Abusive: Ever since 2007, when he was indicted on charges linked to the 1990s arms deal, Jacob Zuma has appeared in court regularly. One such appearance was on 26 May 2021 (above) in the Pietermaritzburg high court where pleaded not guilty to fraud, corruption, racketeering and money-laundering. (Phill Magakoe/Getty Images)

NEWS ANALYSIS

While the government considers what to do after the constitutional court denied it leave to appeal a ruling that Jacob Zuma’s release from prison was unlawful, the former president has insisted that this holds no real consequence for him — and he may well be right.

Zuma’s calculation is less rooted in legal reasoning than in the certainty that the department of correctional services will weigh the political implications when it decides whether he should serve more time.

Because the law, on the other hand, is indifferent to Zuma’s delusions of persecution, attacking the credibility of the judiciary has long been part of his legal strategy.

His lawyers, from Michael Hulley to Dali Mpofu, have played along to a greater or lesser extent while filing interlocutory applications and appeals to the point where a 2009 ruling on the validity of warrants in the arms deal case was raised — wrongly — as authority in his recent bid to pursue criminal charges against President Cyril Ramaphosa, itself another far-flung attempt to further delay the fraud trial.

His indictment for corruption in 2007 was “a political conspiracy”. Last month’s high court ruling that put an end to his private prosecution of Ramaphosa was “bizarre”. And the appellate court ruling in November confirming the high court judgment that his early release from prison was unlawful was “an exercise in cruelty” because it allowed for the possibility of him serving the remainder of his 15-month sentence for contempt.

Judges could be forgiven for making mistakes because they too were human, Zuma said, but here they had played God to divine a law that would make him pay twice for the same offence.

“What is totally unacceptable is for judges to change the law to achieve certain outcomes, depending on the name and identity of who is before them,” his statement read.

“Is it not a version of the death sentence to send a person to a place where it has been independently declared that there are no suitable medical facilities for that particular individual? Should judges play God?”

To appreciate his arrogance, it’s worth remembering that neither the high court nor the supreme court of appeal were given the doctor’s report Arthur Fraser relied on to overrule the medical parole board’s finding that Zuma did not qualify for release because he was not terminally ill.

A redacted version was filed to court, with the rest “scratched out in koki pen”, as Judge Clive Plasket put it. Zuma’s insistence that the information remain classified meant the appellants in the matter — he and the correctional services commissioner — were asking the court to show blind trust, Plasket said, adding: “Review does not work that way.”

The legal argument discernible in Zuma’s reaction to the ruling is that he had already expunged his sentence because he served the remainder on parole, therefore returning him to prison would breach the rule on double jeopardy.

It is a novel reading of the rule, which in its proper sense means an accused cannot be tried twice for substantially the same crime, and which was recently invoked by former French president Nicolas Sarkozy in his appeal to that country’s constitutional council over his conviction for illegal campaign financing.

Jacob Zuma appears in the Pietermaritzburg High Court again on 17 April 2023. (Kim Ludbrook/Getty Images)

Jacob Zuma appears in the Pietermaritzburg High Court again on 17 April 2023. (Kim Ludbrook/Getty Images)

Still, it is understood that the department of correctional services is considering using this as a rationale for deciding that Zuma has expunged his sentence. It perhaps need not go that route, provided the Correctional Services Act deems time spent on parole as time served, even where it was not granted in accordance with the law.

The appellate court allowed for this possibility. Contrary to Zuma’s claims, it invented nothing and merely applied the law to rule his release unlawful and order that he return to prison, then wisely left the remedy and the decision as to what, if anything, remains of the 15-month term, to the commissioner.

There are observers who say it is time to let it go because the contempt case was overwrought and divisive from the outset.

Although the department is still taking legal advice to see if it can do so, its reluctance to return Zuma to prison and run the risk of a repeat of the deadly unrest of two years ago was implicit in its application to the apex court for leave to appeal the ruling. But such a threat is not one of the factors the commissioner can by law take into account.

The “lofty and lonely work” of defending the Constitution and the law, impervious to political rhetoric, falls to the courts, Judge Sisi Khampepe said when imposing the prison sentence for defying an order to appear before the Zondo commission of inquiry into state capture.

Khampepe went on to cite a call from Nelson Mandela to the apex court to “stand on guard not only against direct assault on the principles of the constitution, but against insidious corrosion” — indirectly drawing a contrast between his respect and Zuma’s contempt for the justice system.

Years earlier, in an article in a Canadian journal, her colleague, Judge Johann van der Westhuizen, traced Mandela’s lifelong commitment to the rule of law as central to democracy, from his unbowed submission to the Rivonia trial court, denying nothing despite risking the death penalty, to his obliging testimony to courts later when his executive decisions were taken on review.

Van der Westhuizen cautioned that despite this precedent, a tendency was emerging of “increasing excessive reliance on highly technical points to avoid, delay or frustrate legal proceedings” — in short, Stalingrad as we now know it.

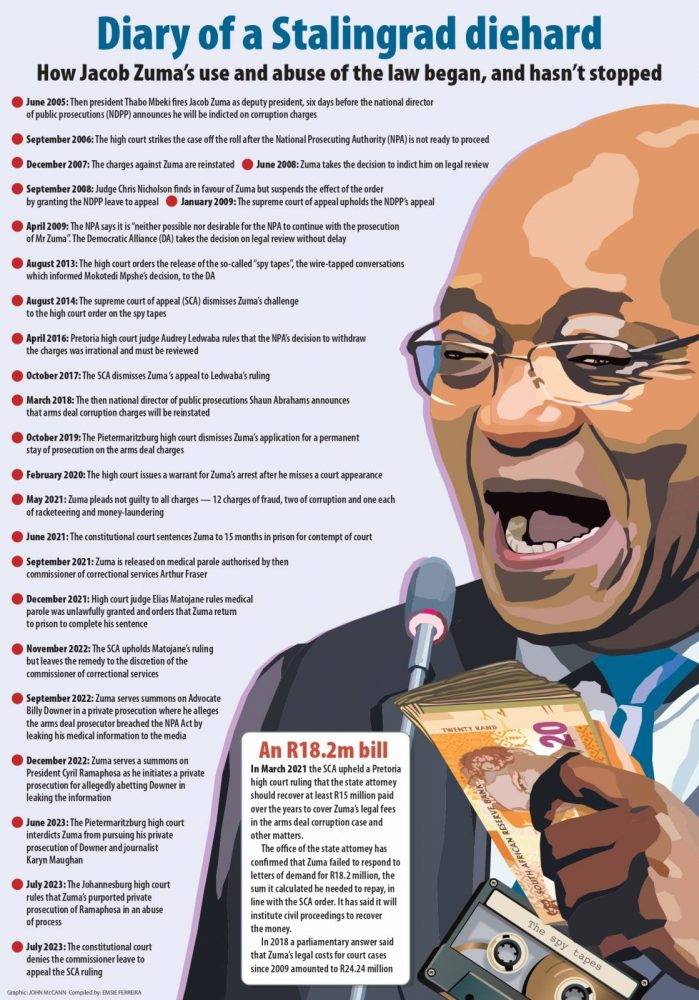

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

“South Africans also often hear criminal accused or their supporters loudly claiming that the charges against them have resulted from a ‘political conspiracy’ and that no court in the country is capable of giving them a fair trial. This is worrying,” he said.

If Stalingrad is now synonymous with Zuma, he did not invent it.

In 2021, when he launched a special plea in terms of section 106(1)(h) of the Criminal Procedure Act to challenge Billy Downer’s standing as prosecutor in the arms deal trial, the relevant case law involved a similar plea brought by Gary Porritt, who had delayed facing trial for fraud, money-laundering and tax evasion in the Tigon scandal for 14 years.

It may not be fair but moneyed defendants have always been able to wage this form of litigation, without much media attention or political menace. The tragedy in Zuma’s case is that the taxpayer has funded most of the farce and that he has abused the safeguards of the rights of an accused to undermine faith in the rule of law.

“I think it has harmed our justice system, particularly people’s perceptions of how the justice system operates,” Judges Matter researcher Mbekezeli Benjamin said.

“Ordinary people — even some lawyers — cannot tell the difference between genuine legal disputes and the nonsense we see dressed up as court applications. That has bred cynicism towards our judiciary.

“That cynicism is weaponised to great effect by those perpetrating the Stalingrad strategy.”

Benjamin noted that others such as suspended public protector Busisiwe Mkhwebane now blithely copy Zuma — her multiple rescission applications refer — but Van der Westhuizen said the subversion of safeguards predated the arms deal saga as lesser officials facing graft charges “pleaded innocent until they believed it” and refused to leave office until the last appeal had been lost.

“For good reason, there is a long legal history behind the presumption of innocence, the right to remain silent and so on. But at some point, even before Zuma, perversion crept in,” Van der Westhuizen said this week.

“They abused all the very safeguards that the law built in for accused persons, often very disempowered people. This can bring up all the philosophical questions as to whether there is a difference between law and justice. For example, it is not unlawful to ask for a postponement but it could be used to undermine the legal process.

“And because it is so political the courts lean over backwards, not because they are concerned about their own power, but because they want to show their fairness and objectivity.”

There is wide consensus in the legal field that Judge Piet Koen’s recusal in the arms deal case — for the stated reason that as the bid to have Downer removed dragged on he had to rule on matters where he had already pronounced on the merits earlier — was an excess of caution and that the constitutional court should not have entertained Zuma’s application for rescission of his contempt sentence.

There are recent indications that the courts are growing reluctant to tolerate Zuma’s excesses, or at least eager to call out his motives and counter his narrative.

In setting aside his private prosecution of Downer, the Pietermaritzburg high court found he had come to court “with unclean hands” because the process was plainly a precursor to seeking Downer’s removal as the arms deal prosecutor in a subsequent application.

And while hearing Ramaphosa’s challenge to Zuma’s bid to charge him, Judge Lebogang Modiba called Mpofu to order for saying he had instructions from his client to complain that being denied extra time to make his argument was “a manifestation of what he calls ‘Zuma’s law’.”

“Those remarks are utterly inappropriate. From the reasoning that I have given in this ruling, clearly there isn’t any new law that is applied only to Mr Zuma. I have demonstrated in my reasoning how he has been accommodated more than the other parties. It is inappropriate for you to be accusing the court of unfairly treating Mr Zuma,” she said.

Serial appearances: On 30 November 2018, Jacob Zuma again appeared in the high court for taking bribes from French arms company Thint. Photo: Rogan Ward/AFP

Serial appearances: On 30 November 2018, Jacob Zuma again appeared in the high court for taking bribes from French arms company Thint. Photo: Rogan Ward/AFP

The rebuke was vitally important, Benjamin said.

“But it’s too little and a bit too late. Lots of reasonable people believe Zuma was jailed for nothing, and that the concourt should’ve granted the rescission. The Stalingrad strategy has dragged the judiciary in matters that are really political more than legal.”

He added that Mpofu has used every court hearing to deliver Zuma’s talking points as soundbites that fit neatly into video clips for social media. (At least one judge has suggested this tendency also stems from his lack of preparedness.)

“All of this is for attacking Zuma’s political enemies rather than raising genuine legal disputes. By entertaining them — as courts should — the courts are dragged into the political arena.”

It is no comfort that other democracies are seeing former leaders attack their courts in similar fashion.

Sarkozy has claimed political persecution. Late Italian prime minister Silvio Berlusconi insisted that he was the prey of politically motivated judges while signing immunity laws to shield himself from prosecution in three interlinked fraud cases. The United Kingdom’s former leader, Boris Johnson, conceded nothing and claimed he was facing partisan revenge for Brexit before he was found guilty of lying to parliament.

Donald Trump’s response to charges stemming from his removal of classified documents from the White House perhaps most closely resembles Zuma’s desperate, dumpster fire populism. “They’re not coming after me, they’re coming after you,” he told supporters after a court appearance in June.

Much has been written about the threat these men pose to the rule of law in democracies far older than South Africa’s. The regression of the US supreme court on abortion and anti-race discrimination rights attests to the ravages of Trump’s politicisation of the judiciary. Here Zuma did not succeed. Former chief justice Mogoeng Mogoeng proved loyal to himself and his faith, not the president.

Unlike Trump, Zuma is not aiming for a political comeback but more modestly playing for time, wagering that at 80 and counting time for pleadings, postponements and eventual appeals, he will not see prison for fraud or state capture either. He may well be right on all three counts.