African National Congress Women's League (ANCWL) members seen singing during Winnie Mandela's funeral at Orlando Stadium in Soweto. ((Photo by Bongani Siziba/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images)

The once-powerful ANC Women’s League, whose national executive committee (NEC) has been disbanded, sealed its own demise, according to political analysts.

Professor Susan Booysen said the league’s troubles were self-inflicted and political analyst Sanusha Naidu raised questions of irregularity regarding financial and nonfinancial matters, as well as questions about leadership.

Governance, structural deficiency and finances have been flagged as areas where the league has been found wanting. In February, the league’s secretary general, Meokgo Matuba, delivered a damning report showing that it had no functioning branches, regions and provincial structures in most provinces.

Matuba is said to have highlighted that five of the provincial secretaries were not working full-time and had instead been deployed to the government. Insiders said the national working committee heard how branch audits on the league’s readiness for a conference were moving at a snail’s pace because the branches were dysfunctional.

Matuba said the mandates of the league’s structures had expired, that there was a slow intake of new members and many of its branches failed to reach quorum when they met.

“We don’t have an organisation throughout the country. Comrades are working but the problem is the good standing, the branches, the strength and vibrancy of the organisation. That mandate we want from the PEC [provincial executive committees] and RTT [regional task teams],” she said. “There is no organisation in Northern Cape, we need to pull out and find comrades there. In Mpumalanga, there don’t have structures in good standing; we don’t even have structures that are acting. In KwaZulu-Natal we have extended their mandate and the secretary continues to work.”

Yet some believe the recent NEC decisions were aimed at destroying it before the ANC elective conference in December. The league’s president, Bathabile Dlamini, has said the disbandment was part of a greater mission to destroy the league.

Booysen said that, unlike the ANC Youth League, which was dealt a fatal blow by its mother body, the women’s league’s troubles were of its own making.

It’s a different kind of death from the youth league. In the youth league, there was activism, there was the fervour and it disintegrated after Julius Malema, because the only way to get rid of it was to exorcise it. It was killed off by the main body. People were expelled and it was never able to resuscitate itself. The women’s league’s [death] is self-inflicted because not much has been happening,” she said.

“I don’t see any signal that there is life in the structure; that it is making a difference in women’s rights. If you look at it during a trying time [Covid-19 pandemic], where we have massive unemployment and hunger, this would have been an opportunity, if not a calling, to step in and make sure they make a difference. They didn’t see that as a priority.”

Naidu said the women’s league had been an important dynamic in the ANC but said she does not think this has been lost completely.

“What is interesting is that [the league] has become fictionalised … in the party and in the fictionalisation you end up in the situation where the league hasn’t been performing well. There have been questions of irregularity, whether financial or nonfinancial, and questions of leadership. You are beginning to see these eruptions and kind of segregation of association coming more starkly and explicitly now than it did previously,” she said.

Naidu said the women’s league had remained a central figure in ANC life even when abandoning its principles of standing by women — as seen in the lead up to the rape trial of former president Jacob Zuma.

The league was largely successful in galvanising women during the fight for liberation but she questioned whether the league had evolved with the time.

“To a large extent, I think the league retained a vertical and pedantic approach to what is gender balance; how do we deal with gender parity and integration. I don’t think the [women’s] league — if you cross-compare with the youth league — actually understood that they can be the voice of young people … who are much more open and critical of the government. The successes of the women’s league have to be measured on where society is going and where the younger voices are,” Naidu said.

The political analysts argued that in its steadfastness to support Zuma, the women’s league accepted being allowed at the door but not necessarily in the room when some of the policy issues were addressed.

Although the league maintained its public activism on gender representation in the ANC and the government, Booysen said it lacked the appetite to push for more and instead settled with a measly victory of a women’s ministry.

In 2009, Zuma created a ministry to focus on women, youth, children and people with disabilities. This was seen by some as Zuma’s payback to the league for its support during his uphill battle for the ANC presidency. The ministry has been held by women’s league leaders, including Dlamini.

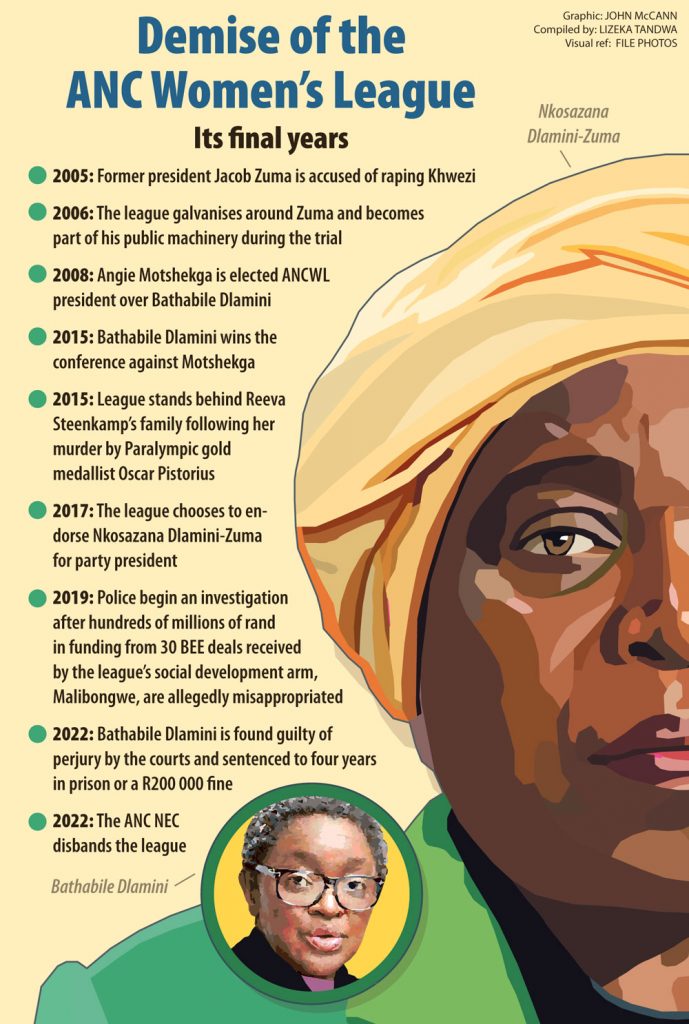

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)“They took that as an ultimate victory,” said Booysen. “They didn’t take that as just a little part of a victory. It was a sign for them that they had arrived. They were distracted and did not see that as a little starting point.”

Booysens has also put the downfall of the league at Dlamini’s feet. She argues that Dlamini, who was elected its president in 2015, failed to lead from the front. “She doesn’t have the stature, credibility and reputation … She was preoccupied by positions for a number of years and that type of leadership has absolutely not been forthcoming.”

But Naidu believes Dlamini still has considerable support and the disbandment of the league’s NEC might have implications for Cyril Ramaphosa in his bid for a second term as president of the ANC.

“The question in the minds of those who are feeling aggrieved by the decision is: is it because you genuinely believe there is a governance crisis and therefore disbanding is the best solution or is it because you are in an elective year? The timing and optics are really important in this context. The impression is that there is a bigger set of political interests at pla. Disbanding the league may not necessarily translate into what they [Ramaphosa’s faction] have engineered when the branches go to elective conferences.”

Dlamini believes her problems with the law started when she became vocal about who should lead the ANC prior to the party’s 2017 Nasrec election conference.

“I said to comrades, let’s have a meeting of all women in ANC and agree on who should lead us and then we will all move forward and we will support those proposed. This is where my problems started. I said we must do that because of past experience.

“In Mafikeng we turned against Winnie [Madikizela-Mandela] and women were used to turn against women. In Polokwane we said officials are not a structure so you don’t need zebra [50/50 leadership on a gender basis]. In Nasrec we took a decision to support NDZ [Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma], Jessie Duarte and Maite [Nkoana-Mashabane] and we never went out to talk to other structures.”

[/membership]