Tiny steps: Nelson Mandela and FW de Klerk make opening press statements during the first talks between the National Party government and the ANC.(Photo by © Louise Gubb/CORBIS SABA/Corbis via Getty Images)

Frederik Willem de Klerk, apartheid’s last president who died in Cape Town on Wednesday from cancer at the age of 85, was a joint winner of the Nobel peace prize in 1993 along with Nelson Mandela.

De Klerk unbanned the ANC and other anti-apartheid political formations and led the National Party, which had ruled South African since 1948, into the negotiations process and the transition to democracy in 1994.

De Klerk, who had served as the apartheid state president from 1989, survived the transition to democracy unscathed, acting as second deputy president in Mandela’s government of national unity from 1994 until 1996.

He was a key figure in the implementation of Bantu education in his role as education minister under then state president PW Botha.

De Klerk was forced by international isolation and the impending violent overthrow of his regime into unbanning the ANC and other liberation movements, releasing political prisoners and entering into negotiations.

Despite helping end apartheid, De Klerk remained an apologist for the policy, declared a crime against humanity by the United Nations general assembly in 1973, and for the brutality and killings that took place in its defence — and under his watch as head of the then State Security Council (SSC).

De Klerk also failed to take responsibility for the murders, torture and hit squad operations that were authorised and carried out under his leadership, instead claiming ignorance of the excesses of an alleged few rogue elements in the apartheid security forces.

In his submission to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), De Klerk said: “The National Party is prepared to accept responsibility for the policies that it adopted and for the actions taken by its office-bearers in the implementation of those policies.

“It is, however, not prepared to accept responsibility for the criminal actions of a handful of operatives of the security forces of which the party was not aware and which it never would have condoned.”

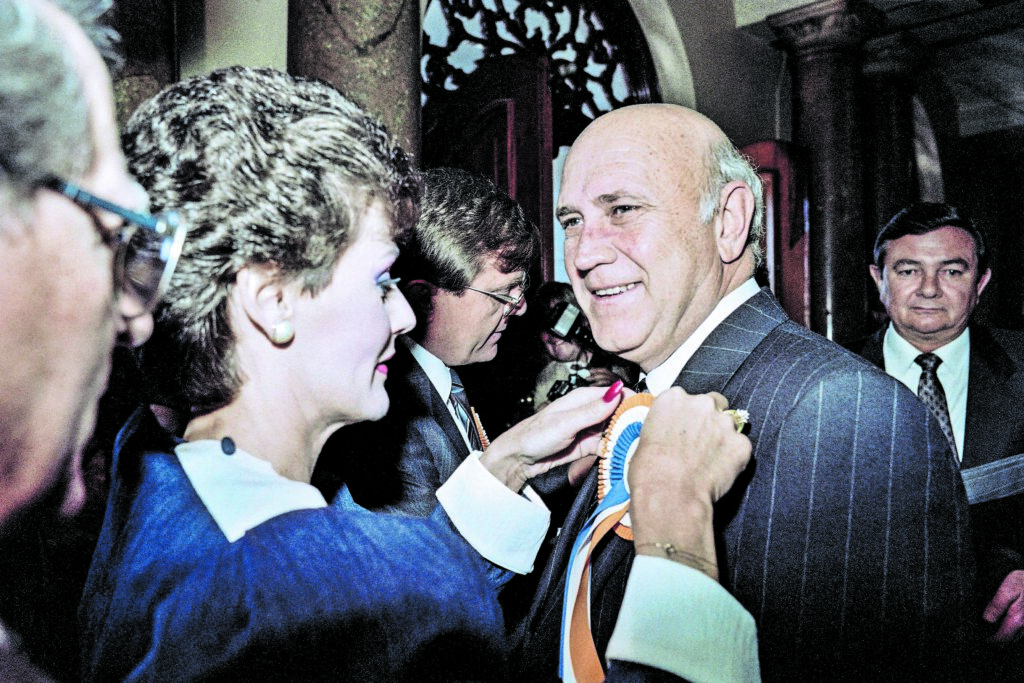

A supporter pins a party badge on De Klerk at the NP federal congress in June 1989, which discussed the five-year reform plan on easing apartheid while mantaining the principle of racial segregation. (Photo by WALTER DHLADHLA/AFP via Getty Images)

A supporter pins a party badge on De Klerk at the NP federal congress in June 1989, which discussed the five-year reform plan on easing apartheid while mantaining the principle of racial segregation. (Photo by WALTER DHLADHLA/AFP via Getty Images)

Days before the publication of the report of the TRC in 1998, De Klerk went to court to stop it publishing findings that he knew that police had bombed the South African Council of Churches offices in 1988, but had failed to disclose this.

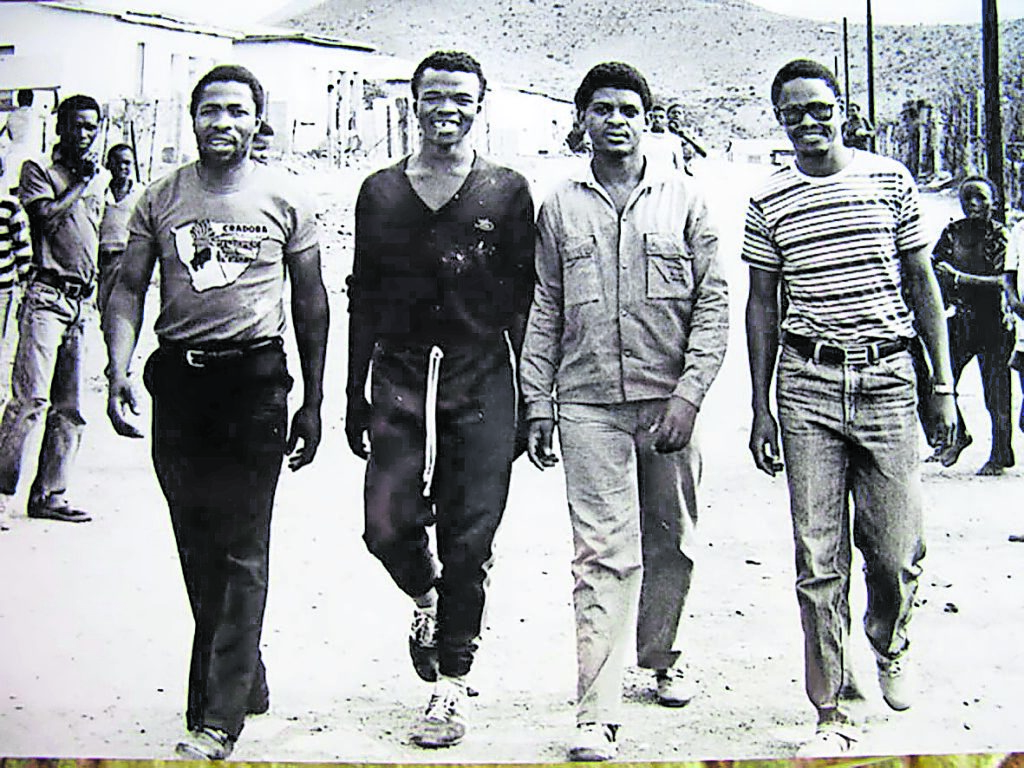

De Klerk’s death means that attempts by the families of the Cradock Four — Matthew Goniwe, Fort Calata, Sparrow Mkhonto and Sicelo Mhlauli — who were murdered in June 1985, to have him charged over the killings for his role in the State Security Council decisions, have died along with him.

It also means that De Klerk’s role in the “deal” between the ANC and former apartheid era-leaders not to prosecute cases stemming from the TRC, which the FW De Klerk Foundation alluded to in an editorial on its website in July, may also never be ventilated.

In the editorial the foundation said: “Because of an informal agreement between the ANC leadership and former operatives of the pre-1994 government, the NPA [National Prosecuting Authority] suspended its prosecutions of apartheid era crimes.”

The editorial was written in response to attempts to have TRC cases brought before court and calls for a judicial inquiry into why they have been stalled for nearly 30 years.

The Cradock Four case was among 20 cases stemming from the TRC, which investigated apartheid era human rights abuses, for which nobody had applied for amnesty and had finally been referred to the NPA after decades of the state failing to act.

Family members of the murdered men and the Foundation for Human Rights went to court earlier this year to force the NPA to provide its record as to why it failed — or refused — to prosecute those responsible for the murders.

De Klerk’s role, allegedly again through the State Security Council, in ordering the operation in October 1993 that resulted in five youngsters — Mzwandile Mfeya, 12, Sandile Yose, 12, twins Samora and Sadat Mpendulo, 16, and Thando Mthembu, 17 — being killed will also never be scrutinised because of his death.

Lukhanyo Calata, Fort Calata’s son, said it was “disappointing” that De Klerk had died before his alleged role in the killings and others was interrogated by the court.

“It is very disappointing because De Klerk was a former president and he knew about the murder of the Cradock Four intimately. The fact that he has never been held accountable or even seen the inside of a courtroom to account for what he did and to explain what he knows is sad,” Calata said.

De Klerk’s death also comes ahead of a promise of a commission of inquiry into the failure of the NPA to prosecute TRC-related cases by Justice Minister Ronald Lamola, at which the “deal”with the ANC would also have come under scrutiny.

“In many ways this [his death] suits the ANC because it means their secrets will continue to be protected. De Klerk had intimated that there was a deal and had threatened to expose it,” Calata said.

Truth denied: Matthew Goniwe (right) and Fort Calata (second from right), two of the Cradock Four, were killed by state security forces in 1985. (Karin Brulliard/The The Washington Post/Getty Images)

Truth denied: Matthew Goniwe (right) and Fort Calata (second from right), two of the Cradock Four, were killed by state security forces in 1985. (Karin Brulliard/The The Washington Post/Getty Images)

The TRC found that the then cabinet and State Security Council were responsible for planning operations that “constituted a systematic pattern of abuse which entailed deliberate planning on the part of the former cabinet, the state security council and the leadership of the military and police”.

It also found that the State Security Council had provided clandestine support to paramilitary groups, including Inkatha, and that “accountability for the human rights violations that flowed from the establishment of the hit squad lay with 22 people from the SSC, military intelligence, Inkatha …”

The TRC also concluded that members of the State Security Council knew that their actions and instructions were illegal and would result in people being killed and injured.

It was “struck by the fact”’ that De Klerk, who had denied knowledge of and responsibility for the hit squad killings in his appearances at the TRC, failed to ask questions of his colleagues about the unlawful operations.

Howard Varney, part of the team representing the Calata family, said De Klerk had been a suspect in the Cradock Four case.

“He claimed at the TRC that apartheid atrocities were just the work of a few bad eggs and that cabinet was blameless. He lied in making this submission.

“He goes to the grave without answering for his role in apartheid era crimes,” Varney said.

[/membership]