How can data help the health department make the most of the R622 million extra it received for South Africa’s HIV treatment programme? (Flickr)

More than two weeks ago, Health Minister Aaron Motsoaledi announced that the treasury has given R622 million of emergency funding to his department to prop up South Africa’s HIV treatment programme.

About R590 million is for provinces’ HIV budgets and R32 million for the chronic medicine distribution system, which allows people to fetch their antiretroviral treatment from pick-up points other than clinics, closer to their homes.

This extra budget is just over a fifth of the roughly R2.8 billion funding gap that the health department says the country needed after the Trump administration pulled the plug on financial support for HIV in February. (The Pepfar budget for this financial year was just under R8 billion, but the health department calculated that it could fill the void with R2.8 billion if it trimmed extras and ruled out duplicate positions.)

So, how to get the best bang for these limited bucks — especially with the health department wanting to get 1.1 million people with HIV on treatment before the end of the year and so reach the United Nations targets for ending Aids as a public health threat by 2030?

By getting really serious about giving people more than one way of getting their repeat prescriptions for antiretroviral (ARV) medicine (so-called differentiated service delivery), said Kate Rees, co-chair of the 12th South African Aids Conference to be held later this year, from Kigali last week, where she attended the 13th IAS Conference on HIV Science.

At another Kigali session, Lynne Wilkinson, a public health expert working with the health department on public health approaches to help people to stay on treatment, said: “People who interrupt their antiretroviral treatment are increasingly common, but so are people who re-engage, in other words start their treatment again after having stopped for a short period.”

A big part of South Africa’s problem in getting 95% of people who know they have HIV on ARVs (the second target of the UN’s 95-95-95 set of cascading goals) is that people — sometimes repeatedly — stop and restart treatment.

For the UN goals to be reached, South Africa needs to have 95% of people diagnosed with HIV, on treatment. Right now, the health department says, we stand at 79%.

But the way many health facilities are run makes the system too rigid to accommodate real-life stop and start behaviour, says Rees. This not only means that extra time and money are spent every time someone seemingly drops out of line and then comes back in, but also makes people unwilling to get back on board because the process is so inconvenient and unwelcoming, she says.

Rees and Wilkinson were co-authors of a study published in the Journal of the International Aids Society in 2024, of which the results helped the health department to update the steps health workers should follow when someone has missed an appointment for picking up their medicine or getting a health check-up — and could possibly have stopped treatment.

“We often have excellent guidelines in place, built on solid scientific evidence,” says Rees, “but they’re not necessarily implemented well on the ground.”

To make sure we track the second 95 of the UN goals accurately, we need a health system that acknowledges people will come late to collect their treatment and sometimes miss appointments. This doesn’t necessarily mean they’ve stopped their treatment; rather that how they take and collect their treatment changes over time.

The standard ways in which the public health system works mostly doesn’t provide the type of support these patients need, as the resources required to provide such support is not available,” explains Yogan Pillay, the health department’s former deputy director general for HIV and now the head of HIV delivery at the Gates Foundation.

“But with AI-supported digital health solutions and the high penetration of mobile phones, such support can now — and should be — be provided at low cost and without the need to hire additional human resources.”

We dive into the numbers to see what the study showed — and what they can teach us about making the system for HIV treatment more flexible.

Does late = stopped?

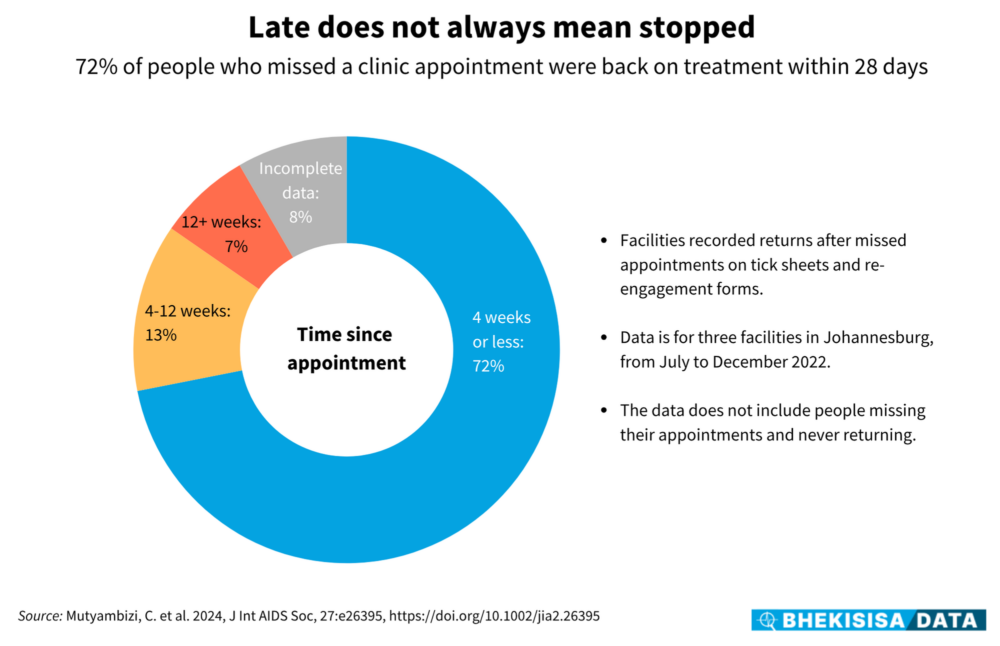

Not necessarily. Data from three health facilities in Johannesburg that the researchers tracked, showed that of the 2 342 people who came back to care after missing a clinic appointment for collection medication or a health check, 72% — almost three-quarters — showed up within 28 days of the planned date. In fact, most (65%) weren’t more than two weeks late.

Of those who showed up at their clinic more than four weeks after they were due, 13% made it within 90 days (12 weeks). Only one in 14 people in the study came back later than this, a period by which the health department would have recorded them as having fallen out of care. (Some incomplete records meant the researchers could not work out by how much 8% of the sample had missed their appointment date.)

The data for the study was collected in the second half of 2022, and at the time national guidelines said that a medicine parcel not collected within two weeks of the scheduled appointment has to be sent back to the depot.

“But it’s important to distinguish between showing up late and interrupting treatment,” notes Rees. Just because someone was late for their appointment doesn’t necessarily mean they stopped taking their medication. Many people in the study said they either still had pills on hand or managed to get some, despite not showing up for their schedule collection.

Pepfar definitions say that a window of up to 28 days (that is, four weeks) can be tolerated for late ARV pick-ups. Pepfar is the United States HIV programme, which funds projects in countries such as South Africa, but most of them were cut in February.

Research has also shown that for many people who have been on treatment for a long time already, viral loads (how much HIV they have in their blood) start to pass 1 000 copies/mL — the point at which someone could start being infectious again — about 28 days after treatment has truly stopped.

Sending back a parcel of uncollected medicine after just two weeks — as was the case at the time of the study — would therefore add an unnecessary admin load and cost into the system. (Current health department guidelines, updated since the study and in part because of the results, say that a medicine pick-up point can hold on to someone’s medicine for four weeks after their scheduled appointment.)

Does late = unwell?

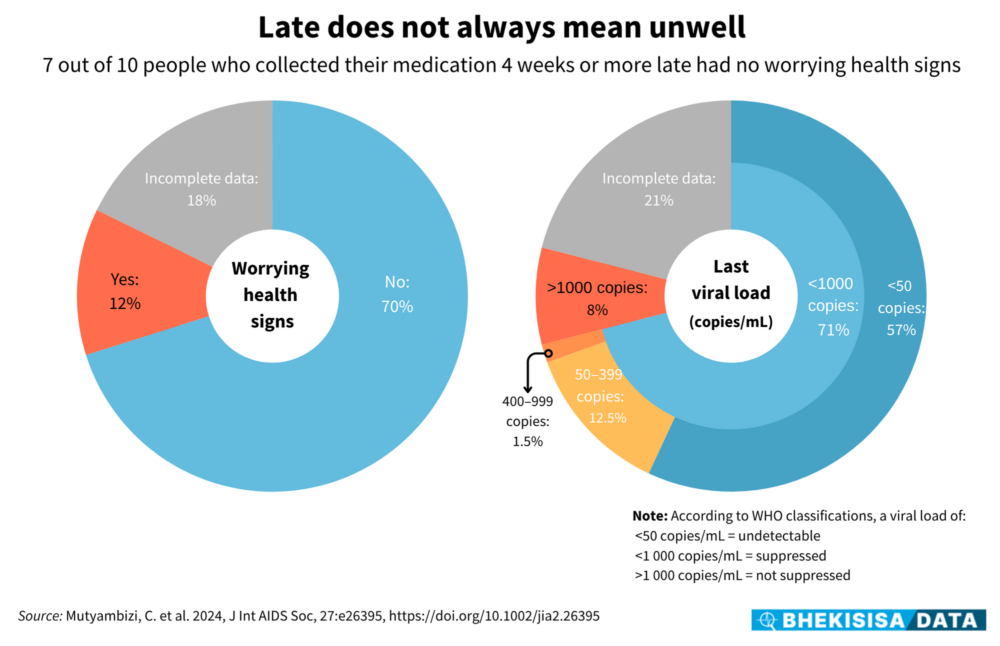

Not always. In fact, seven out of 10 people who collected their next batch of medication four weeks or more late had no worrying signs, such as possible symptoms of tuberculosis, high blood pressure, weight loss or a low CD4 cell count, when checked by a health worker. (A low CD4 count means that someone’s immune system has become weaker, which is usually a sign of the virus replicating in their body.)

Moreover, given the large number of people without worrying health signs in the group for whom data was available, it’s possible that many of those in the group with incomplete data were well too.

When the researchers looked at the patients’ last viral load results on file (some more than 12 months ago at the time of returning to the clinic), 71% had fewer than 1 000 copies/mL in their blood.

A viral count of <1 000 copies/mL tells a health worker that the medicine is keeping most of the virus from replicating. It is usually a sign of someone being diligent about taking their pills and managing their condition well.

Yet clinic staff often assume that people who collect their medicine late are not good at taking their pills regularly, and so they get routed to extra counselling about staying on the programme.

“Most people don’t need more adherence counselling; they need more convenience,” says Rees. Offering services that aren’t necessary because of an inflexible process wastes resources, she explains — something a system under pressure can ill afford.

Says Rees: “With funding in crisis, we really have to prioritise [where money is spent].”

Does late = indifferent?

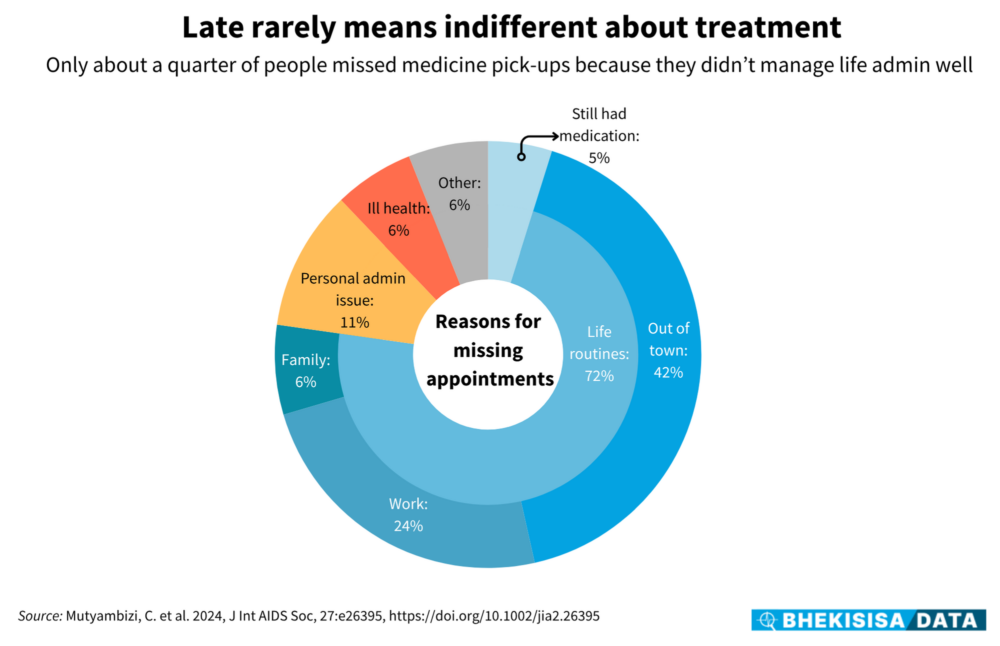

Rarely. Close to three-quarters of people who turned up four weeks or more after their scheduled medicine collection date said they had missed their appointment because of travelling, work commitments or family obligations. Only about a quarter of the sample missed their appointment because they forgot, misplaced their clinic card or for some other reason that would suggest they weren’t managing their condition well.

Part of making cost-effective decisions about how to use budgets best is to offer differentiated care”, meaning that “not every patient coming back after a missed appointment is treated the same way”, says Rees. Health workers should look at how much the appointment date was missed as well as a patient’s health status to decide what service they need, she explains.

Giving people who’ve been managing their condition well enough medicine to last them six months at a time can go a long way, Wilkinson told Bhekisisa’s Health Beat team in July. “Getting 180 pills in one go reduces the number of clinic visits [only twice a year], which eases the workload on staff. But it also helps patients to stay on their treatment by cutting down on their transport costs in their own time off work,” Wilkinson said.

Zambia, Malawi, Lesotho and Namibia have all rolled out six-month dispensing — and have already reached the UN’s target of having 95% of people on medicine at a virally suppressed level.

According to the health department South Africa will start rolling out six-month dispensing in August.

“But not everyone wants this,” explained Wilkinson, pointing out that experiences from other countries show that 50% to 60% of people choose six-monthly pick-ups.

It speaks to tailoring service delivery to patients’ needs, says Rees, rather than enforcing a one-size-fits-all system when more than one size is needed.

Says Rees: “Facing funding constraints, we really need tailored service delivery to keep the [HIV treatment] programme where it is.”

This story was produced by the Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism. Sign up for the newsletter.