Shelter: Violet Maliwa and her husband opened their home to women who live alone. Photos: Delwyn Verasamy

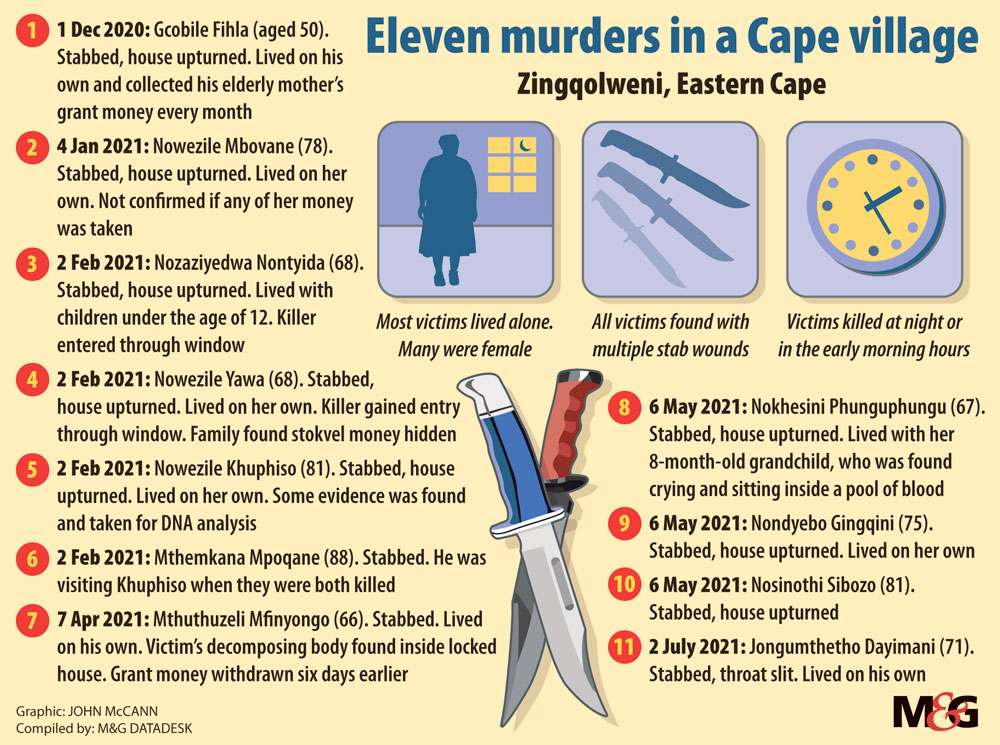

Six men accused in the murders of 11 older people from Zingqolweni village in Cacadu in the Eastern Cape have been arrested, months after the chain of deaths stoked fears of a serial killer.

On average, one victim was robbed and killed almost every month between 1 December 2020 and July last year, leading to the area being named “the village of death”. The arrests come after several reports of house-breaking incidents last month.

According to a villager who asked not to be named, one of the suspects was arrested for the house breakings and later confessed that he and five other men were behind the murders that left older women in the village traumatised, with some fleeing for their lives.

Prior to the arrests, Eastern Cape police had been silent about their investigation into the murders, leaving villagers in the dark for months after the body of the last victim was found last July.

Most of those killed were over the age of 70. Some were stabbed, while others had their throats slit and their homes ransacked. In seven of the cases, the victims lived alone.

Life in the village has now taken an even darker turn, as seven young men aged between 21 and 27, who were allegedly accused of being behind the killings, have themselves been murdered. They were allegedly set alight, with two of them hanged in a nearby forest.

In the village of Zingqolweni homes are scattered far from each other

In the village of Zingqolweni homes are scattered far from each other

Twelve men were charged for the seven murders of the young men but were granted bail last December.

“What other choice was there? The police had ignored the tip-offs that they were given about some of those boys but nothing was done and people were dying,” said a resident, who asked not to be named.

This has effectively brought the number of murders to an astonishing 18 in just under a year.

Inside the ‘village of death’

It was 2 February 2021, two hours after midnight in Zingqolweni, 20km from the Lady Frere police station. Shortly, cellphones would start ringing to wake the villagers and inform families that four women had been murdered.

The bodies of two next-door neighbours, Nozaziyedwa Nontyida and Nowezile Yawa, were the first to be found that night. Six hours later, less than 5km away, 81-year-old Nowezile Khuphiso’s body was discovered in a pool of blood inside her rondavel. Her clothes were scattered on the floor, the small room was ransacked and furniture upturned. In the same rondavel, 88-year-old Mthemkana Mpoqane was discovered lying on his back in the centre of his home with multiple stab wounds, a few metres from the door.

Clothing found inside Khupiso’s rondavel provided the only lead for police.

Four murders, one night

A year after his mother’s brutal murder, Jonguxolo Khuphiso, 59, is still unable to come to terms with the killing. At the time, there were no leads from police. It had been 12 months since they had contacted him, he told the Mail & Guardian recently.

It was only this February that police returned to the village, after almost seven months of silence following the last murder reported in July 2021.

When the M&G visits, Jonguxolo has just been called home by his wife from where he was helping a neighbour with renovations around the yard. Dressed in a blue work suit, hands still covered with dirt, and with sweat streaming down his forehead, Jonguxolo catches his breath as he washes his hands before sitting outside on a black-and-grey chair from his kitchen set.

With a tree offering shade from the unrelenting sun, he recalls the morning that changed his life. It started with a 3am phone call from his sister-in-law.

“She asked if we had heard about the people that had been killed. I tried to call my mother and her phone rang until it went to voicemail. I just told myself that she was probably still sleeping.”

He lives five minutes away from his mother’s house, with his wife, four children and his sickly mother-in-law.

Photo Delwyn Verasamy

Photo Delwyn Verasamy

Jonguxolo said he woke up with his wife and they drove to 68-year-old Nozaziyedwa Nontyida’s house. She would be the first of four murder victims to be discovered. Family members said Nontyida’s body was found a few metres from her bed in the rondavel she shared with her grandchildren, all under the age of 12. She was lying in a pool of blood, with nine stab wounds to her body.

Nontyida used to wake her grandchildren regularly at about midnight for them to urinate in a bucket kept in the room. When this ritual did not happen, a 12-year-old grandchild woke up on his own around 2am and called out for his grandmother to switch on the light.

The confused boy then got out of bed, and tried to wake his grandmother, but she did not respond. He then looked for Nontyida’s phone and called his mother, who lived in Cape Town, to inform her that he was scared because uMakhulu was not waking up. Nontyida’s distraught daughter then called her relative, Nosakhele Nontyida, to go and check on her mother and children.

“We decided to go check on her friend who lived on her own and to inform her about what had happened,” said Nosakhele Nontyida, recalling walking in the dark feeling bewildered.

Holding onto a little hope

Jonguxolo remembers that while heading to Nontyida’s home, he held hope that he would find his mother among the people who were gathering there. He kept trying to phone her but no one picked up his call.

Hope began to disappear when no one had seen his mother.

On arrival at Nontyida’s pink rondavel, there was a hive of activity with police officers and forensic investigators gathering evidence and taking photos of the crime scene.

During the buzz one observer heard a piercing cry. Next door, Nontyida’s neighbour and friend, 68-year-old Nowezile Yawa, had been found in a pool of blood near the door, with multiple stab wounds to her upper body.

The killer had gained entry through the windows of both rondavels.

Nosinothi Sibhozo and her sister-in-law Nonyebo Gingqini were murdered in the pink-walled rondavel where they lived.

Nosinothi Sibhozo and her sister-in-law Nonyebo Gingqini were murdered in the pink-walled rondavel where they lived.

By 8am a meeting had been called to inform the villagers of the two murders. But it was interrupted by news that two more bodies had been found. One of them was Jonguxolo’s mother.

“It was like a horrible film.To this day, I try to block it out but there are moments when it creeps up on me. I don’t know how I’ll ever forget it,” an emotional Jonguxolo says.

He rubs his hands and then his eyes as he recounts the moment he found his mother’s body.

“As I entered, the first body I saw was that of [Mthemkana] Mpoqane, who sometimes visited my mother. I wasn’t focused on him, my concern was my mother, whom we found lying on the floor beside the bed. Looking at the place, I could see that a struggle had ensued because the bed had been moved to the centre of her house. Her body was just lying there with a stab wound on her chest and so was Mpoqane.”

Holding back his tears, Jonguxolo adds: “I didn’t know whether to cry or what. I was confused, I was really confused because she never had quarrels with anyone. I didn’t know that she would suddenly be gone because someone has killed her. It’s painful, it’s very painful.”

A denim jacket found hanging on a nail, a black woolen glove and a globe holder that Jonguxolo and other family members had never seen before were taken by forensic investigators for DNA analysis.

Connecting the dots

On 1 December 2020, Gcobile Fihla, 50, was found dead with multiple stab wounds. Fihla was meant to collect his mother’s governmental older person’s grant that day.

On 4 January 2021, 78-year-old Nowezile Mbovane was killed in a similar fashion as Fihla.

It was the 2 February 2021 multiple murders that escalated the alarm for the villagers. These victims, too, were killed in a similar way.

Older people receive their social grant during the first few days of each month. All the murders happened during the first week of the month. Except for the first victim, everyone was older than 65 and receiving pensions. And all the homes were ransacked as if the attacker was looking for something.

“We think the killer was after money because where the murders took place, you would find clothes scattered all over as if they were searching for something and things like TVs or phones were not taken,” said Jonguxolo.

But he is not sure if any money was taken from his mother’s house because no one knew where she kept it.

Violet Maliwa, a villager who provided shelter for women who were afraid to sleep on their own, added that “in some instances, they would find the money had been taken and in some instances the money would be there because the deceased hid it where the killer couldn’t find it”.

Although crimes against women and children have been prioritised in the national strategic plan of 2020 to 2030 on gender-based violence and femicide, murders specifically committed against older people who, according to the Older Persons Act, are women aged 60 years and above, and men aged 65 years and above, are not categorised as such.

A researcher from Unisa’s Institute of Social and Health Sciences, Dr Lu-Anne Swart, said eldercide was understudied in South Africa despite the country having one of the highest rates globally.

Between 2002 and 2010, out of 14 678 homicides, the average homicide rate for older people in Johannesburg was 23.1 per 100 000. In 2009, the average eldercide rate increased to 25.4 per 100 000 compared with the global rate of 4.5 per 100 000, said Swart.

She added that data collected from Mpumalanga in 2007 showed that older people were being murdered at a higher rate compared to younger people. Several factors contributed to the killings, including “South Africa’s violent context”.

“They are in isolation, they can’t protect themselves. Their vulnerability makes them easy targets. They are made more vulnerable if they live in poverty,” Swart added.

Villagers not reassured by resumed investigation

None of the families of the 11 older people who were killed in Zingqolweni from December 2020 to July last year had heard from the police since the last murder. Then out of the blue in mid-February the police showed up to ask further questions.

“The way I see it, they are somehow blaming us for not assisting them but we too are looking at them for help. We don’t know what to think because we lost loved ones and are expecting them to help us find the killer,” Nosakhele Nontyida said.

Jonguxolo says that he has lost faith in the system and is beginning to accept that his mother’s killer will never face justice.

Until this week, neither national nor provincial police had responded to questions from the M&G since last December.

The grave of Nosinothi Sibhozo shows she was killed on 6 May 2021.

The grave of Nosinothi Sibhozo shows she was killed on 6 May 2021.

All that Eastern Cape police spokesperson Colonel Priscilla Naidu said was that the murders of older people, especially women, were prevalent in rural areas and police had embarked on awareness campaigns to educate and inform people about the necessary precautions they could take to safeguard themselves.

Naidu added that older people living on their own, as well as the distance between the homes, were some of the factors that made them vulnerable to criminals.

Zingqolweni older women displaced

After the 2 February 2021 killings with no arrests being made, it became clear to the older women of Zingqolweni that they were on their own. Some began sleeping in groups or fleeing from the village to as far afield as Cape Town and Johannesburg to live with their children.

Sisters Miliswa Nduku, 68, and Novumile Hlaliso, 81, had never imagined that the once safe village where they had spent all their lives, playing bare-breasted and barefoot as young girls, would be the place they feared the most.

In the early hours of one April morning in 2021, while they were holding their now-regular vigil, guarding and listening for any suspicious sound or movement, Nduku saw an unknown person flashing a light towards them through the window. She screamed out of fear and woke up Hlaliso, who blew into a whistle, which all residents had been given.

Although they cannot be certain that it was the suspected serial killer at their window, they took it as a sign that if they remained in the village, they would be next. They packed some of their belongings that day and moved in with their older sister at Maqhashu village, 8km away.

“It was not an easy decision to make but we had spent months without any sleep because we were afraid that we too could be killed in our sleep,” said Nduku, sitting on the floor of their two-roomed house.

“They wanted our blood. We would wake up finding people dead, and that was what drove us to Maqhashu,” Hlaliso said.

Six months later they had to return to their home because Hlaliso had broken her leg. She now spends her days on a mattress, hoping to heal despite not being able to afford the trips for her check-up at the hospital. Each trip costs R800.

‘We waited for the killer to come for us’

Others, like Maliwa and her husband, who suffered a stroke in June 2020, had no choice but to remain in the village. So she opened her home as a refuge to other women and children.

Up to 20 adults and children would huddle up inside the rondavel that is furnished with two large beds, a fridge and a table with a TV on it.

Sitting next to her husband, whose legs are covered with a fleece blanket and leaning onto a stick for support, Maliwa explains that staying was the only option.

“Where else would I go with my husband in this condition? We waited for the killer to come for us,” she said from her seat on one of the beds, covered in a blue silk sheet.

Even though he is unable to walk, Kittiboy Maliwa, 77, volunteers to stay up at night, guarding the women and children as they sleep.

He felt he had to be brave, especially for his wife, who had become more than just his nurse since he had the stroke, but was now also a safety net for her vulnerable neighbours.

Nosakhele Nontyida says she felt the police were blaming villagers.

Nosakhele Nontyida says she felt the police were blaming villagers.

“I couldn’t sit by and watch them go through that alone. The least I could do was to stay up so they could get some rest.”

Still disturbed by the violence and death that they witnessed almost every month for seven months, Kittiboy consoled his wife, who had seen most of the bodies and relayed to him what she had seen, an experience that Maliwa reluctantly agreed to share with the M&G.

“You need to tell them, it will help you to talk about it,” encouraged Kittiboy.

Holding each other they both cried as Maliwa spoke about the ordeal.

“This is why I didn’t want to talk about this. I have never spoken about it. We were very disturbed by these murders. These were our people. For months we didn’t get any sleep and took turns to guard those who were sleeping and whoever was up, would carry a spear in case the serial killer attacked.”

“We didn’t know whether the killer worked alone or in a group so Tata would also ask us to give him his spear and tell us that if one of the attackers dared to enter, he would make sure that never get out of here alive.”

People who suspect that an older person is being abused can call the gender-based violence command centre at 0800 428 428 or send a USSD-supported “please call me” to *120*7867#. They could also call the police on 08600 10111.

This reporting was supported by the International Women’s Media Foundation’s Gender Justice Reporting Initiative.

[/membership]