Kusile power station.

Eskom is the leading contender to win the newsmaker of the year award. At the current rate, the power utility may even need to have its own special category for notoriety.

But the failures at Megawatt Park reflect more than just ailing power stations, scarce diesel or even sabotage. They tell a story of our past, and the dilemmas of public policy and teach us what is required to become a successful nation.

There’s no gainsaying that Eskom was a catalyst in the growth of our manufacturing sector. Established in 1923, the company powered the expansion of the South African economy beyond the mining industry into the secondary sector. The lack of imports, caused by the outbreak of World War II, added impetus to the growth. The country had to be self-sufficient.

By the 1950s, the importance of Eskom went beyond creating commercial success. It was a matter of national pride for an emerging ruling elite that, although descendants from Europe, had come to regard themselves as natives of the land, Afrikaners. And they were determined to disprove their historical rivals, the English, that they were not uncouth, but too were “civilised” and could lead a modern economy.

By the early 1970s, the manufacturing sector had ballooned to a point where the exclusion of Africans from skilled work threatened further growth. The available pool of white workers just could not meet the demand for skills in the ever-growing manufacturing sector. Job reservation began to be relaxed.

The expansion of South Africa’s manufacturing sector, however, was not simply an illustration of the centrality of energy in economic growth. It also underscored the importance of strategic state intervention. There was a reason the state took the initiative to set up a power-producing plant. It knew that only affordable electricity could catalyse industrialisation.

Eskom did not produce for profit; the state used the revenue to cover all the other costs. Manufacturers, as a result, saved on expenses and directed the bulk of their expenditure towards purchasing supplies and employing labour. That’s what accounted for their phenomenal growth.

The significance of affordable electricity did not decline with the shift in political power. In fact, the demand multiplied. Provision of electricity was extended to many African households, which had been denied by the unkind apartheid government.

That’s what the Union and apartheid governments had done as well — electrifying newly built homes in the white community, which had been dubbed a “poor white” problem in the early 1900s.

The expectation of a better life under a democratic order also increased the demand for jobs. This meant that companies not only had to remain operational but more were needed to open up for business.

Companies not only provided livelihoods for their employees but also revenue for the newly democratised state to expand its offering of social services. This explains the prioritisation of the South African Revenue Service becoming efficient. The success of the post-apartheid state rested on its ability to collect revenue to meet its social demands.

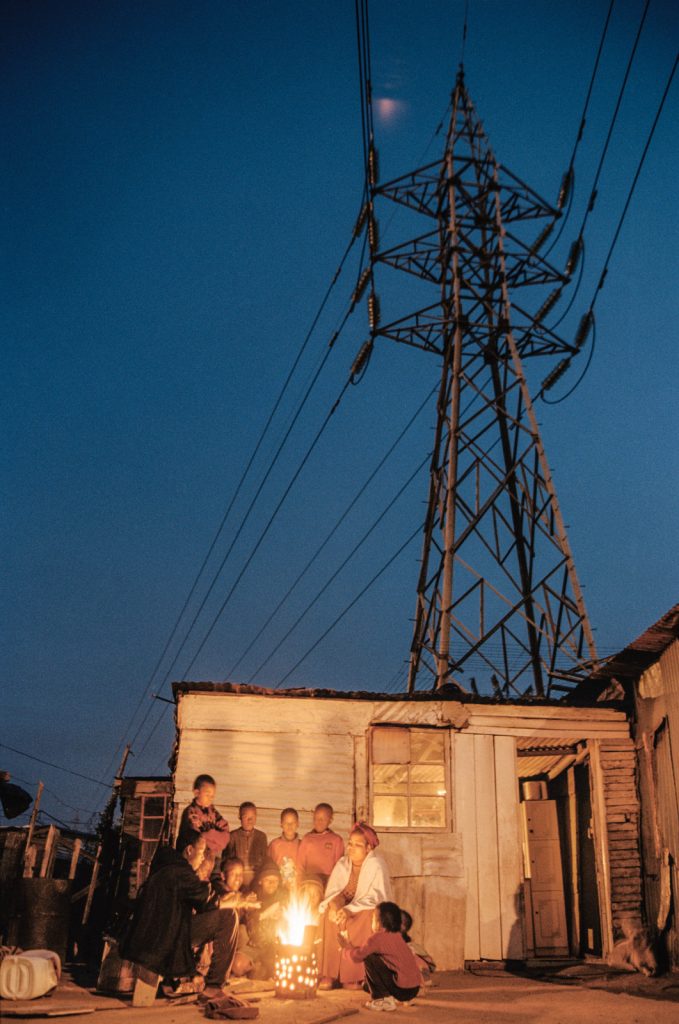

A family who live in a squatter shack in Mbekweni Township near Paarl, keep warm on a cold winter’s evening around an outside fire. Their house has no electricity, although it is overshadowed by huge electric pylons. (Photo by Gideon Mendel/Corbis via Getty Images)

A family who live in a squatter shack in Mbekweni Township near Paarl, keep warm on a cold winter’s evening around an outside fire. Their house has no electricity, although it is overshadowed by huge electric pylons. (Photo by Gideon Mendel/Corbis via Getty Images)

The scale of that revenue depended on the size of the economy, which, in turn, was determined by the availability and affordability of electricity. That’s why Eskom executives advised the government to invest in infrastructure. The existing one was ageing and the increasing demand required more stations to be built.

The urgency for more investment wasn’t readily apparent to the new governing party. All seemed fine. Lights switched on every day and the newly built houses were electrified. They provided evidence for the ANC to highlight their justification for being in power. This was exactly the reason why they were not persuaded by Eskom executives to spend money building new infrastructure.

There were many other pressing social needs that required money. Taking some of that money towards Eskom raised the risk of denying expenditure on the obvious, urgent needs. They ignored Eskom in the hope that their warning was not real or would not materialise.

With time, however, the Eskom executives were proven right. Electricity shortages started in the second half of the 2000s. It was only then when the problem materialised, that the government invested in two new plants, Kusile and Medupi. Commissioned in 2007, the plants were scheduled to start operating seven years later.

In the meantime, load-shedding got worse and worse news followed: the power plants under construction suffered from defects in design, delaying their opening to later in ??2024. And other power stations could not be repaired immediately, especially because there was inadequate money for repairs to dilapidated stations.

Actually, Eskom was beginning to drown under the weight of debt amounting to billions of rand. The problem of debt was partly self-created. Municipalities, for instance, which buy electricity from Eskom and distribute it to households to generate revenue for themselves, were not paying the company. Illegal connections also robbed Eskom of revenue.

Politicians were reluctant to cut off the supply to municipalities or clamp down on illegal connections. Doing so was not the better life they promised. There was likely to be a backlash — a loss of votes for the governing party.

Without an immediate solution to Eskom’s problems, the government had to contend with the uncomfortable question: where can the country get extra electricity to make up for the shortage? Private companies urged the government to allow them to cover the shortage.

That seemed to be an easy solution. The government, too, had contemplated bringing in private producers but was hesitant. Privately generated power would not be affordable and was likely to undercut the revenue that Eskom received from the sale of electricity, especially from the commercial sector.

Apart from the practical problems of cost and loss of revenue, the governing party also suffered from ideological hang-ups. It had committed itself to become a developmental state, with parastatals such as Eskom taking the lead in that transformative endeavour.

Bringing private companies on board to supply electricity, albeit at a relatively minute scale, smacked of admitting defeat. For them, it had the uncomfortable feeling of the beginning of privatisation. And most of them even resented the word itself, for they considered the ANC “a disciplined force of the left”, which should never concede such developmental functions to private business. To do so was a “betrayal of the revolution”.

Former president Thabo Mbeki had tried to convince his comrades in the early 2000s of the foolishness of dogmatism when running a government. He began to commercialise parastatals, bringing in private partners to buy a stake, thereby injecting the much-needed capital to keep the companies going. He succeeded with Telkom, but the hostility was just too much even for him, who was supposedly a stubborn president, to continue.

A team of experts that Jacob Zuma, Mbeki’s successor, subsequently set up in 2010, led by Riah Phiyega, to look into the state of parastatals came back saying the same thing that Mbeki had said a decade ago: get rid of parastatals that are not providing core services and bring private partners to assist the critical ones that are not coping.

After submitting the report in 2013, Zuma’s government simply sat on it for the next five years of his presidency. Cyril Ramaphosa, who succeeded Zuma as president, dusted off the idea that was first mooted more than 20 years ago — commercialising parastatals — by committing himself to bring in private partners in the unbundling of Eskom.

An unbundled Eskom means the private sector will take over the generation of electricity, and Eskom will remain in charge of transmission and distribution. This promises to free Eskom of its R400 billion or so debt and inject new capital for new infrastructure.

The opposition we heard 22 years ago resurfaced against Ramaphosa. The deterioration of Eskom doesn’t seem to have convinced them that a new course is required. It is abundantly clear to any objective person that Eskom needs an injection of capital, and that can only come from the private sector. Telkom has proven that the commercialisation of parastatals does work.

Ramaphosa doesn’t have the option to retract his promise. Mbeki prevaricated because Eskom still kept the lights on, and the ANC was comfortable with almost 70% electoral support. Ramaphosa doesn’t have the cushion that Mbeki enjoyed. Lights are constantly off, businesses are closing and the pool of the unemployed is increasing every day. And the ANC is threatening to plummet closer to 40% in electoral support.

This may well be the crisis the country needed to wake politicians up from their slumber. The worse things get, the better are prospects of reforms. Sadly, that’s what has largely driven human progress.

Mcebisi Ndletyana is professor of political science at the University of Johannesburg and co-author of a forthcoming book on the centenary history of Fort Hare University.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Mail & Guardian.

[/membership]