipline, and principled resistance.

Under his stewardship, Robben Island has transformed into a living classroom—one that fosters healing, dialogue, healthier lifestyles, democratic reflection, and environmental stewardship. His influence is indelible: the prisoner who once suffered here now shapes its global story.

There is even fresh thinking on the horizon: a proposal to build an overnight hotel, positioning Robben Island as a world-class heritage-tourism hub capable of multi-day stays.

A Living, Breathing Community: Journalists—including a sizeable SABC contingent—athletics officials, runners, walkers and race coordinators spent the weekend occupying prison cells. The island’s community includes ex-prisoners who now serve as guides. Tourists witness the old post office where letters from prisoners’ families were stamped, censored, or silently discarded.

The geography of memory remains deeply layered:

- Cell Five, where Nelson Mandela endured years of confinement.

- The shimmering green Kramat that anchors the island’s spiritual landscape of the Malaysia’s Muslim prisoners.

- The derelict asylum for mentally ill women.

- The leprosy church, stark and white.

- The colonial fire depot standing guard.

- Rows of weather-beaten dwellings that once housed warders and officials.

Freedom—Uhuru—was always a bridge too far. No one escaped.

The ferry ride from the V&A Waterfront remains one of South Africa’s most symbolic journeys. Families, school groups, and international tourists queue anxiously for the crossing—calm today, but once the final voyage for political prisoners leaving the mainland in chains.

Visitors are greeted by a former political prisoner or trained guide, perhaps the most powerful feature of the tour. Their testimonies echo with discipline, unity, censorship, small acts of defiance, mentorship from the old guard, and political education that shaped post-apartheid leadership.

“Where’s Mandela’s cell?” a visitor asked. It remains the emotional centrepiece. Even for me, after two previous visits, its starkness still tightens the throat. How did such a cramped space incubate one of the world’s most influential democratic visions?

Outside, the limestone quarry looms—a place of physical punishment and intellectual rebirth. Mandela called it the University of Robben Island. The stone cairn he initiated remains; visitors continue to lay stones in remembrance.

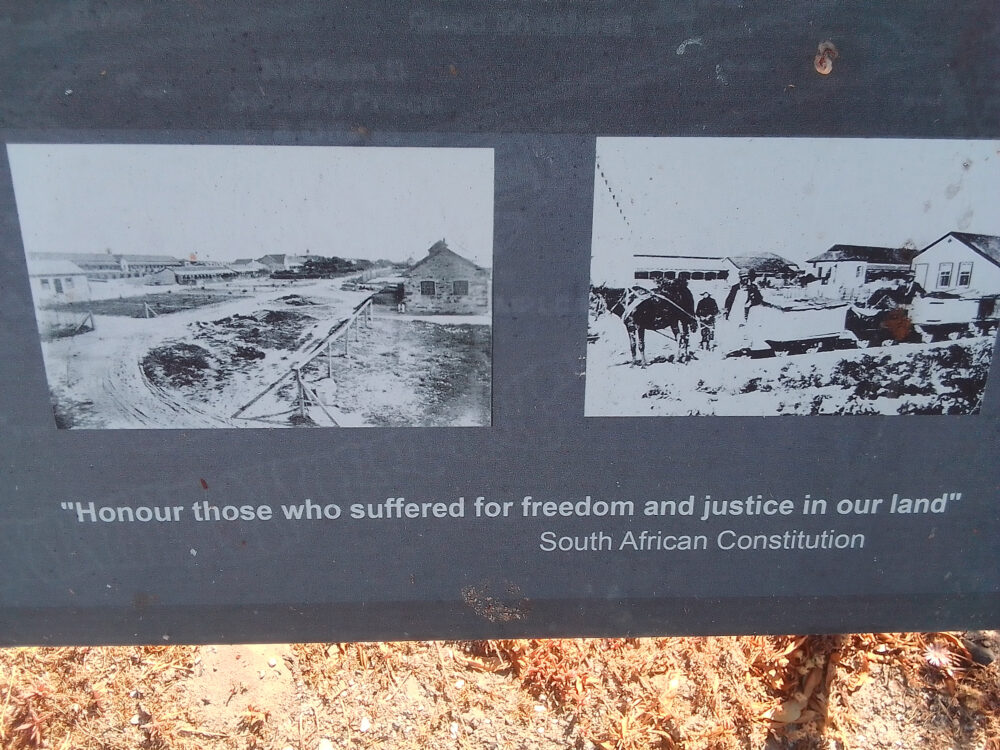

Plaques like this honouring those who sacrificed their lives for freedom are erected across Robben Island – including a new memorial wall with the names of all the political prisoners.

Plaques like this honouring those who sacrificed their lives for freedom are erected across Robben Island – including a new memorial wall with the names of all the political prisoners.

A Barometer of South Africa’s Political Conscience

Robben Island reveals its visitors to themselves. Some walk in silence, others in tears, some in reverence or confusion. Many grapple with a painful question:

What would the Rivonia generation think of today’s South Africa?

The museums have been upgraded—digital storytelling, enhanced curation—but some sections need further refinement. The tension between mass tourism and sacred memory is ever-present.

Yet the emotional impact is undeniable: gratitude, melancholy, hope, and the sobering reminder that liberation is not a finished chapter.

Robben Island is South Africa’s political soul laid bare. Each visit reveals a new layer—historical, emotional, personal. For me, this third pilgrimage reinforced a timeless truth: Freedom was won on the backs of giants, and it is ours to protect. The shack that PAC leader Dr Robert Sobukhe was exiled to has been upgraded with a plaque in his memory.

Robben Island revisited is bittersweet—a journey through our painful past, a celebration of resilience, and a warning not to take democracy for granted. It remains a mandatory pilgrimage for every South African and a global beacon of human rights.

As a tourism high point, it is unforgettable. As a political lesson, it is indispensable.

Historical footnote: In 1961, the apartheid government formally converted Robben Island into a notorious maximum-security prison for political offenders, especially leaders of the liberation struggle, where prisoners were held under the harshest conditions through the 1980s. The prison was officially closed in 1991, with the last political inmates transferred to Pollsmoor and other facilities.

Marlan Padayachee, an associate member of SANEF, is a veteran political, foreign and diplomatic correspondent from South Africa’s transition to democracy, and a recipient of international awards, scholarships and fellowships. He is a freelance journalist, photographer and researcher.