With Thulani Serero injured

We all know the arms deal is important, but the whole saga has been dragging on for so long, you may have forgotten who did what and why it matters.

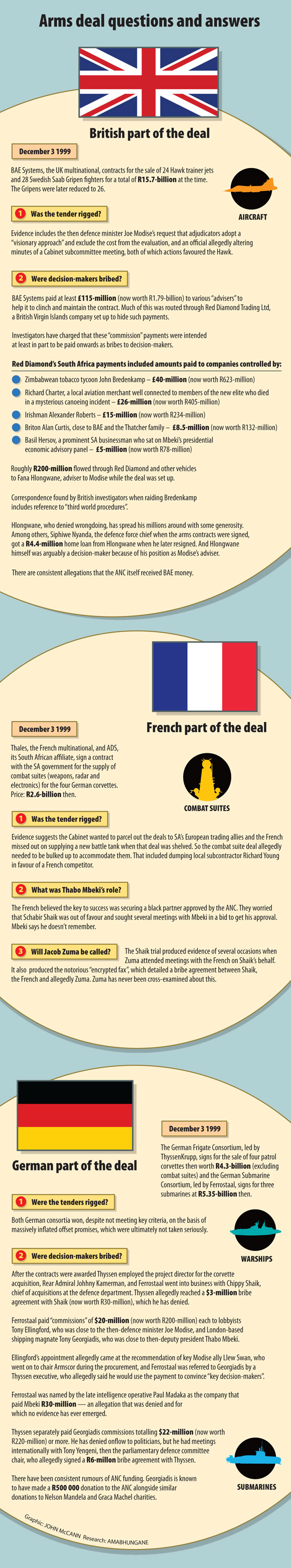

So here’s a handy guide to what we know and don’t know (see graphic below).

But first: Why we should care?

The arms deal is important because it represents our loss of innocence as a young democracy.

It’s the deal that poisoned the post-apartheid political well, and the poison is still flowing, as demonstrated by the alleged attempts of the Seriti commission to stage-manage the inquiry.

As a result the commission, which is to start hearings finally on Monday after a postponement on day one a fortnight ago, seems set to join a long line of individuals and institutions damaged by the remorseless pressure to find nobody guilty.

Pressure

Where does pressure come from?

It’s the “too big to forgo, too big to fail, too big to fall” scam.

There are people who travel the world, perfecting the art of selling cripplingly expensive white elephants: arms merchants, bankers, sports administrators and civil engineers.

Their schtick would be familiar to any street-corner con man: promise the earth, flash a lot of money around, have a complicated, expensive black box that is going to deliver the magic, make sure the victim is sucked in and compromised by the process – and then take his money.

At that stage, having “borrowed” the family grocery money or the company petty cash to get in on the deal, the victim faces humiliation or worse if he owns up.

The aim is to get him to invest his reputation as well as his money, so you can string him along while he tries to cover up and digs himself a deeper hole.

Defence companies are rightly notorious for this process, but our politicians were too arrogant and too greedy to take any notice. They fell for the script.

Too big to forgo

In the early 1990s, the navy presented a modest plan for acquiring new surface ships. As this plan had its origins in the dark days of apartheid, it was scotched by the military’s new ANC masters.

Instead, the politicians were persuaded to embrace a complicated megadeal, which threw in things the military initially didn’t ask for, such as submarines and new-generation jet-fighters. The deal was so big, it would drain the national grocery money for years to come, but that was okay, because the clincher for this “opportunity of the decade” was a big black box called “offsets”.

The weapons would cost R30-billion, but they would generate more than R100-billion in offset obligations, it was claimed.

Offsets, contrary to the normal laws of economics, would make the deal pay for itself by magically persuading defence companies to invest billions in things they did not understand or care about, such as tea plantations and condom factories.

But the black box was so complicated and secret that no one was allowed to look inside – except the worthies at the trade and industry department who had staked their reputations on how well it was going to work.

No wonder, then, that we had to wait years, until those obligations were “fulfilled”, before government let us look inside the offset box and see the magic was all cardboard cutouts and clever lighting.

Too big to fail

Sellers of elephantine projects know that the bigger and more critical the deal, the more national interest and prestige is involved, and the more “big men” have engaged their vanity and lined their pockets, the harder it will be for anyone to stop the juggernaut, or even impose any discipline or accountability after the fact.

So the salesmen will discourage the consideration of engaging several competing suppliers of a proven if unexciting design (of, say, power stations), but rather suggest one monster deal involving all sorts of “cutting-edge” technology, backed by terrific “economies of scale”.

This, of course, allows everyone, from contractors to workers, to leverage the opportunities for blackmail thrown up by the “too big to fail” scenario.

The buyer has little choice but to allow the goal posts to be shifted and to pay up … and he risks finding himself with technology that he cannot afford to run or maintain.

Thus it was with the arms deal.

Those Gripen jets are mothballed, those subs are mostly dock-bound, those corvette propulsion systems are faulty, those choppers are mostly grounded.

Too big to fall

Because arms deals tend to be legally, ethically and politically controversial, defence companies have learned that tying in political and institutional heavyweights, such as the head of state and the ruling party, is important not only to clinch the deal, but also for insurance when awkward questions are asked later on.

The companies use middlemen for the nasty bribery stuff, but are themselves adept at delivering a softer blanket of schmooze: sponsored “fact-finding” joy-rides, car discounts for officials, jobs for ministers’ children and generals’ wives, building a “special relationship” with the minister of defence, offering donations to the president’s pet projects – and, of course, to the ruling party.

All these techniques were on display in our arms deal, though their full extent is only indicated by the size of the commissions paid to middlemen and the political ferocity with which the deal was protected.

It almost doesn’t matter whether anyone was bribed; what matters is that we were so stupid that we fell for the con and then spent the next 15 years defending it.

Worse still, we have not learned the lesson.

We still fall for those peddling mega-projects to solve our problems: from the overpriced stadiums of the World Cup and the nightmare that is Medupi to the truly scary prospect of a trillion-rand nuclear power station fleet.

If the Seriti commission can puncture that hubris just a bit, maybe it won’t be a complete failure after all.

This piece was originally published on August 15 2013.