On notice: International Court of Justice Judge President Joan Donoghue, watched by Israel’s and South Africa’s defence teams, delivers the order on South Africa’s genocide case against Israel on 26 January in The Hague, Netherlands. (Photo by Dursun Aydemir/Anadolu via Getty Images)

South Africa’s delegation to The Hague was protected by an iron curtain of security amid concerns for its safety, after the decision was made to go to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and lodge a case against Israel for its allegedly genocidal intent against the people of Gaza.

The South African delegation of high-ranking government leaders and the legal team had strict security, and also had to use code words to communicate, according to insiders.

Zane Dangor, the director general of the international relations and cooperation department, refused to be drawn on details of the security measures but said there were “clear security threats” that necessitated “the security arrangements that were made”.

Speaking at the ANC’s national executive committee lekgotla this week, President Cyril Ramaphosa said Pretoria was conscious of the fact that there would be systematic fightback campaigns.

“I say this so we are aware of it. There can be little doubt that these forces will do all in their power to prevent South Africa from concluding its case on the merits of the matter in the ICJ,” Ramaphosa said.

The move to approach the ICJ came after several deliberations between the ministry of justice and the department of international relations and cooperation in November.

In the middle of that month, the international relations department announced that it had submitted a joint referral with five other countries — all in the Global South — to the Office of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC) to investigate possible crimes in Palestine in terms of the Rome Statute.

But after the approach to the ICC was made, it was raised in government circles that Israel’s war on Gaza could be considered for violations under the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, which would entail approaching the ICJ.

The justice department’s director general, Doc Mashabane — a former deputy ambassador to the United Nations and an expert in international law — was key to helping formulate the plan for South Africa to approach the ICJ.

Mashabane and Dangor worked with other government officials to approach the state law adviser in the international relations department for advice on whether an application to the ICJ would be permissible. A memorandum was then presented at a special cabinet meeting on 8 December through International Relations Minister Naledi Pandor for approval.

On 29 December, after the cabinet had given its support, the department of international relations announced that South Africa had approached the ICJ.

Main players: International relations director general Zane Dangor (centre), justice department director general Doc Mashabane (right) and Justice Minister Ronald Lamola spearheaded South Africa’s ICJ case.

Main players: International relations director general Zane Dangor (centre), justice department director general Doc Mashabane (right) and Justice Minister Ronald Lamola spearheaded South Africa’s ICJ case.

Dangor said the team discussed two approaches before heading to the ICJ.

It first considered taking the matter to the United Nations General Assembly with the hope that the organ would approach the ICJ.

Dangor said that part of the difficulty with the UN General Assembly was that the case would be treated as a political issue rather than a legal one, adding that the UN would only submit an opinion.

He said the South African team settled on article 9 of the Genocide Convention, which states that disputes relating to the responsibility of a state for genocide be submitted to the court.

“What we were quite aware of with such a contentious approach is that the ICJ is generally used for disputes in most cases around boundaries, water disputes,” Dangor said.

“We knew we were going to get a lot of flack for that because using the ICJ in that way also challenges the notion in the West that they can’t be taken to task in those spaces and that it’s their space to hold others to account. We expected that backlash but we also knew we had a strong case.”

The government had also considered bringing other countries on board to support its case but because of its sensitive nature, it opted to go at it alone, Dangor said.

“We wanted to avoid any challenges or jurisdictional issues that Israel may come up with to make it difficult.”

To illustrate the secret nature of its case during its infancy stages Dangor said the cabinet opted not to release a statement on 9 December.

“We kept it close, we didn’t engage with others [states] but we also knew that because we are going for Article 9 and the provisional measures are important that it’s best to go as South Africa on the provisional measures. If you had to bring other countries on board, jurisdictional issues would have been drawn out. We have now been consulting extensively with them [member states] and we will see a number of countries come in and intervene because now the merits are on the table.”

South Africa’s case was endorsed by several countries, including members of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation and the Arab League which, in the 11th hour, released a statement endorsing Pretoria’s case.

Dangor said it was not disappointing that the Arab League endorsed its case hours before delivering its arguments to the ICJ. The South African government is hoping that those who have the jurisdiction to prosecute Israel under Article 9 of the Genocide Convention — such as Jordan and Egypt — will join the cause, he added.

“We knew the pressures that countries are being put under are enormous. The bigger countries could weather the storm but a lot of the smaller countries were really having to find cover from others,” he said.

“I don’t think it was disappointing, I think it was not surprising given the fact that front line states around Palestine have always been under enormous pressure. The kind of pressures they are being put under we understand and we are appreciative of the fact that they did offer support.”

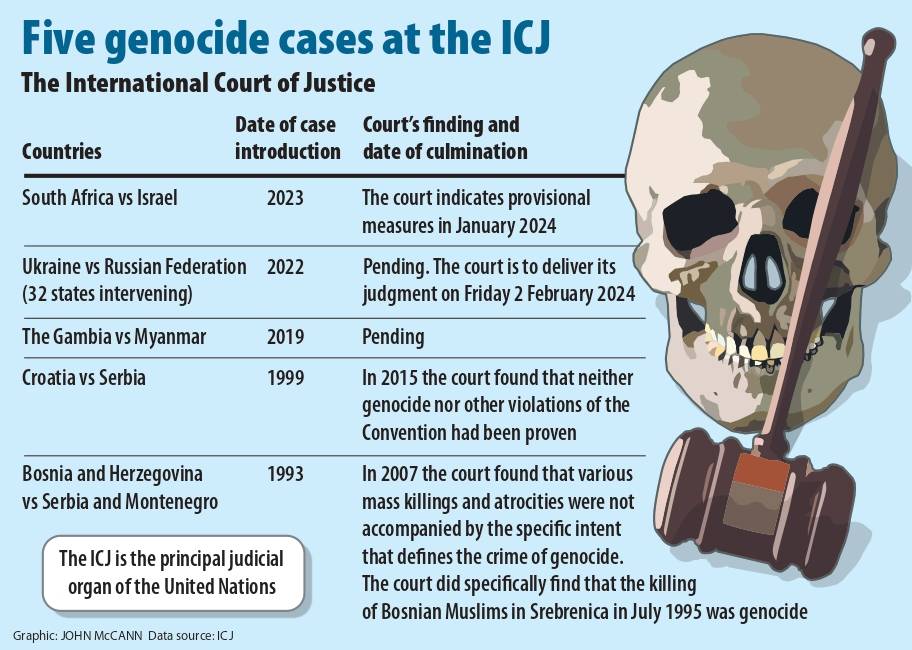

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

Justice Minister Ronald Lamola said matters of diversity to reflect South Africa’s racial composition were factored into the decision about who the government would choose from a pool of legal experts to represent its case at The Hague.

“We wanted experts in the field and the best legal minds in the country irrespective of colour, creed or religion and I think they represented the diversity of the country, the abundance of skills that we have that they can hold their fort against the best in the world. But obviously we needed to mix with some of the international scholars in the United Kingdom who also came in very handy,” Lamola said.

He added that it was part of the legal team’s strategy to have Irish lawyer Blinne Ní Ghrálaigh make her arguments in French.

“The court uses two languages, French and English. She could only communicate to them that we are not being discourteous to them not to use French but it was because of the limited time and the reality that most of our council could only speak English.”

Dangor said the international relations department consulted international law expert John Dugard, who then made his recommendations on the composition of the legal team.

“He then recommended that if we are going to do this given the challenge, these are the people you would need and that is where the Irish lawyer [Ní Ghrálaigh] came on board. Because they have experience in the detail of ICJ processes and the domestic council was brought on board by the department of justice and the presidency. That these are the kind of heads you would need to bring to a case like this,” Dangor said.