It’s mid-morning on the West Rand’s polluted goldfields and a cold wind blows clouds of fine dust from towering, barren mine dumps. Ngaki Mogopodi glares at the dumps that encircle Kagiso, a township in Krugersdorp.

“It’s us, the people who live here in Kagiso, who have to breathe in all this dangerous dust from these dumps every day,” he says.

“So many people here are coughing, are sick with asthma, and have red eyes from all this dust. How can the government ever have built houses for people here? It’s not safe.”

The tailing dams Mogopodi is referring to, which contain elevated levels of metals and radioactive uranium, were owned and operated by the Mintails group of companies, a gold mining and tailings processing company listed on the Australian Stock Exchange, whose South African operations were liquidated in 2018.

Mintails had billed itself as a rehabilitation venture, promising local residents that it would re-mine and remove a ring of dumps stretching from Krugersdorp to Randfontein. But all it has left behind is a ruined landscape, says Mogopodi.

“These mine dumps are destroying us,” he says. “They are a hazard to the community and there are so many zama zamas [artisanal miners] around now trying to make a living.

“We can’t use the river [the headwaters of the Wonderfonteinspruit] to plant crops because this water is toxic from all the mining waste. There’s no fish, no life in that river. And this is a river that is supposed to help the community.”

Mariette Liefferink, the chief executive of the Federation for a Sustainable Environment (FSE), an environmental watchdog, has swapped her trademark high heels for sensible boots. She trudges to one of the most polluted hotspots near Kagiso, Lancaster Dam in Krugersdorp.

This was once the pristine headwaters of the upper Wonderfonteinspruit, which supplies Potchefstroom with drinking water through the Boskop Dam. Now it is a sterile, poisoned wasteland.

Liefferink points at the dam’s tinged brown-red water: “You can see all the acid mine drainage there. Mintails left it like this. It’s dead.”

She gestures to the metal deposits in the contaminated soil adjacent to the dam. “The black is the manganese, the red is the iron pyrite. You see that yellow or white crust on that soil? It’s all highly soluble and contains elevated levels of uranium.”

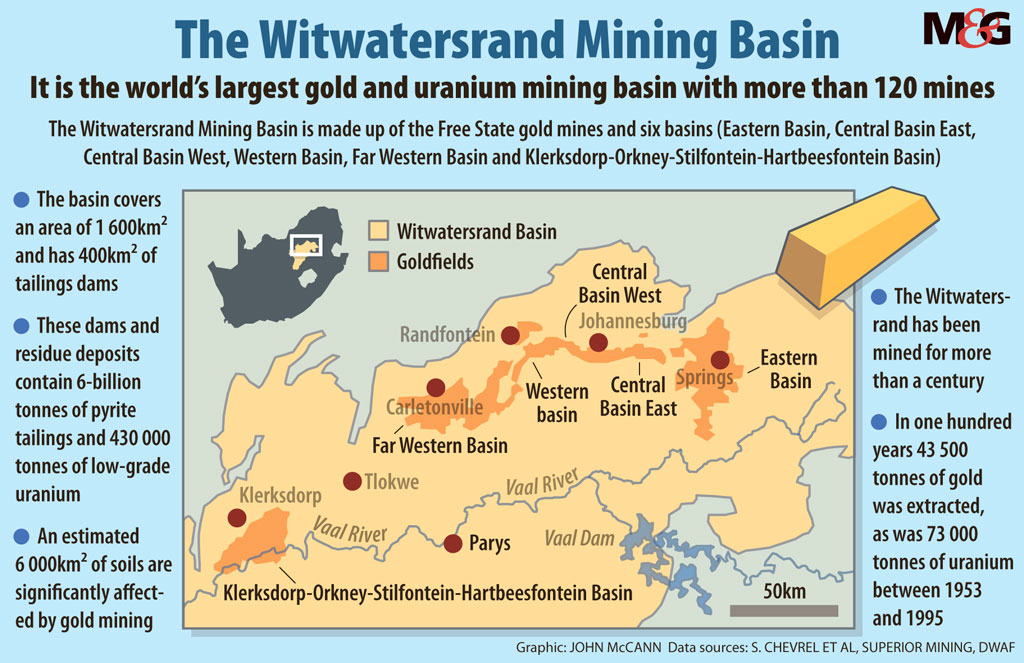

Twelve years ago, the department of water affairs and the National Nuclear Regulations classified 36 radiological hotspots in the Wonderfonteinspruit catchment — once the richest gold mining area in the world — including dams, wetlands and canals that contained elevated levels of cadmium, cobalt, copper, zinc, arsenic and uranium.

Fifteen were ranked category one sites, “where there is no reason to delay immediate action”, with Lancaster Dam rated the most urgent site for remediation.

Mintails, they stated, had allowed acutely toxic water and slimes from dams to migrate to the wetlands downstream of Lancaster Dam.

[related_posts_sc article_id=”230001″]

Nothing has been done to remove the potential risks, says Liefferink.

Gift Mbesi, who lives in Khutsong, shakes his head in despair at Lancaster Dam. “The people who are doing this [mining] know they are not going to be here with their families. They’ve taken the profits where it’s safe to live and treat our country as a dumping site,” he says. “People are growing food with this contaminated soil and their livestock are feeding on this grass that contains chemicals and are drinking this toxic water.”

Two years ago, the FSE, represented by the Legal Resources Centre, filed a landmark lawsuit, requesting the high court in Pretoria to order the ministers of three departments — mineral resources and energy, water and sanitation and environmental affairs — as well as Mogale City local municipality, to hold the directors of Mintails accountable for the ecological degradation and pollution, to hold them delinquent and to call for their deregistration. The action is unopposed.

The ecological damage includes unrehabilitated reclaimed tailings storage facilities, polluted and toxic dams, clusters of open pits 30m to 40m deep, partially reclaimed tailings storage facilities with no mitigation and management measures, and acid-producing stockpiles of waste.

Although the department of mineral resources and the department of water and sanitation have issued the company with pre-directives and directives for noncompliance since 2013, these were not enforced. Both departments did not respond to requests for comment.

Mintails has an unfunded environmental liability of R460-million, and a report from the parliamentary portfolio committee on mineral resources, which conducted oversight visits on its operations in 2018, notes how it had “saved barely R20m for all its responsibilities”.

This refers to the money Mintails was supposed to set aside under the law to pay for environmental rehabilitation. The committee noted how the state will now “inherit these liabilities” after the company was liquidated. “The committee is often confronted by instances of the devastation caused by careless mining where the department says it is a state liability because no one can be found to take responsibility.”

Its report described how the department of mineral resources had allowed Mintails to operate between 2012 and 2018, despite it never having approved the environmental management plans of the mine and had never issued the company with a mining right under the law.

In her founding affidavit, Liefferink says failure to address the pollution will have “catastrophic consequences” for taxpayers, future generations, the natural environment and human health” with the negative effects “externalised to the state, neighbouring mines, financially beleaguered local municipalities and communities characterised by widespread poverty”.

Mintails reclaimed only the profitable sections of the dumps, Liefferink says. She has seen people being baptised in toxic pools and children swimming in them on hot days.

“Certain people have died — the mining area is open and an exceptionally dangerous area to be in,” the affidavit reads. Wetlands have become “potentially radioactive toxic dump lands” and the applicable mining area is now “ecologically dead”.

The FSE has “begged” government departments to take action, “tirelessly submitting reports” and conducting “well over 1 000” site inspections with the organs of state and other key stakeholders, to no avail.

In July last year, a report by the Mind the Gap consortium described how the bankruptcy case of Mintails “provides an example of irresponsible disengagement by investors, leaving the state and local communities around the mines with the burden of uncovered post-mining environmental rehabilitation costs”.

Johan Moolman, who resigned as the chief executive of Mintails South Africa in 2018, says Mintails was put into liquidation in August 2018. “If the company is in liquidation nothing is going to happen and there aren’t sufficient rehabilitation trust funds, as everyone knows.

“There is a transaction possibly happening with [gold producers] Pan African Resources to buy all the dumps, which will address most of the environmental liabilities, including most of the water issues, including Lancaster Dam,” he says, adding there was another application for mining rights for the open pits. “We’re hoping that the [Pan African Resources] transaction gets finalised because then at least the environment will be looked after.”

He says the liquidators had not protected the company’s assets. “As soon as they took security away, the zama zamas came in and destroyed all the plants … the zama zamas came in and cut it up with blowtorches and ankle grinders and carted everything away. So, there are no assets to sell.”

About 30km away in Riverlea, resident Cedric Ortell shows the damage left by the liquidated Central Rand Gold — a gaping unrehabilitated open pit next to the George Harrison Park heritage site and alongside the TC Esterhuysen primary school.

The site is teeming with artisanal miners. “This was a historical site for Riverlea, but it’s ruined,” he says. “Our gold has travelled the world, but we have not benefited.”

An artisanal miner descends stairs littered with old clothing and batteries from headlamps, to a shaft.

“This is how we are putting our kids through school. There’s still gold that we are finding, even if it’s not safe,” he says.

[/membership]