One of Sheldean Human's classmates at her memorial. Sheldean's body was found in a stormwater drain 15 days after she disappeared in February 2007. Andrew Jordaan was sentenced to life in prison

Trigger warning: some readers may find below content and images traumatic.

When I was about five years old, I was sexually abused by a stranger. I don't think at that age I really understood what it was that had happened to me, but somehow I knew it was wrong, and I felt to blame for letting the man touch me.

Shortly after the incident, I told my parents. I cannot begin to imagine the weight my disclosure must have had on them: the grief and the rage, furious at themselves for failing to protect me, enraged at the man for doing this to me, and infuriated at the world for allowing this to happen to their young daughter.

The molestation could not have lasted more than a few minutes, but it affected my life in ways that are difficult to articulate.

As a five-year-old, I don't think you really understand that you have lost something when you are abused. Yet you have; something does change. You lose your childhood, really: your innocence is snatched away, and what little is left of that once pure child is now transformed into a sexual being, a child with a knowledge of things way before her time.

My Piece of Sky is the result of the journey that has since led me to explore the world of child sexual abuse. It is testimony to the young children who have survived the experience of rape, and those who have lost their lives to it.

When children are molested or raped, they lose control over what is happening to them and their bodies, so when working with victims I was sensitive about giving control back to them. I would generally begin by sitting on the floor in a corner or somewhere out of the way. Once in my spot, I would move very little. I would take few photos, watching to see how the children responded to the camera. I would interact with them often, becoming part of the team that worked to comfort them and make them feel safe.

When I interviewed the perpetrators, it was with the understanding that My Piece of Sky would take some time to complete, and that they would not be identified, so as not to influence any pending court cases.

My interviews with them were really motivated by my need to understand their own childhoods, when they were first attracted to children, whether they were abused or not, how they chose their victims, how they went about abusing them.

My work with perpetrators threw me into a deep depression – but not for the reasons you might think. The truth is, we all have multiple facets to our personalities and these perpetrators were no different. They were abusers of children, but some of them were funny, intelligent, creative and interesting.

After attending their group sessions for several weeks, one of the perpetrators asked me in front of the group how I felt about them now. "Do you think we are all monsters?"

I didn't. I could not at all condone what they had done, but I did not hate them. With this discovery, my black-and-white world of right and wrong, good and evil, caved in on top of me.

Ten years later, I am not the same person. Not because I have aged, but because I have learned so much – too much, really.

Meeting these people and hearing their stories has taken me to the limits of my psychological, emotional and spiritual existence. It has tested me in ways that I am not yet able to comprehend. After many of the interviews, I would lie on my floor for hours, in shock from what I had heard.

Many times I have wanted to lock these interviews and photos up and walk away from them, pretend I had never heard them or seen them.

Only a sense of obligation to those who shared their deepest, darkest secrets with me, so that it does not happen again, has prevented me from doing so.

Jennifer (13) sits in a police car after being rescued during a night raid. Abducted in Durban, she had been brought to Johannesburg and forced into the sex trade. She said she had not been made to work yet, but that her handler and another man spiked her drink and raped her.

Profiles of the abused:

Dylan

My name is Dylan and I am 39 years old … At the time, John taught at a school near me. He was a scoutmaster and our catechism teacher at church. So I knew him and I trusted him. When I was with Creasey and he was doing things to me, I would not hear a thing; everything just buzzed in my ears and I would not be there; I escaped to another place inside myself. He would reward me if he could touch me once or twice. It depended on how many times he could touch me, and that is how much of a reward I got.

I confessed every week, or every time it happened, to the priest at church. I would say to him that I had been touching a man and that a man had been touching me, and he would just tell me that for my penance I needed to say so many Hail Marys and so many Our Fathers, and try not to do it again. That only reinforced my feeling that I was in the wrong and that it was my sin.

When I was 13 I made a decision that I would make men pay for it from now on, that they were not going to take me for granted. I mean, they were taking me anyhow, so they are not going to take me for nothing anymore. Whoever wanted a boy like me had to pay for it. There are images out there of me that I know can never be destroyed; they are there forever. Having my photo out there is basically like being raped every day.

Dylan committed suicide on April 23 2008.

Inspector "Stroppie" Grobbelaar struggles to tell Anna Lesele, the aunt and adoptive mother of Kamo, that his search team has still been unable to find her. Grobbelaar stops at her house in Eldorado Park, Johannesburg, every day with an update.

Thuli

My name is Thuli and I am 27 years old … I was six at the time of the incident and that day I was actually sick. My father was not working. At some point, he came up to me and told me that he was "not going to feed a horse if he was not going to be able to ride it", and he pushed me on top of the bed, tore my panty off, put a pillow on my face and started raping me. I didn't cry because I didn't understand what was going on.

My mother came home and she saw that I was bleeding and took me to the Randburg Police Station, and then to the doctor to confirm the rape. The doctor told my mum that yes, I had been raped, and they took tests and stuff. Nothing happened.

After the first incident, the rape continued. It just never stopped. My father would rape me in front of my mother. He would sleep with me in front of my mother and I would hear my mother crying.

When I was 14, I found out I was HIV positive. When I would think about killing my father, there would be this calmness that would come over me.

I am usually scared of corpses, but that day I was not scared. I just wanted to see this lifeless body and know that he was really dead. So they took me in and then they opened this drawer and my father's eyes were open. I asked the guy if I could have five minutes alone with my father. I stayed there and I talked to the corpse. I said: "I am not a murderer, but you pushed me so hard. I didn't have any choice …"

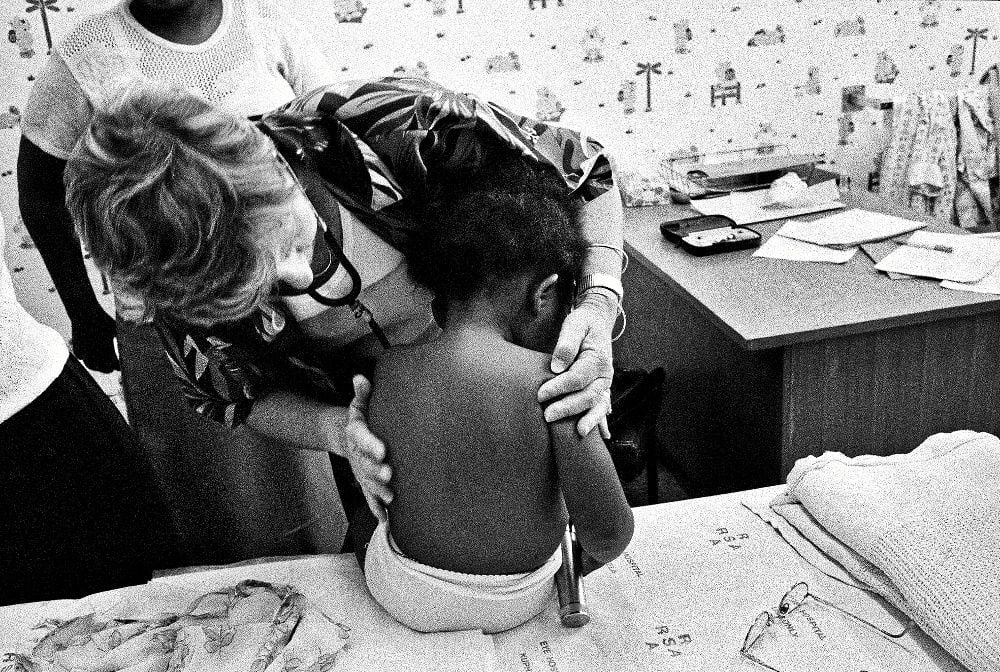

Professor Lorna Jacklin, a neuro-developmental paediatrician and director of the Teddy Bear Clinic for Abused Children in Johannesburg, begins a medical checkup on a sexually abused two-and-a-half-year-old girl. Asked to lie down for the medical check up, the toddler lay back and spread her legs as she had been trained to do by the perpetrator.

All photos courtesy of Mariella Furrer. To view the full body of work go to www.mypieceofsky.com. To view the video interview with Mariella, which goes live on Monday, please visit mg.co.za/mariella.