Catchment: The White uMfolozi River flows through the Babanango Game Reserve. Photos: Angus Burns/WWF

A black rhino emerges from the thorny thickets in the twilight, two male lions rest in the grasslands and a herd of elephants trumpet through the rolling valleys.

Here, in the wilderness of the 20 000-hectare Babanango Game Reserve in KwaZulu-Natal, are species that last roamed freely on this land 150 years ago.

Since 2022, the reserve near Vryheid and directly inland from St Lucia and the Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park, has been the scene of an ambitious rewilding project, where sustainable conservation, eco-tourism and community development intersect.

In 2018, with the support and facilitation of the nonprofit Conservation Outcomes — the implementation partner of the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) South Africa — the communities of Emcakwini, Esibongweni and KwaNgono reached an agreement to combine their communally owned lands with adjacent private property, owned by international funders, to develop a single contiguous conservation area.

Thriving wilderness: In the last seven years, Babanango Game Reserve has embarked on one of the largest game translocation projects in the country. Photos: Angus Burns/WWF

Thriving wilderness: In the last seven years, Babanango Game Reserve has embarked on one of the largest game translocation projects in the country. Photos: Angus Burns/WWF

“We’ve got privately owned land, community-owned land and government-owned land so that’s conservation in a nutshell in the 21st century,” said Ryan Andraos, the general manager of conservation and operations at Babanango. “It’s very complicated and very difficult … We sit together at tables for hours in meetings and we’re all very committed to making Babanango work.”

For him, Babanango is an “inspiration project” at a time the conservation landscape is filled with sad stories.

The initiative has created more than 210 permanent jobs, 75% of them filled by people from neighbouring areas, including chefs, lodge managers, anti-poaching, security and housekeeping staff. This makes Babanango the largest employer in the area and the second-largest in the local district municipality of Ulundi.

Economic and social benefits to the neighbouring communities are made up of leasehold income from rental agreements that accrue to beneficiaries of the title deeds, as well as preferential employment opportunities.

The African Habitat Conservancy Foundation works with the reserve, the land-owning trusts and others to identify and implement projects that promote enterprise development supporting marginalised people. Some of the benefits include vocational training, drilling boreholes, wi-fi for schools and promoting sustainable grazing practices.

“There is nothing else except this game reserve that is more like a development that people are using as an alternative where they can get benefits from,” said the foundation’s community liaison officer, Thokozani Hlophe. “There’s a high unemployment rate and also the expectation is too high, maybe I would say beyond the capacity of what the game reserve can provide, but it is making the difference for those it can.”

Like its terrain, the road to Babanango’s inception has been long and rocky. By 2015, the land had been virtually emptied of wildlife after decades of unsustainable cattle grazing and unbridled hunting.

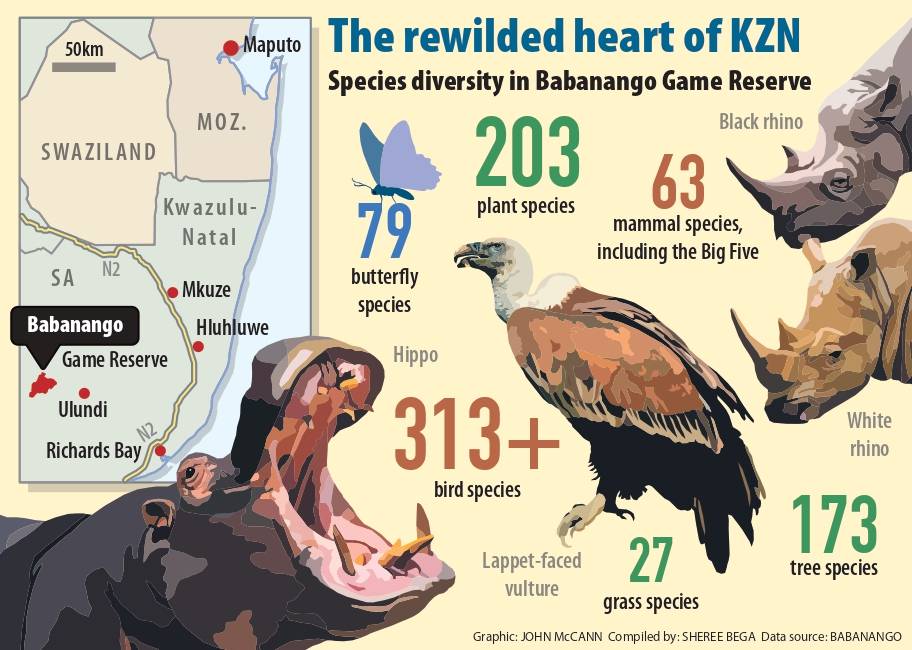

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

In late 2017, German investors Hellmuth and Barbara Weisser started to buy land together with the three local community trusts and laid the groundwork for Babanango. In November last year, it was proclaimed as a provincial nature reserve. The WWF-SA supported it with funding for its nature reserve status application and the drafting of a reserve management plan.

“It was claimed in the early 2000s and once it was given over to communities, unfortunately there were lots of chance-takers who came in quickly to almost take over the ownership of the land,” Andraos said.

Illegal cattle ranchers entered the restituted land, often with cattle stolen from as far as Richards Bay and Pietermaritzburg.

Poaching was prolific. At times, up to 50 men with 200 dogs hunted on the property.

Wild life: Babanango’s game rangers and wildlife monitors and K9 unit members are trained and accommodated at the Roy McAlpine Foundation’s centre, as part of the WWF Black Rhino Range Expansion project. Photos: Angus Burns/WWF

Wild life: Babanango’s game rangers and wildlife monitors and K9 unit members are trained and accommodated at the Roy McAlpine Foundation’s centre, as part of the WWF Black Rhino Range Expansion project. Photos: Angus Burns/WWF

“We [also] had illegal harvesting of trees; indiscriminate cutting of trees for the firewood trade, so they [communities] were really losing this beautiful piece of land that they received from the government 10 to 15 years ago,” Andraos said.

People viewed the creation of a game reserve as an opportunity to “get some value out of their land”, he said. “They grabbed it with both hands, keen to get themselves involved in this potentially Big Five game reserve.

“When we started putting up the fence, we learnt very quickly who our enemies were [the illegal cattle ranchers] and we started very quickly to lose the fence.”

Three years and R13 million later, the fence stayed up and, by the end of 2022, the last of the 2 600 head of cattle was removed. Small cattle-grazing areas have been established on the fringes of the game reserve.

So far, more than 3 000 large mammal species have been reintroduced, including the Big Five, rare antelope such as oribi and klipspringer, and various reptile species.

The reserve is home to a small number of black rhino that were relocated under the WWF’s Black Rhino Range Expansion project. The species is critically endangered.

Initiated by WWF-SA and Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife in 2003, and joined later by the Eastern Cape Tourism and Parks Agency, the project has established 17 new black rhino populations — Babanango was the 15th — on 360 000 hectares of rhino habitat under its custodianship.

Camera traps are revealing the reserve’s little-known treasures such as spotted hyenas, brown hyenas and rare African civets, according to the reserve’s ecologist, Stuart Dunlop.

“We assume that these animals weren’t here but when you start putting camera traps up you start to see that, oh wow, there are porcupines, there are honey badgers here.

“They’ve always been here and at the moment they’re still a little bit sensitive to humans because for a long time they’ve been heavily persecuted in this area,” Dunlop said.

The game reserve falls within one of South Africa’s 22 strategic water source areas and protects the headwaters of the White uMfolozi River. Large tracts of invasive trees, notably wattle, that choke the grasslands and water courses, are being removed from the critical mistbelt grasslands by a mostly female-led ecological restoration team, drawn from surrounding communities.

“All the water emanates from springs on the property,” said Chris Galliers, of Conservation Outcomes. “That is why clearing those aliens is so important to reinvigorate those springs, which all feed into the uMfolozi, and then benefit downstream users, who get more water and cleaner water. The end of the Mfolozi catchment is St Lucia, so it’s an important ecological area drainage system that goes to the coast.”

Safety: Black rhino, a critically endangered species, have been relocated to the Babanango reserve, which also is also good for bird watchers. Photos: Angus Burns/WWF

Safety: Black rhino, a critically endangered species, have been relocated to the Babanango reserve, which also is also good for bird watchers. Photos: Angus Burns/WWF

Weisser, the retired chairperson of the international oil and gas company Marquard and Bahls AG, has ploughed R1 billion into Babanango’s development and a further R100 million annually into its operating costs. “The idea is that at the end of the day, it should be funded by tourists, but we are perhaps two-thirds of the way if I’m cheerful,” he said.

Babanango is “a project of passion” for conserving nature. “It isn’t easy all the time,” Weisser said. “We have three trusts and we have many communities where there are old foes and we have to manage all that and understand it.”

Still, the reward is great, such as the waterfall that started flowing again after the wattle was cleared and the birth of the first lion cubs in the area in 150 years. “That is something that is really an achievement and gives great joy, in spite of all the difficulties we have to overcome.”

The game reserve is steeped in Zulu history and cultural, archaeological and geological features dating back thousands of years.

Galliers said a key objective is to show Babanango as a model for community conservation partnerships.

“There is a lot of important conservation land in the hands of communities … it’s a great opportunity to get communities involved in conservation, because that’s what we really want.”

But beyond their involvement, there are tangible benefits. “That’s the whole thing about the wildlife economy: there are lots of different models and we are trying to see how we maximise the benefits,” Galliers said. “We see the sustainability of these areas as being a direct link to the benefits that flow out of it.”

Conservation land has to compete equally with alternative land use options such as livestock and agriculture. “So, we’re not taking away any option and saying only conservation, excluding everything else. This is saying, choose conservation because it’s actually a competitive land use.

“The benefits — if you just look at the number of jobs created in a reserve like this — are far greater than what you would find if it was just livestock or agriculture.”

Sheree Bega was a guest of WWF South Africa at Babanango Game Reserve.