A male lion on the lookout for prey at the Shamwari Private Game Reserve on November 3, 2022 near the town of Paterson in South Africa's Eastern Cape province. Photo by David Silverman/Getty Images

Africa’s largest carnivore is quietly sliding towards extinction, with its population almost halved in the past 25 years because of habitat loss and fragmentation, the lack of wild prey, persecution and poaching.

For Samantha Nicholson, a senior carnivore scientist at the Endangered Wildlife Trust (EWT), imagining the continent emptied of its lions is unthinkable.

She manages the African Lion Database initiative, which started in 2018 and is endorsed by and carried out on behalf of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Species Survival Commission’s Cat Specialist Group.

The ALD initiative, which is funded by the Lion Recovery Fund and National Geographic, aims to consolidate lion population, distribution and mortality data from across their range.

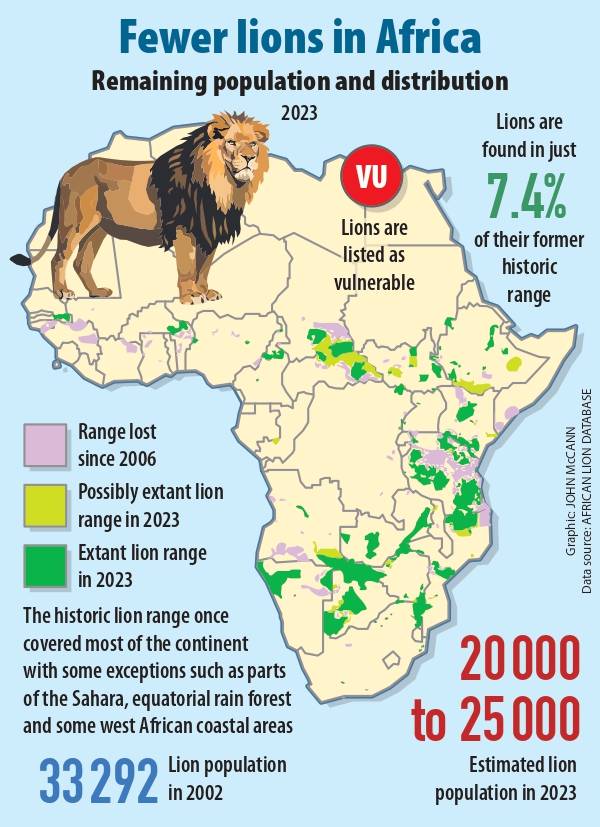

Recent estimates, Nicholson said, suggest that between 20 000 and 25 000 individuals remain in Africa, where they are listed as vulnerable by the IUCN on the Red List of Threatened Species.

“Unfortunately, when we look at the data we estimate that in the last three lion generations (21 years), lions have lost about 36% of their range,” Nicholson said. “That is concerning and some of our key populations are also under threat.”

As top predators, lions maintain biodiversity and the integrity of ecosystems, but their future is precarious. “Not many people are aware of how lions are really facing some severe issues and there’s real conservation concern for the species overall,” she added.

South Africa’s lions faring well

According to the 2016 Red List Assessment, lion numbers have been plummeting dramatically across the continent. However, in South Africa, the lion population is stable or increasing in major reserves and rising through the addition of small reserves or the formation of conservancies.

The country’s free-roaming wild lions are listed as a conservation species of “least concern” by the IUCN. It’s likely there are about 3 000 wild lions in South Africa, based on the ALD. Lion populations in South Africa, Nicholson said, are stable or potentially increasing.

As nearly all of South Africa’s lions are in fenced reserves, human wildlife conflict is not a threat that is as significant as in Tanzania, or Kenya for example, she said, noting though that it is experienced around some areas of Kruger, Mapungubwe and the Kgalagadi.

At a continental level, habitat loss and the loss of prey base are the two most significant threats to lions. “But in South Africa, because we have our fenced reserves, they are potentially more protected, habitat is secure and the prey base is managed within them.”

Poisoned, killed in snares

What worries Nicholson, however, is the increase in lion poaching, which includes the targeted poaching of lions for their body parts in South Africa including their paws, claws, teeth, skins – and even their intestines.

SANParks recently confirmed that for the period January 2020 until the end of June this year, eight lions were found poisoned in the Xanatseni north region of the Kruger, with a further six lions killed in snares over the same period, as reported by Daily Maverick.

It told the publication that considerable efforts are being made to monitor the lions in the far north of the park and it is working closely with the EWT to fit monitoring and tracking collars on the remaining prides, with field rangers patrolling areas, too, that are known hotspots for snaring and removing snares.

According to Nicholson, poaching lions for their body parts is a very real threat. “It is not a common occurrence in many of our fenced reserves, but rather more in the larger systems like the Greater Limpopo Transfrontier Area, although there have been a few poaching incidents in Dinokeng Game Reserve where parts have been removed …

“Whether it’s for local muti or the international [wildlife trade], it’s kind of hard to really know … The threat that we really are faced with is poaching, both indirect and direct, usually poisoning or snaring.

One example is the Kruger, “where we are seeing an increase in these threats and it’s likely that populations are declining”, she said. “But we do know that most of the northern area of the Kruger has potentially declined in lion numbers.”

As the Kruger fence is open to the Limpopo National Park in Mozambique, “you’re faced with additional pressures from a neighbouring country, so you could potentially have poachers moving in and out, sometimes undetected”. And, because it’s such a large system, poaching patrols are more challenging.

South Africa and Mozambique are probably the two countries that see the most targeted lion poaching for their parts, Nicholson said.

“However, the data for South Africa in the ALD is mostly from captive facilities, but poaching for parts has occurred in Dinokeng and Kruger, specifically the northern area of Kruger, and the Greater Mapungubwe Transfrontier Conservation Area.”

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

‘No empirical evidence’

Currently, there is no empirical evidence that lions are being targeted, according to Isaac Phaahla, spokesperson for SANParks.

“However, in 2021 in Punda Maria, two lions were poisoned but we found their remains in a decomposed state, which made it difficult to ascertain whether parts were taken from their bodies or not … The biggest challenge in the north of the Kruger National Park is large-scale snaring, which is indiscriminate and affects all species,” he said.

“The other fact that needs to be considered is that we have a transfrontier park. Many lions have been released in the area but cross either into Zimbabwe or Mozambique and SANParks has no control over the movement as a signatory to the dropping of fences.”

Phaahla said the last stable resident lion pride in Pafuri was in 2019. “From what we can decipher, they crossed the Limpopo into Zimbabwe, where they became habitual livestock killers and we assume that the communities killed them, because they never returned.”

SANParks had reintroduced many lions in the Pafuri area over the past two years. “These lions are overflowing from the Greater Kruger National Park and have come from the Associated Private Nature Reserves (Balule) and along the Kruger’s southern border.”

The largest hurdles to them being welcomed in the prey-abundant Pafuri Valley is the huge hyena population that “harasses them to the point that they go elsewhere”.

Sustainability of lions

The biggest challenge is to ensure the sustainability of lions, Phaahla noted, citing the lack of herding and guarding of livestock in the adjacent areas to the Kruger in the transfrontier conservation area.

“When lions venture out, they first encounter unattended livestock and then quickly become habitual livestock killers.”

Another factor is the lack of value of lions in wildlife areas outside and adjoining the Kruger and Gonarezhou. Lions are only of economic value in the well-established photographic safari areas, such as the Kruger.

“Outside these areas, they have little to no value, and in fact, are not wanted as they cause large-scale damage. They used to be valued in these areas as they were a valuable contributor to the safari hunting industry, where a past territorial male lion was hunted every few years,” he said, pointing out this hunt generates in the region of $100 000.

But “thanks to the false propaganda spread by the animal rights extremist NGOs”, the lion hunting has almost stopped. As a species, it is no longer able to contribute as an economic generator. “If lions are valued in the greater system, they will not be immediately persecuted for small changes when they venture out.”

Compounding these problems are the lack of payment of compensation should a lion kill livestock in Zimbabwe. SANParks is working on projects and initiatives to solve all three of these issues and “hopefully, in time they will bear fruit”, Phaahla added.

Space to thrive

The Kruger and the Kalahari are vital for lion conservation in South Africa, said Gus Mills, a large carnivore specialist,. There, they are part of large, intact and well-managed systems. “Look, there can be a bit of poaching, but the lion populations in those two parks are doing very well …”

That their lion populations are naturally controlled and not managed by humans is important. “We need to have areas that are fully functional ecologically and we’ve got those areas that are more or less as close as you can get in this modern world,” Mills said.

In many areas, Africa’s most iconic big cat is in big trouble. Still, there are pockets of hope. “In some places we’re seeing local extinctions but then in others, we’re seeing isolated population increases or reintroductions,” Nicholson said, citing the success of projects that had reintroduced lions to Malawi, Rwanda and the Zambezi Delta in Mozambique.

The West African lion – one of two subspecies in Africa – is critically endangered in West Africa as there are fewer than 250 mature individuals remaining. Most are found in the W-Arly-Pendjari protected area complex (32 250 km2), which straddles Benin, Burkina Faso and Niger.

“Unfortunately, that area is under pressure from armed conflict and extremist groups so that makes protected area management and conservation more challenging.

“Violent extremism generates insecurity and lawlessness, which can decrease management effectiveness and can worsen threats that currently exist, such as poaching, habitat loss or human-wildlife conflict,” Nicholson said, noting there is concern about how these lions are faring, given the difficulties surveying them.

Across Africa, “we really do have these little pockets of hope and conservation successes but there are also areas that are facing significant pressures and need a little bit more attention”.