Sulyman Martin.

As a venue for our interview, photographer Nadine Hutton suggests a tshisa-nyama (braai place) in the eaves of Park Station in the inner city of Johannesburg. When I arrive she is already there, sitting on a bench, looking westwards towards Park City supermarket.

It is a few days after the opening of her solo show I, Joburg, an exhibition comprising film and stills shot on her iPhone at the rather puny space, Room, on Juta Street. That same night, two streets away, Dale Yudelman’s exhibition Life Under Democracy opened at the stately Wits Arts Museum.

Hutton is at once a regular and an oddity in this vicinity. It could be the beautiful Star Wars tattoos adorning both her arms or, most likely, it is because, as a white woman in a predominantly black space, she immediately stands out.

Although schooled in the analogue tradition of the seductive darkroom, negatives and films — apart from film processing, what else happened in those rooms? — Hutton has embraced digital photography and its most iconic poster child, the iPhone.

The device was developed by Steve Jobs, the late American icon immortalised in the acrid and self-referential tome The Map and the Territory, French writer Michel Houellebecq’s latest novel. The novel features artist Jed Martin, and Houellebecq himself as a character, as the former is preparing for an exhibition. (Houellebecq has been asked to write the text accompanying the exhibition.) One of the paintings is called Bill Gates and Steve Jobs Discussing the Future of Information Technology.

One wonders whether in this discussion Jobs told Gates how, in the future (okay, okay, in the present), the iPhone would not just be a phone (a mouth and ear of sorts) but a camera (an eye, if you may) as well.

What is clear is that the iPhone, despite its limitations, has edged its way towards being a camera of choice for those who can afford the device, even for “serious” and accomplished journalists such as Yudelman and Hutton.

“I have been using the iPhone for two years now,” Hutton said.

Formerly the Mail & Guardian’s pictures editor, the 36-year-old likes the phone because it shoots in both black-and-white and colour.

Even though it has limitations —the image cannot go beyond a certain size, the camera is not very good in low-light environments and the wielder of the iPhone does not have much leeway in terms of exposure control — one can still exploit the gadget to achieve optimal, sometimes exceptional, results.

“Like any tool, if you know how to use it you can do it well,” Hutton said. As someone trained in analogue, she is quite scornful of the lack of discipline associated with digital photography, the ad hoc shooting of multiple images. But using the iPhone is a bit like using film, her first love: “You can choose your lens and your film. You make those conscious decisions before you shoot your picture. It feels like analogue again.”

The reason why most of the images in the exhibition are in black-and-white is to mirror the project of documenting the city.

“As the city becomes grainier and grittier, it makes sense to document it in black-and-white because you lose texture when you shoot in colour. You get a cacophony of colour. Today, the digital image is so saturated with so much colour it’s almost obscene. [Besides], there is a romanticism about pictures in black-and-white, something colour doesn’t have.”

The unobtrusive iPhone has made it possible for her to walk the city quickly, capturing moments that would have been lost if she had to haul heavy-duty camera equipment that would make many wary and some perform before the eye of the camera.

“I want to capture the spirit of the place. People are always taking pictures of themselves with their cellphones and they don’t feel the need to perform for me,” Hutton said, adding: “I want to go to places where other people don’t. This part of Jo’burg is completely hidden.”

And the iPhone doesn’t attract the wrong kind of attention from bag snatchers.

The vast assortment of pictures includes one of a man standing over a forlorn knoll, perhaps fiddling with his phone, while a hazy vista of the city looms in the distant background.

Although there is a romanticism in black-and-white images, it is ingrained with a certain menace. It could be a city whose residents are waiting for a hurricane to tear through, ravaging and uprooting everything in its way.

A barefoot woman runs across a road, a grizzled poster of a clenched fist is eaten by time and chewed up by the elements and filth in black bags is strewn all over, as if a hyena, the scariest of scavengers, has hastily abandoned its prey.

Then there is the lens trained on Jo’burg’s queer scene (the exhibition includes stills of the film Memoirs of Killarney Houseboy, also shot with an iPhone).

Yudelman’s project is, shall we say, grander. Going under the rubric Life Under Democracy, it is meant to examine the past 18 years of private and public life.

Yudelman, who boasts three decades of photojournalism, is eminently qualified for this kind of work.

All-seeing and penetrating

According to the text in the catalogue, published by Jacana, the photographer “returns to the areas he photographed in the Eighties for the series Suburbs in Paradise”. As a recipient of the Ernest Cole photographic award, he visited some of the people and places the late iconic photographer shot. The question at the back of Yudelman’s mind was: “How would Mr Cole feel about the problem he dedicated his life to achieving?”

The lens of the landscape he captures is all-seeing and penetrating, trained as it is on the sad and surreal, the tragic and titillating and a lot in between that characterises that lofty undertaking of the rainbow nation. The work is varied. It ranges from the raw images shot by a photojournalist (for instance, the straight-up, in-your-face work that focuses on the newspaper posters and protests) to beautiful portraits set against ironic and puzzling backdrops.

For instance, there is an image of a man, bloodshot and red-lipped, who carries his knife scars with the pride of the scarified. There is a quartet of photographs of a man being arrested. In them you see the documentarian’s impulse to get the image, a feeling that somehow overcomes the aesthetics of the picture.

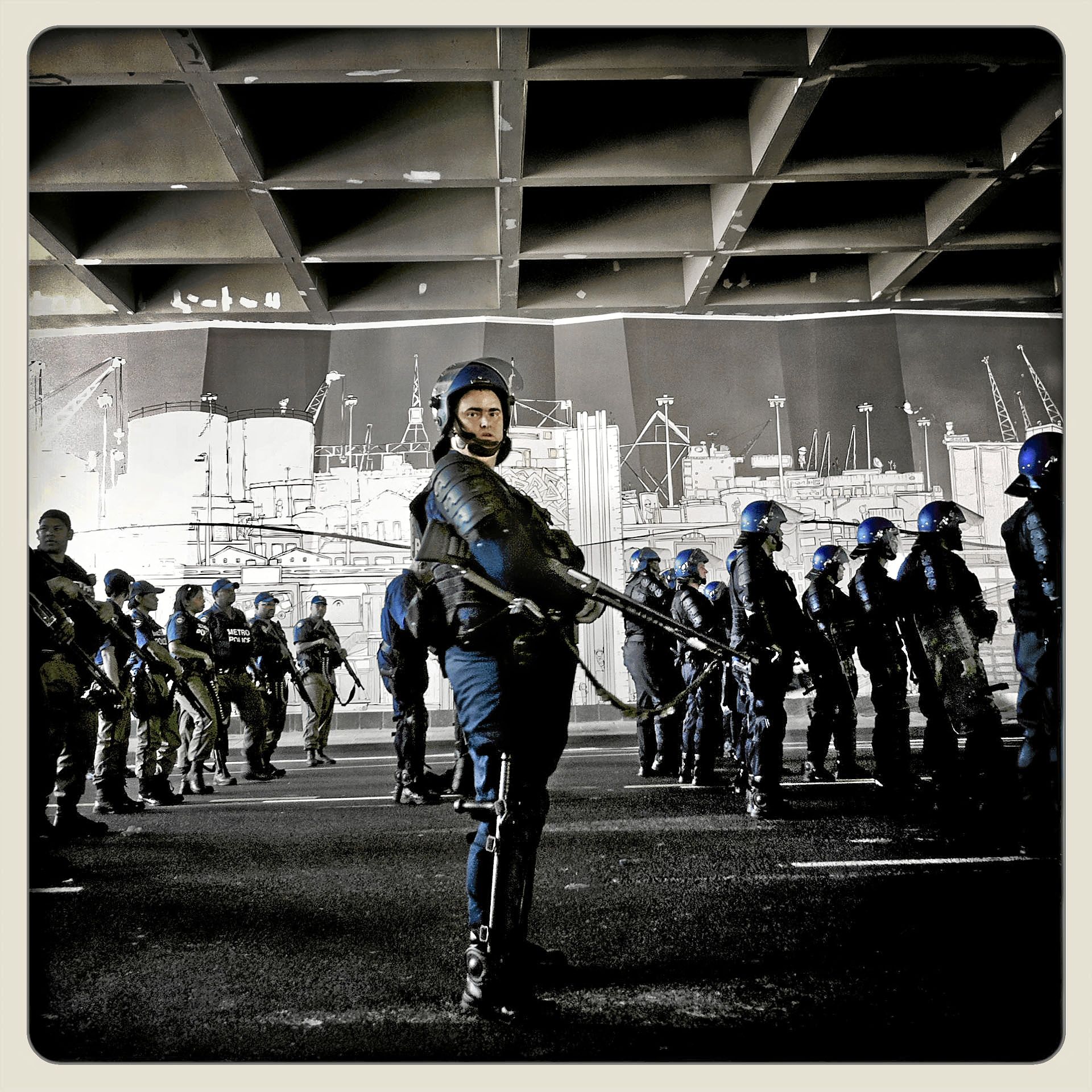

Anger and danger hang over some of the images: machine gun-toting security guards, riot police undergoing drills — even the man wielding an axe after chopping wood has the menace of a man about to slice someone’s skull in two.

Yudelman says using the iPhone has not been without its challenges.

When, for instance, he attended protests, “some of the press photographers would look at me like a tourist”. Because the iPhone can take only eight pictures at a moment, one imagines what one could potentially lose if the action becomes particularly quick and heated.

But what the iPhone takes away with the left hand it gives back with the right. There is a picture of an emaciated sex worker, her face demurely set against the wall. “If I was carrying a big camera, she would have got worried.”

If these two artists, accomplished in analogue, say the iPhone might be the way to go, who am I to argue?

I, Joburg runs at Room gallery, 70 Juta Street Precinct, Braamfontein until September 29

Life Under Democracy runs at the Wits Art Museum, Jorissen Street, until September 25, at the KZNSA Gallery in Durban from October 3 to 21 and at the AVA Gallery in Cape Town from October 30 to November 23