There are several ways West African countries can strengthen their election management, but election commissions must constantly evolve if they are to oversee elections that reflect the will of voters

(Photo by Olukayode Jaiyeola/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

COMMENT

The crass and partisan manipulation of African electoral management bodies (EMBs) was a central feature of the legacy of abuse that successor regimes to colonial rule in Africa inherited and perpetuated. Embedded in partisan politics through “outright control” by successor regimes, EMBs became what the UN Economic Commission for Africa called “ineffectual mechanisms for democratically managing diversity”.

To lay to rest the ghost of such partisan political abuse, and to nurture and strengthen trust in electoral commissions, the democratic transitions of the 1990s stipulated new norms and rules for redesigning competitive party and electoral politics and systems. These norms included democratic political succession and entrenched provisions for the periodic conduct of credible elections and, in the case of presidential systems, fixed presidential term limits, the promotion of diversity, civic participation, and engagement, especially through an increased role of civil society and marginalised groups and the establishment of independent EMBs.

Indicators of what credible EMBs and electoral integrity should look like were set out in African codes and standards such as the UN’s African Charter for Popular Participation in Development and Transformation (1990) and the AU’s African Charter on Democracy, Elections, and Governance (2007) to name just two. But has the objective of nurturing credible EMBs and electoral integrity been achieved?

Multiple management models

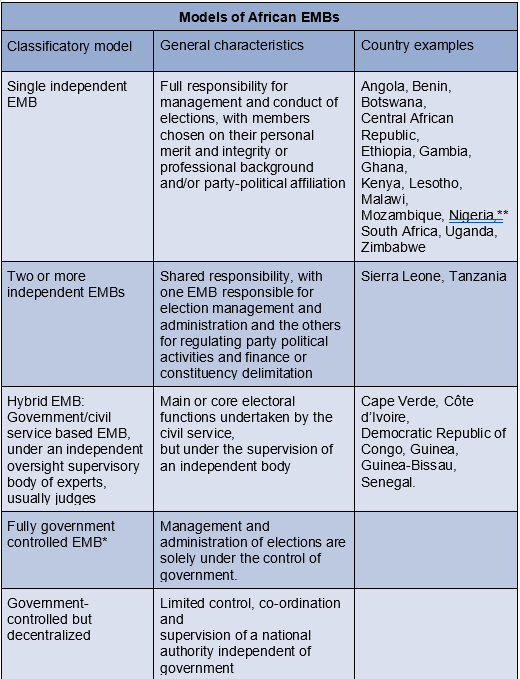

EMBs in Africa are currently either a single, independent body comprised of two or more bodies with shared responsibilities for election management, or a hybrid government-civil society EMB under an independent oversight supervisory body of experts, usually judges. Non-autonomous or fully government-controlled EMBs inherited at independence, notably in francophone and lusophone countries, have been replaced with autonomous or semi-autonomous ones. But within these classificatory models, structures and composition vary significantly, dictated by each country’s constitutional and political history, and the interplay of contending sociocultural forces and prevailing circumstances.

However, appointment processes and the tenure terms of the chair and members of election commissions are problematic areas across the continent. Concerns remain about the transparency of the nomination, appointment and removal process of EMB members according to a 2013 Economic Commission for Africa expert opinion survey. It found that “in only 10 of the 40 African countries surveyed did more than half the respondents consider the procedure to be mostly or always transparent and credible…[with] serious implications for the integrity of elections in Africa.”

Renewal under consecutive fixed tenure for members tends to enhance EMBs’ credibility, but remains problematic and is diminished by the power of appointment and renewal, which is also the power of removal. This power can be used to remove members perceived as resisting or not pliable to executive branch partisan influence, or who, by general perception, have not lived up to the integrity expectations of their office. In Nigeria and Sierra Leone, EMB members have been removed before their tenure expired. To pre-empt such a possibility, it has been suggested that the tenure of EMB members should be fixed, like judges, to their retirement age, except for cause, as is the case in Ghana.

Autonomous actors?

Recent studies of West African EMBs distinguish between their formal, administrative and financial autonomy. The level of autonomy varies not only from country to country but also within country over electoral cycles according to a 2019 study of six West African countries commissioned by the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) Network of Electoral Commissions (ECONEC). The study explored factors driving or constraining the autonomy of the EMBs and how these impact election integrity.

In Benin, the financial autonomy of the Commission Electorale Nationale Autonome (CENA) is constrained by attempts by the ministry of finance to exercise a priori control over its expenditure. This leads to dysfunctions in the electoral administration process. Another problem is the dependence of the CENA on the executive to obtain electoral funds. This challenge confronts many EMBs in the ECOWAS region. Furthermore, in Senegal, the 2019 ECONEC study found that when the funds were released, almost half the election budget was spent by the other institutional actors such as the judiciary and security agencies.

But formal autonomy on paper does not always translate into practice. In West Africa, several EMBs have almost identical legal provisions protecting their independence, yet they have widely differing degrees of autonomy. An EMB, like CENA in Benin, made up of members nominated by political parties, whatever its defects, has sometimes conducted elections with more independence and competence than an expert commission such as Nigeria’s. Cape Verde’s EMB has a longer tradition of effective performance and independence in action than Senegal’s, even though both exemplify the same classificatory model.

Although the different systems of appointment and composition do have an impact, institutional partnership and collaboration between EMBs and other institutions with election-related mandates— such as the inter-agency consultative committee on election security established by Nigeria’s Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) — can play an equally important role in shaping perceptions of EMB capability. Issues such as a country’s size, the relative balance of power among political parties, the internal security situation, and the strength of courts, the civil service and civil society, are critical for the conduct of credible elections.

In short, an autonomous EMB is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for conducting credible elections.

An anti-democratic political culture of impunity characterised by abuse of power by incumbent parties for partisan electoral gain, a zero-sum approach to electoral competition that ignites and fuels electoral violence and high levels of vote-buying and voter intimidation create an environment in which conducting credible elections is difficult, regardless of the technocratic skills and technological innovations deployed.

This is the experience in Nigeria, where controversial elections were held in 2015 and 2019, despite the popular perception of INEC as increasingly credible after it invested in technology such as smartcard readers and undertook internal administrative and financial reforms, after polls in 2011, to try and limit the space for electoral malpractice.

Advancing credibility

Enhancing the application of information and communications technology and internal administrative reforms that improve the transparency of EMBs has improved electoral transparency in Ghana and Nigeria. So too can enhancing the administrative and financial independence of EMBs.

This can be done by vesting in them powers to recruit their own staff, professionalise their bureaucracies, and make their annual budget and election budget direct charges on national consolidated revenue funds. Reforming EMBs also requires removing their members’ appointment and reappointment process from political officeholders and vesting them in independent, non-partisan individuals or bodies.

But election commissions need to be supported in their efforts to conduct credible polls. Partnerships with civil society organisations can improve civic awareness and tackle prevailing problems such as vote-buying. Allying with impartial security actors can also discourage campaign and election-day violence, while regular dialogue with all political parties can go some way to reducing the zero-sum, winner-takes-all approach to politics.

They also must continue to learn from each other. ECONEC, and the Electoral Commissions Forum of Southern African Development Community countries, are constantly sharing experiences that can shape regional best practices.

The impact of these discussions and dialogues become clear on election day, but the work to get there is ongoing and unending. Maintaining credibility does not just mean standing still. Election commissions across West Africa must be constantly evolving if they are to do their part to oversee elections that reflect the will of voters.

This is part of a series of essays exploring the state of electoral democracy in Africa that is being run in conjunction with the Abuja-based Centre for Democracy and Development