Gentle giants: Manta rays, which can reach a span of seven to eight metres, are found in warm waters. Reef mantas are found along coastlines and oceanic mantas in open waters

Getting tapped on the head by a manta ray’s pectoral fin, being enveloped and hugged by another and playing hide and seek are just some of the encounters that marine biologist Michelle Carpenter has had while swimming with the world’s largest rays in the waters of Indonesia, Mozambique and South Africa.

“They just let me in their train one day when I followed [it] and then a few followed behind me, playing hide and seek, where you just duck under the reef and then they come and peek over you,” said Carpenter, a collaborator with the Marine Megafauna Foundation, Clansthal Conservancy and Manta Trust.

Most South Africans don’t realise they can see manta rays without leaving the country, she said.

“We’re home to the reef manta ray and the oceanic manta ray, the latter reaching an impressive eight metres wingtip to wingtip, making it the largest ray in the world.”

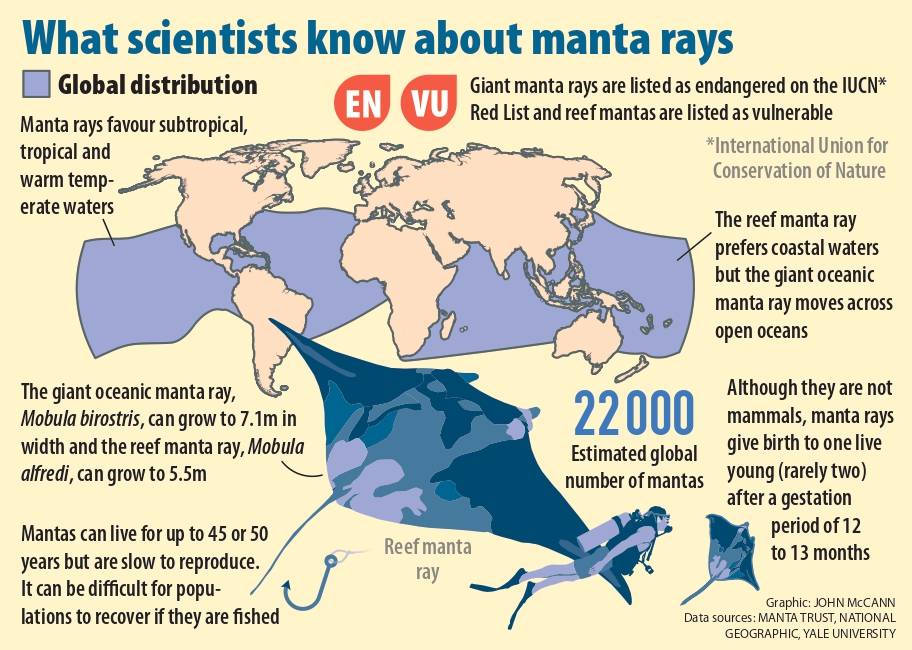

But humans have caused significant population declines of these graceful creatures. Trawling, tuna purse seine nets, gill nets in Mozambique, shark nets in South Africa, and seismic testing by oil companies all pose threats. The oceanic manta ray is globally endangered and the reef manta is listed as globally vulnerable.

Much more needs to be done to protect them from unsustainable fisheries.

Carpenter spearheaded a nationwide collaborative study with a team of fellow marine biologists that has uncovered some of the mysteries of South Africa’s manta rays.

Among the discoveries of this first in-water assessment of manta ray aggregations is that the iSimangaliso Wetland Park in northern KwaZulu-Natal is a critical habitat for reef manta rays.

The study, published in the journal Environmental Biology of Fishes last month, revealed unique characteristics of the mantas, including highly mobile reef mantas, rare black oceanic mantas, newfound feeding aggregations and potential baby manta nurseries.

Mantas, with their flat, diamond-shaped bodies, play a vital role in ocean health and could drive tourism revenue in KwaZulu-Natal, said Carpenter, who dedicated her PhD at the University of Cape Town to manta rays and has held a lifelong fascination with these gentle giants.

Manta rays, which glide effortlessly through the water, are often called the wings of the sea because of their large, triangular pectoral fins that resemble wings.

Very little research has been done on South Africa’s manta rays.

Very little research has been done on South Africa’s manta rays.

“They are the largest rays in the world and we know so little about them, for instance in South Africa, an entire country that hasn’t been examined for manta rays,” Carpenter said. “They’re highly charismatic and they’re very intelligent,” said Carpenter.

“They have the largest brain-to-body size ratio of all fish and it’s apparent in your interactions with them,” she said. “The first interaction I had with them, you just feel this sentient, aware being and they come and stare at you in the eye, or they play around with you; they seek out interactions with you. And this is a fish we’re talking about.”

Humans do not give fish the credit they deserve, she added. “They’re intelligent animals and I think because we like to ignore their intelligence, and their sociality and the ways that they are like us. It makes it easy for us to over-exploit them, which we are doing.”

Mantas are filter feeders that eat zooplankton, the smallest marine animals, and have the capacity to dive to extraordinary depths — more than 600m deep for the reef manta ray and at least 1 400m deep for the oceanic manta ray.

“They travel really far but are still able to return to the exact same locations year after year, where they clean or they feed,” said Carpenter.

“They have complex behaviours, which we are only starting to scratch the surface of. That includes their behaviour on clean stations [where fish help remove parasites and clean mantas’ wounds] and their sociality. They have social groupings with each other; they spend their lives or decades with specific individuals.”

For their study, the researchers collated citizen science observations since 2003 to reveal six areas in KwaZulu-Natal and the Eastern Cape where manta rays have been sighted across multiple years.

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

They used their ventral spot patterning — the unique spot patterns on the bellies of manta rays — to identify individuals. A total of 184 were photo-identified, comprising 139 reef manta rays and 45 oceanic manta rays.

In iSimangaliso Wetland Park, the researchers discovered manta ray feeding aggregations in a marine sanctuary protected from fishing and recreational diving for more than 50 years. Here, 89% of South Africa’s reef manta sightings have been recorded.

This aggregation area in a restricted-access sanctuary is a haven amid threats along the coastline, said Nakia Cullain, of the Marine Megafauna Foundation.

“The whole park was recently named a Mission Blue Hope Spot, joining a network along South Africa’s coast that includes Aliwal Shoal and Cape Town.”

South Africa’s sanctuary demonstrates how effective marine protection can support not only manta ray aggregations but other species as well, providing a valuable model for countries such as Mozambique, which lack extensive marine protection, Cullain said.

A team of marine scientists (above left and right) have made new discoveries about manta rays along South Africa’s coastline, including their brain size and cleaning stations and nurseries

A team of marine scientists (above left and right) have made new discoveries about manta rays along South Africa’s coastline, including their brain size and cleaning stations and nurseries

Research in iSimangaliso and other areas such as the Aliwal Shoal has shown significant connectivity to Mozambique. One manta travelled 1 305km multiple times between Zavora, Mozambique, and iSimangaliso. Another travelled more than 600km from the Pondoland Marine Protected Area (MPA) to iSimangaliso.

A juvenile seen in Pondoland in 2016 was later seen again as a pregnant adult in iSimangaliso. Two mantas made repeat trips between Zavora and iSimangaliso in a 870km round trip. Then, 28 mantas were identified in Mozambique, with most linked to Zavora.

Carpenter noted that these movements are potentially driven by the availability of zooplankton abundances, which are transient along the coastline and with seasonal patterns.

“While mantas have been officially documented in South Africa since the 1950s, shifts in their movements could be linked to climate change, with rising water temperatures affecting currents and food availability,” she said.

Ryan Daly, a specialist in shark and ray movement patterns, said that because these animals cross borders, conservation management plans need to be aligned between South Africa and Mozambique to protect their populations.

Oceanic mantas are infrequent in South Africa’s waters, with sightings concentrated in Ballito, the Aliwal Shoal and the Pondoland marine protected areas.

Researchers were buoyed to discover rare melanistic (black) oceanic manta rays in the Aliwal Shoal in February 2020 and in Ballito in November 2021.

It was not previously known that melanistic oceanic mantas inhabited these waters, Carpenter said.

“Genetic studies suggest no distinct population groupings, but regional differences in melanism are likely tied to localised groupings, with gene flow facilitated by long-distance travel,” she said.

The researchers extended the southern range for reef mantas in Africa by more than 500km from Mdumbi Beach near Coffee Bay on the Wild Coast to Port Ngqura near Gqeberha, which may be at least one seasonal nursery area in Southern Africa, during summer.

The presence of both species across all areas in the study indicates that South Africa encompasses the distribution ranges of both species, with each species showing particular preferences for specific habitat.

“With 1 300km plus of coastline in this study, this preliminary assessment suggests there are likely many more sites yet to be described, which is critical for informing the designation of marine protected areas to protect these particularly threatened populations of manta rays,” Carpenter said.

South Africa is a difficult place to study manta rays, “because the coastline is huge and highly remote. There are not many places on this coastline that people are regularly diving in, if you consider the amount of area versus regular recreational dive spots.

“Plus, we have extreme conditions, which makes it understandable that we don’t have that many recreational dive spots: the turbid waters, the currents, the swell, the remoteness of different places. It’s a very tricky coastline to work on.”

Carpenter said it was not known whether manta rays have always been present in high numbers or whether this is the southerly distribution home range for these species.

“We don’t know how long manta rays have actually been here because no research has been done on them and there’s a lack of awareness on sharks and rays in general.

“And because they’re using so much of the coastline and not always aggregating somewhere — or if they are, it’s probably somewhere [remote] — all this contributes to the fact that most people don’t know they’re here.”

She said a lot more scientific work needs to be done.

“We still need to get enough photo IDs to start analysing the population abundance.”

Carpenter wants the research to help improve the management of South Africa’s manta species.

“The reef mantas are one of the most threatened populations in the world — if not the most threatened in the world — and I really want more attention and focus being done … as well as on the endangered oceanic mantas and the endangered short-fin devil ray,” she said.

She also hopes their study will inspire more efforts, especially among locals, to become involved in marine biology.

“Even if you’re not involved in marine biology, there’s so many ways you can help the ocean — by spreading awareness, choosing to eat seafood very specifically and not eating fish that are over-exploited or buying fish from people that use unsustainable methods like tuna purse seine nets, trawling or gill nets — and just being an aware consumer.”