(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

President’s Cyril Ramaphosa’s unity cabinet was sworn in this week, the result of four weeks of inevitable political compromise — and no small measure of skill on his part in the art of negotiation.

The country emerged from the process with nine of the 11 parties that have signed the statement of intent in support of the government of national unity (GNU) represented in the 32-member cabinet — or among the 43 deputy ministers.

Ramaphosa has kept the ANC in power despite the loss of its 30-year parliamentary majority by accommodating his historical opponents — including the Democratic Alliance (DA) — in his new cabinet.

He managed to dilute the power of the DA in his cabinet by bringing the smaller parties into his cabinet — including the United Democratic Movement and the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania (PAC) — and also negated the argument that the unity government was a grand coalition between the ANC and the DA.

Ramaphosa responded to the DA’s negotiating team upping its demands in the closing days of talks by awarding its leader, John Steenhuisen, the agriculture ministry instead of the post of minister in the presidency.

Power remains centralised in the presidency, including intelligence and the economic and security clusters, with Steenhuisen and other DA leaders instead given portfolios that provide a sizable opportunity — and a share in the responsibility of governance — but that are far from the centre of power.

That said, Steenhuisen’s agriculture portfolio is central to food security, job creation and earning foreign exchange through the export market, and will provide the DA leader with a solid platform from which to prove himself in government.

It will also allow Steenhuisen to consolidate support for the party among its natural constituency, who have for years accused the ANC of turning a deaf ear to its concerns, including farm murders.

The DA last month took back some of the ground it had lost to the Freedom Front Plus in 2019, and Steenhuisen’s new job will give him an opportunity to build on this in the country’s agricultural heartland.

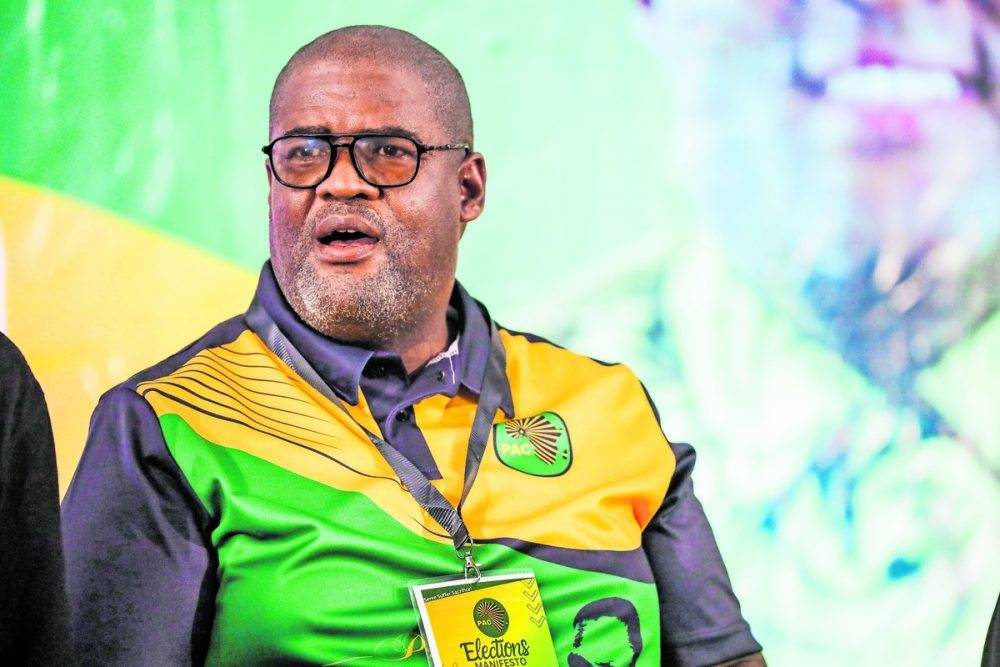

Ramaphosa made land reform a separate portfolio and gave it to the PAC’s Mzwanele Nyhontso, who has said it speaks to the core of what his party stands for. It also serves up a retort to Jacob Zuma’s uMkhonto weSizwe party, which has vowed to make land its main policy priority.

PAC: Mzwanele Nyhontso is the new land reform minister.

Photo: OJ Koloti/Getty Images

PAC: Mzwanele Nyhontso is the new land reform minister.

Photo: OJ Koloti/Getty Images

Nyhontso will now have responsibility for the Ingonyama Trust, which controls nearly three million hectares of land in KwaZulu-Natal on behalf of the Zulu king, and whose management and finances the department has been trying to regularise.

Relations between government and King MisuZulu ka Zwelithini soured ahead of the elections, and both Nyhontso and IFP president Velenkosini Hlabisa, the new minister of cooperative governance and traditional affairs, will play a role in building a better relationship with the Zulu monarchy.

Steenhuisen and Nyhontso are among nine first-time ministers from the opposition benches.

In the DA’s Dion George, the country has an environment minister who has vowed to make the just energy transition his priority.

His colleague Dean Macpherson, a politician with a healthy disregard for niceties, has said his first step as minister of public works will be to inform his cabinet colleagues that they will not get new residences and offices.

Macpherson’s bluntness may well be an asset in dealing with the site hijackings carried out by business “forums” around the country — and in ensuring that the department finally creates a register of its assets.

The DA’s former chief whip, Siviwe Gwarube, becomes the minister of basic education at the age of 34, one of several youthful cabinet members appointed by Ramaphosa.

Andrew Whitfield, 41, and Zuko Godlimpi, 32, who serve as deputies to trade, industry and competition minister Parks Tau, are among those, as is Nonceba Mhlauli, 34, the deputy minister in the presidency.

Paul Mashatile remains deputy president of the country, maintaining the tradition set in the ANC succession and ending speculation that Ramaphosa would appoint Steenhuisen — or the IFP’s Hlabisa — to the position.

Mashatile’s allies in the ANC had claimed that he was the target of a campaign aimed at preventing him from becoming president and a social media campaign pushed the scenario of Ramaphosa plotting to replace him with Steenhuisen during the coalition talks.

DA: Environment Minister Dion George (left) and Public Works Minister Dean Macpherson (right). Photos: Misha Jordaan & Darren Stewart/Getty

DA: Environment Minister Dion George (left) and Public Works Minister Dean Macpherson (right). Photos: Misha Jordaan & Darren Stewart/Getty

“He is looking for any reason to be a victim,” was how one ally of the president put it.

It was Ronald Lamola’s refusal to withdraw his candidacy for the deputy presidency of the ANC at the party’s 2022 national conference that split the vote in the Ramaphosa camp, and handed the post to Mashatile.

But Ramaphosa never punished the then justice minister. His promotion to international relations and cooperation minister is not only a reward for loyalty to Ramaphosa but for his role in South Africa’s ground-breaking approach to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) to have Israel declared in breach of its obligations under the 1948 Genocide Convention.

Although it may take the ICJ years to decide the main application in which South Africa’s legal team accuses Israel of committing genocide in Gaza, it has twice handed down interim orders meant to prevent further loss of Palestinian lives.

In May, the court ordered Israel to “immediately halt its military offensive and any other action in the Rafah governorate which may inflict on the Palestinian group in Gaza conditions of life that would bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part”.

And although Israel has flouted the orders, the court case has helped to shift international opinion on Israel’s onslaught. Spain last month became the first European country to join in the case, after recognising Palestinian statehood.

Lamola has worked closely with international relations director general Zane Dangor on the case, and his appointment will ensure continuity in a matter that has placed a leitmotif of ANC policy at the centre of the search for a just global order.

He now has the task of defining what non-alignment means in the present context and defending South Africa’s inconsistencies — its defence of Russian President Vladimir Putin refers — while demanding international law apply to all equally.

Speaking on the sidelines of the cabinet swearing-in this week, Lamola said one of his priorities would be “economic diplomacy, because the country needs investment”.

Lamola’s successor in the justice ministry, Thembi Nkadimeng, will be the first to not have a law degree.

Nkadimeng has spent decades trying to force the justice authorities to prosecute the members of the apartheid police Security Branch who abducted her sister, Nokuthula Simelane, an operative of the ANC’s uMkhonto weSizwe military wing, in 1983. Simelane was tortured at Vlakplaas and presumed murdered.

Nkadimeng has spoken of losing trust in the justice system while her family has waited to learn her sister’s fate, although the Truth and Reconciliation Commission had referred the case to the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA).

ANC: Justice Minister Thembi Nkadimeng (left) and International Relations Minister Ronald Lamola (right). Photos: Dwayne Senior & Frennie Shivambu/Getty Images

ANC: Justice Minister Thembi Nkadimeng (left) and International Relations Minister Ronald Lamola (right). Photos: Dwayne Senior & Frennie Shivambu/Getty Images

The matter is finally before court.

“Her personal history with the justice system may bring a new dimension,” said Jean Redpath, of the Dullah Omar Institute.

She described Nkadimeng, who served 14 months as minister of cooperative governance before the May elections, as hard-working and well qualified, and credited her with largely organising a recent indaba at the institute on the effect of coalition governance on political ecosystems.

Mbekezeli Benjamin, of the watchdog NGO Judges Matter, said he was pleased to hear Nkadimeng promptly list her priorities as dealing with corruption, gender-based violence and court infrastructure. All are burning issues, and she intends to work closely with the public works department to improve the dire state of the courts.

The NPA and the wider justice system has been hobbled by poor policing and there is relief that Ramaphosa has replaced Bheki Cele with Senzo Mchunu in that portfolio.

But his decision to give the critical water and sanitation portfolio to former chief whip Pemmy Majodina inspires less hope. So does the appointment of her deputy, David Mahlobo, the former intelligence minister who was accused in testimony before the Zondo commission of subverting state intelligence to serve former president Zuma’s political aims.

Few choices have elicited as much dismay as leaving mineral resources in the hands of Gwede Mantashe, on whose watch investment in mining has dwindled to levels last seen more than half a century ago.

His failure to make the mining and exploration licence application process fit for the 21st century has much to do with the decline. Ramaphosa knows the cost to the economy and the only explanation for his choice is repaying and retaining Mantashe’s “remarkable loyalty”, as an insider put it, in the ANC’s factional wars and two weeks of coalition decision-making.

Splitting energy into a separate portfolio and assigning it to Kgosientsho Ramokgopa has been both expected and welcomed, in large part because it means an end to Mantashe’s custodianship of the Integrated Resource Plan and his stonewalling on renewable power.

It is worth remembering that Mantashe tabled a bill to create a new state-owned petroleum company under the control of his department. It created a tug of war with the public enterprises department, which Ramaphosa has settled by adding petroleum to his portfolio.