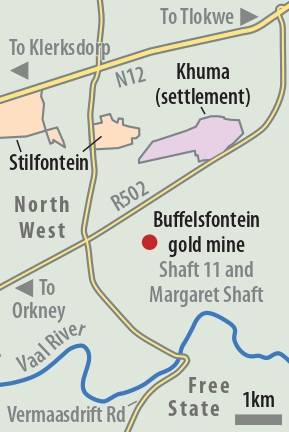

Digging deep: Residents of the township of Khuma, near the Buffelsfontein mine in Stilfontein, North West, where zama zamas are trapped underground, say they are suffering economically after a police operation shut down illegal mining activity. Photos: Lunga Mzangwe

Barely 10km from the abandoned Buffelsfontein mine in Stilfontein, North West, where hundreds of illegal miners remain underground, lies the dusty township of Khuma. The local economy is heavily dependent on the zama zamas’ operations.

The decision by police and soldiers to block supplies to the miners to force them back to the surface, as part of Operation Vala Umgodi points to a bleak future for many local businesses and for residents who depend on the illicit mining activities for an income.

Launched last year, Vala Umgodi is a government-led crackdown in response to an increase in illegal mining — including direct attacks on mine sites and infrastructure, fuelled by soaring gold prices.

In the past month, more than 1 000 miners have resurfaced from the Buffelsfontein mine as a result of the operation, according to police spokesperson Athlenda Mathe.

Many have been arrested.

The Mail & Guardian visited businesses in Khuma this week and found that they were unhappy about the massive police presence at the abandoned mine.

There is a strong feeling of neglect about the township. Roads are potholed and raw sewage flows in some of the streets, where teenagers and young adults roam around or sit in corners, their faces filled with frustration and hopelessness.

Eatery owner Thandi Motloung has had to shut down her business indefinitely as a result of the drop in sales due to the heavy police presence in and around the area.

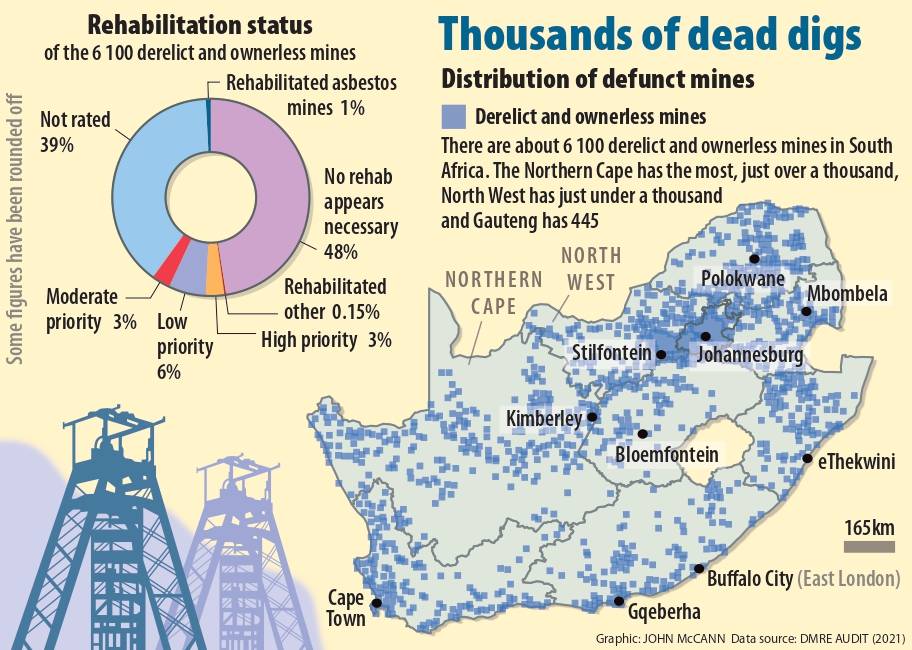

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

Prior to closing shop, Motloung said she had been working at a loss for a while because sometimes only one customer a day would buy her food. Previously, she made about R500 a day but lately this had plummeted to R60.

The decision to shut down has dire consequences for Motloung’s family as she won’t be able to afford many basic necessities, let alone new clothes for her children for the festive season, an annual tradition.

“The past two weeks we have been sending children to school without pocket money and where will we get money for Christmas clothes?” the despondent Motloung said.

“We really need the government to find a solution with the zama zamas because we all survived because of that abandoned mine.”

A local spaza shop owner, who identified himself only as Chris, said his business had suffered as most of his customers were stuck underground.

There were other problems too: “No one has money to buy. People are coming here to ask for help. Most of them are foreign nationals and they can’t be hired anywhere.

“The zama zama job is the only thing that gives them a living and they can’t go home because it’s better here in South Africa,” Chris said.

At a local tavern, described by residents as the place to go to have fun, patrons were sitting on beer crates, eating ice lollies.

They told the M&G that the situation in the township was so dire as a result of the presence of the police at the mine and the shutdown of the zama zama’s activities that even lollies had become a luxury.

The tavern’s owner, who identified herself only as Paulina, said she had been to the mine to show solidarity with those stuck underground because they were the ones who kept her business afloat.

Paulina said her tavern had always been busy, but since the police intervention, she’s lucky to have 10 customers a day buy a beer each.

“You can also see, people are eating ice lollies at a tavern. It tells you how bad things are.

“The ones who support me are underground and at this point, we are stuck,” she said.

Khuma residents told the M&G that, in addition to losing their source of income, the situation at the mine would result in an increase in crime in the area as nobody could earn a living from the mine.

“This will mean that crime will start again — and it has been low because people were working,” one lamented.

Prior to this, crime had been at an all-time low in part because of the zama zamas, who often helped deal with those committing the misdemeanours.

“If you were found stealing or mugging people, the zama zamas would force you to go to the mine and start working there.

“People were able to walk at night without any fear but now crime will be on the rise because people are hungry,” another resident said.

In the past two weeks, 10 miners and one body have been pulled to the surface by local rescuers using ropes.

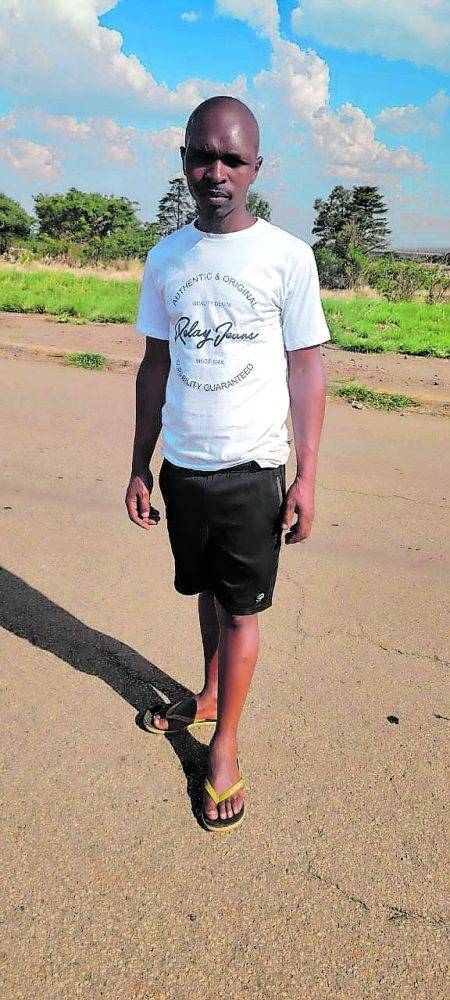

Rescued: Ayanda Ndabeni is one of the illegal miners who was hauled out of the Buffelsfontein mine in Stilfontein.

Rescued: Ayanda Ndabeni is one of the illegal miners who was hauled out of the Buffelsfontein mine in Stilfontein.

Among those rescued was Ayanda Ndabeni, who said he had been underground for two months and that those stuck below had been forced to survive on salt water.

He said their struggle for survival had started a month ago with the arrival of police acting under Operation Vala Umgodi.

Ndabeni said those underground were starving and that some were in serious need of medication for chronic illnesses.

This was apparent on Monday when the miners sent up a note pleading for antiretroviral drugs for those living with HIV.

The exact number of miners still underground is unknown but police intelligence suggests there could be 300 to 400.

However, Ndabeni said the figure was much higher.

“The level I was in, we were plus or minus 800 people.

“We lost one person and it’s that person who was brought up on Thursday last week.

“On the other levels, I don’t know how many people died because there are a lot of people underground,” Ndabeni said.

“There are a lot of levels and some of them we can’t even reach.

“The levels I know are eight and I was in level 17.”

Ndabeni said his wife, children and community were happy that he was still alive but he was now in a position where he could no longer feed his family.

He said that those who were mining illegally were prepared to sit down with the government to find a solution for them to be allowed to carry out their activities within the law and support their families.

“We come here in the veld to get things that have been left by mine owners who think there is no use for them, which we view as being thrown away.

“We take them, so that we can live,” he said.

A gram of gold dust retrieved from the mine was worth R1 000 on the black market.

“When we come out with the gold, we take it to the people who are able to buy it, then that person will see where they will sell it.

“That person will get more money than what they give you. If you are lucky, and get 500g, then you have R500 000,” Ndabeni said.

“There’s no one who robs you.

“The only people who will maybe disturb you are the police.

“Most of the people can’t put it in the bank because they fear it will be confiscated when they start asking where they got the money, so you end up hiding it in the house.

“Once the police find it in the house, it is taken because I think the law says you can’t keep more than R10 000 in the house.”

Ndabeni, who usually mines about 30g of gold a month, said he had been forced to leave what he had collected when he was brought to the surface as he would have been arrested if he had been found with it.

“I was avoiding having a criminal record and things like that.

“When I was rescued, they let me go because I don’t have previous criminal records and I’m not a person who is always in trouble with the law,” he said.

He would not think twice about going back into the mine — if he could do so without risking arrest.

“I would go back now. I wouldn’t even go back to the township, I’d just send a message to my wife and children that I’m going back to work,” Ndabeni said.

“My wife would agree for me to go back because she knows I paid lobola with the money of this life I live.

“I met her living this life. She knows that I provide for our family this way.”

If they were not allowed to go back, the miners would be forced to live on social grants, he said.

Ndabeni said he had been working in the mine for many years without any problems, but since the introduction operation Vala Umgodi, lives have been turned upside down.

A group of zama zamas, who asked to remain anonymous, said they wanted the government to give them permits allowing them to mine without having to look over their shoulders, fearing arrest.

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

They said no one was taking responsibility for the mine and they were not bothering or stealing from anyone as it had been abandoned.

“The owner left here a long time ago. It belongs to the community now. The people who go to the mine are there to try and make a living.

“We say this belongs to the community because no one is taking responsibility for it,” one of the zama zamas told the M&G.

“A lot of people benefit from this mine and the economy of the community is based on this.”

“We grew up with money from this mine,” another added.

“The shops in the community are supported by this very same mine. We don’t steal from anyone, we just zama zama from this mine and bother no one.”

They said that, because of the lack of job opportunities in the area, illegal mining was the only way to make a living.

“We have been looking for jobs for a long time. We went to school, got qualifications but we have no jobs.

“Some of the guys have certificates from their time in prison but none of them is hired because they have a criminal record.”

“Such people will never get an opportunity, so this is an honest way for them to make a living and to feed their families.”

The group said that they disagreed with closing the mine shafts because this would lead to even more problems.

“Crime would definitely rise. Since we started mining here, things like people robbing others were things of the past.

“People could even walk around at 4am with no fear of being robbed,” the zama zama added.