Take a bow: Siya Charles, winner of this year’s Standard Bank Young Artist Award for Jazz performs on stage. Photo: Mark Wessels

It’s rare to hear a musician describe themselves as a “musician’s musician”. Yet, in a conversation preceding this year’s edition of the Standard Bank Joy of Jazz, trombonist Siya Charles, the 2025 Standard Bank Young Artist Award for Jazz winner, uses the term self-referentially. I don’t think she’s bragging though.

We’re discussing how the past 10 months since winning the award have gone, which is when it becomes clearer that she means it more in the sense that she is yet to find commercial success.

And yet, with the resources she has at her disposal as a result of winning the award, she feels relaxed enough to “create the music that is true to me” when it comes time to record her debut album in the first half of next year.

Speaking over voice notes about two weeks before the festival, we delve deeper into the history of the Standard Bank Young Artist (SBYA), with me arguing the awards have historically been rather conservative in their choice of winners, particularly in the apartheid days.

Johnny Clegg, for example, received the award in 1989 after his momentous, decade-long run of albums with Juluka (alongside Sipho Mchunu) was already behind him.

Just a year before, playwright Mbongeni Ngema had been awarded the prize for drama — believe it or not — the same year he staged Sarafina on Broadway.

“It’s true you do need a certain amount of success behind you,” Charles says. “But what I do appreciate about the SBYA is that they base the award on merit more than commercial success.”

For Charles, the award represents a culmination of 20-plus years of development and involvement in jazz education. Her debut at the National Youth Jazz Festival happened in 2005 when she was “a socially awkward 14-year-old”, probably wielding an outsized trombone.

Siya Charles accepts her SBYA award.

Siya Charles accepts her SBYA award.

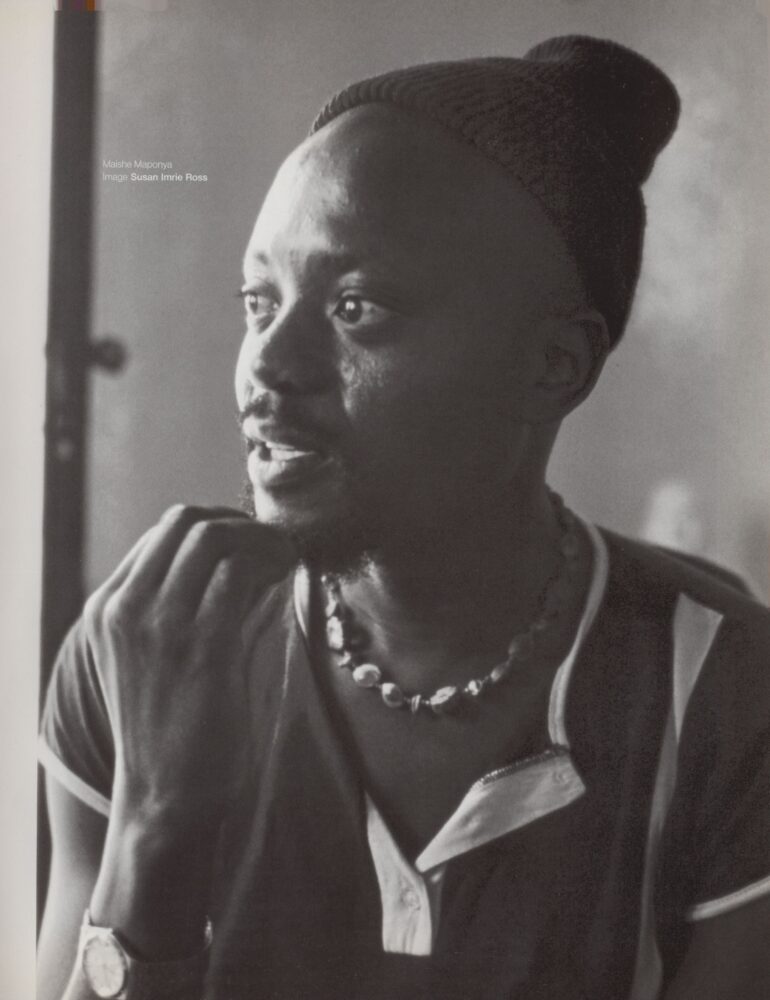

In 1985, poet and playwright Maishe Maponya became the first black artist to win the SBYA award. He took home the prize for drama in a decision that signalled the winds of change for the then 11-year-old festival still in the grips of a colonial mandate.

The awards themselves had been initiated by the festival committee in 1981, and were covered by the umbrella sponsorship of Five Roses before Standard Bank acquired the naming rights in 1984. These were rights they kept even as they lost the naming rights to the festival itself in 2002.

Maponya’s decision to accept the award followed wide consultation about the potential ramifications. Ultimately, he accepted it in order to “address a different audience and give it to them if they did not know what resistance theatre or art were” .

Former National Arts Festival artistic director Ismail Mahomed says Maponya’s win “was an opening for him and a majority of black people who [then] got involved in the festival to use it as a platform to express their political and creative voice.”

Maponya, a member of the Allah Poets since the mid-Seventies, wrote his first play The Cry in 1975.

He went on to study theatre writing and directing in the UK, staging the celebrated play The Hungry Earth with the Bahumutsi Theatre Company at the Edinburgh Festival in 1983.

In 1985, the year he won the award, he staged two more plays in Edinburgh, namely Dirty Work and Gangsters, which, as Andile Xaba writes in Daily Maverick, “simply exposed the [apartheid] regime as gangsters”.

Maponya’s activist clout imbued the SBYA award with the right kind of cachet, giving it, in his own words, “its first baptismal of transformation and political relevance”.

Mahomed argues that the political symbolism of Maponya’s acceptance of the award had a knock-on effect on the festival as a whole.

“Institutions like the University of the Western Cape and the University of Durban-Westville, which had stayed away from the Student Theatre Festival, particularly in the early Eighties [decided to get on board] …

“When the festival began to change and [re]create the fringe as a dynamic space of free expression, that’s when it became more inclusive in some ways and lost some of that negative identity of a British settler colonialist style of festival that it had,” he said.

Around the same period, the music category of the SBYA was mostly going to classically trained musicians, alternating between jazz and classical music in the mid-Nineties, until Tutu Puoane won the first separate jazz category in 2004.

Jazz and music were first handed out together in 2007, going to saxophonist Shannon Mowday (who returned from Australia upon being given the award) and soprano Bronwen Forbay, respectively.

With South Africa continuing to evolve as a society, the insistence on classical music and, in fact, genre, was bound to come across as restrictive and anachronistic. The values behind the music soon became the primary benchmark.

“It’s not about how popular your music is but how it adheres to artistic integrity and creative passion,” said director of the then Standard Bank Jazz Festival, Alan Webster, in 2009.

“You will need to be recognised and admired by your musical peers. You will also need to be on a sustainable trajectory, personally and professionally.”

“You look for people who don’t just make good music,” Sibongile Khumalo, then chair of the National Arts Festival committee, said in 2009, “but who contribute other things to society … just something else besides their musical sensibilities.”

Webster and Khumalo, herself a music category winner in 1993, made the remarks in the Standard Bank Young Artist Awards, 25 Years book, an insightful record of the award committees’ sensibilities as the country crossed over from apartheid to democracy.

Singer Sibongile Khumalo

Singer Sibongile Khumalo

At times it makes a strong case for those who argue that the brand always wins.

In the book’s foreword, then group CEO Jacko Maree, is matter of fact about the sanitising effect of the bank’s association with the arts.

“It’s important for us not just to be seen to be providing banking services and making money,” he says.

“Because we have been such an integral part of South Africa, having been around for 150 years, we have to do a number of things that show that we have a sense for the communities, for the society in which we operate.”

When Standard Bank Young Artist Awards, 25 Years appeared in 2009, it was as a “commemorative supplement” to Classic Feel magazine.

The writers state that what differentiates the awards from others is that Standard Bank, where possible, “has endeavoured to continue providing the artists with a platform after they have become winners”.

“These are ongoing relationships,” says group head of sponsorship Bonga Sebesho. “I mean Nduduzo [Makhathini] won in 2015 and we’ve got an amazing relationship with him. We follow all their careers all the time, so we support them from that perspective. They can [approach us for the funding of specific projects] or we support them from a social media perspective.

“We engage with all their content all the time. We don’t have endless resources but, from a social media marketing perspective, we’re really able to get that.”

In the right key: Nduduzo Makhathini, winner of the SBYA award in 2015, left, and poet and playwright Maishe Maponya, the first black winner, above. Photo: Supplied/ Susan Imrie Ross for the SBYA Awards 25

In the right key: Nduduzo Makhathini, winner of the SBYA award in 2015, left, and poet and playwright Maishe Maponya, the first black winner, above. Photo: Supplied/ Susan Imrie Ross for the SBYA Awards 25

The criteria governing who gets what, when and how remains unclear, with Sebesho saying, “We always want to do more but, unfortunately, it’s not always possible. We’ve got budgets, we’ve got competing priorities that we need to manage.”

To Khumalo’s point about artists who contribute other things to society, this year’s pair of music winners embody that prerequisite with distinction. Charles, for one, values teaching as much as she values the mentorship and comradeship that has defined her long association with the National Youth Jazz Festival.

Singer and guitarist Muneyi, on the other hand, effortlessly sidesteps all manner of boundaries with nary a whiff of contrivance. Able to command an audience with just his voice and guitar, his craft is mostly mined in intimate settings which, like much of the arts infrastructure, have been substantially diminished or altered by the impact of Covid-19.

“The music business has changed into a big-tech business and the food chain disparities have only grown bigger,” he says, via text, of the landscape he contends with.

“I think audiences were also more curious during lockdown and now there’s just a lot of 30-second noise masquerading as music.”

Among the more intrepid SBYA music winners in recent history, Muneyi is both emboldened by and reflective about the particularities of being sponsored by a corporate entity whose primary goal is its bottom line.

“The Standard Bank Young Artist Award has come with a lot of respect, especially from my peers,” he says.

Muneyi accepts his SBYA award

Muneyi accepts his SBYA award

“It took a bank to make others see me as an equal or as worth having a seat at the table but, beyond that, there’s been so much support that I otherwise would not have had, especially financially. That’s been amazing — and also being connected to a network of legacy.”

But there is also the feeling of having to pull back. “[It’s] constantly having to think about my values and those of an institution whose primary end goal is to function as a business. Understanding that my own values and beliefs differ a bit in that regard.

“For example, what does radicalism look like when one is associated with such an institution? What are the institutional beliefs on certain pressing matters? In my speaking out, what repercussions can I (financially) afford to stand for should things go south?”

The year 1985 is four decades from the present. What Muneyi’s art offers is a yardstick to measure how far we’ve come as a society. Have we turned the corner? Have we hit a cul-de-sac? Or have we come full circle?

Siya Charles and Muneyi will perform at the Standard Bank Joy of Jazz festival this weekend at the Sandton Convention Centre.

Maishe Maponya’s quotes are from his profile in the book Standard Bank Young Artist Awards, 25 Years, published in 2009 by DeskLink Media.