My idea to walk Johannesburg's infamously polluted Jukskei River sank almost as soon as I decided to do something about it. When you become determined to walk the length of a river there's really only one decision left to make, and that's where to start.

For pointers I had just read Peter Ackroyd's vast 2007 tome Thames: Sacred River, in which he announces that "the journey towards the source is the journey backwards, away from human history", and although that sounded like a valid advisory the opposite, of course, is true in the case of the Jukskei.

The source of the Jukskei is more or less in the centre of Johannesburg, and it runs out for about 50km to join the Crocodile River just beyond the city's northern reaches.

This radial neatness in a city in which so little is straight, planned or makes immediate sense suggested to me that it hardly mattered in which direction I travelled – whatever the walk was going to unlock would be unlocked equally either way, and as much on the east bank as the west.

But in the end the thought of the Johannesburg skyline looming before me always as I trudged, like a giant Guy Tillim print I wouldn't be able to take down, was completely unacceptable.

So I took a room for a month in the Troyeville Hotel, across the valley from Doornfontein, the suburb in which the Jukskei is said to rise.

Almost immediately I faced some far more daunting obstacles.

Money had briefly returned to the once luxurious suburbs around Ellis Park ahead of the 2010 football World Cup and the hotel, for years the dingy last outpost of old-town intellectuals, had suddenly found itself a safely edgy venue for company Christmas parties and low-profile book launches.

In my first week there Tim Butcher turned up, fresh from a 500km tramp through the jungles of Sierra Leone, about which he had written a book.

His previous effort was Blood River: A Journey to Africa's Broken Heart, an account of his trek down the Congo River.

As the anecdotes about murderous militias and man-eating crocodiles mounted, the Jukskei started to seem like small beer.

I had, furthermore, failed to locate the river's eye. The maps I had to hand indicated the Jukskei started either at Bruma Lake or a little to the south of it, at the bottom of Bezuidenhout Park, several kilometres short of Doornfontein.

Searching for the eye

When I visited the Johannesburg City Library in search of clearer orientation, I had found the doors barred and a notice declaring a year of renovations. The city seemed reluctant to give up even the most basic facts about itself and so I killed the project, lived out my month in the hotel and moved to Cape Town.

Two years later, I was back. The books in the Africana section of the Johannesburg library were still in boxes but a benevolent librarian indicated I was welcome to take pot luck and led me to the box that, she felt certain, contained the literature on Johannesburg.

That morning produced some promising co-ordinates. The first clues came from GR Allen's 1994 thesis on the subdivision of the Witwatersrand farm of Doornfontein, or Doren Vontijn, which contained a copy of a report submitted in 1853 by the farm inspection commission of the Transvaal Volksraad. This confirmed that the farm was "served by one spring", which was located near its northern border. In 1861 ownership of Doornfontein passed to Frederik J Bezuidenhout, who sold the northern portion to his son, Frederik Bezuidenhout Jr, who in turn, in 1891, sold 45ha of his farm to the Johannesburg Waterworks Exploration and Estate Company. Company chief James Sivewright hoped the 18 000 litres-an-hour flow rate of the spring arising on this portion of Doornfontein would be sufficient to supply the exploding city with water, and ordered that a waterworks be established next to it, "halfway up what is today Sivewright Avenue".

I took a taxi directly there and found plenty of sewage running down the road's mid-section and into a drain eyelid, but nothing to suggest the presence of an artesian spring. Wendy Bodman, the ardent water- quality activist who in 1981 penned an invaluable booklet called The North Flowing Rivers of the Central Witwatersrand, perhaps experienced something similarly discouraging, for she declared the eye of the Jukskei "irrevocably lost beneath the development around Ellis Park".

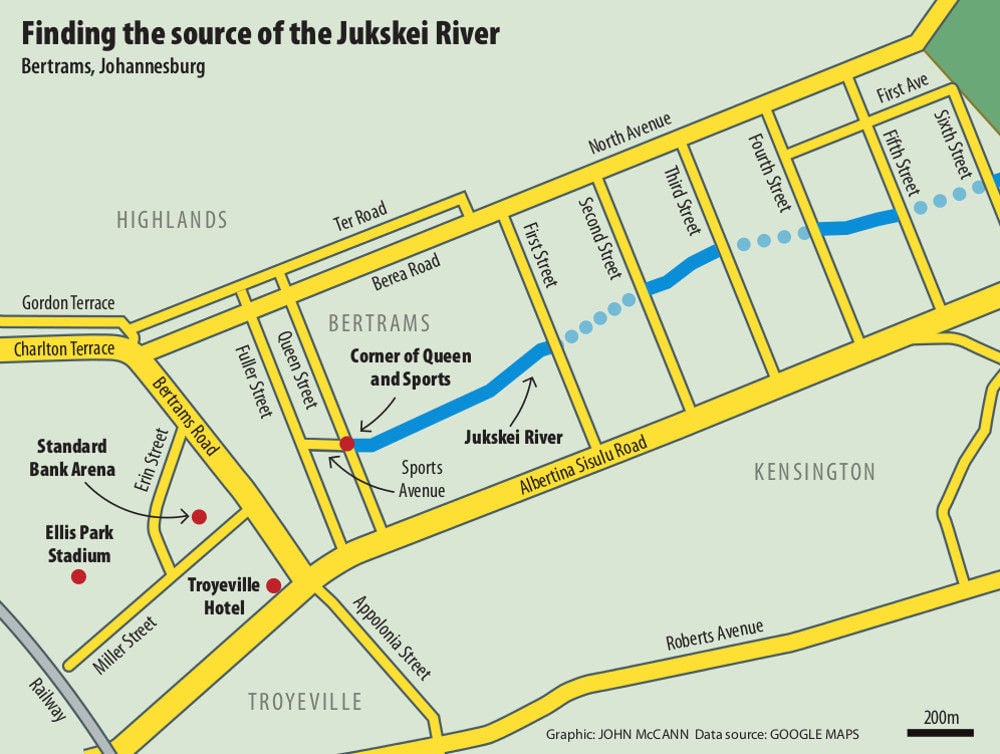

Feeling stumped, I called water heroine Mariette Liefferink, Johannesburg's very own Erin Brokovich, who put me in touch with the equally outspoken Paul Fairall, chairperson of the Jukskei River Catchment Forum, who said he believed that the source of the Jukskei lies under the Standard Bank Arena in Bertrams.

The next morning I was outside the tennis courts of the Gauteng Central Tennis Association at 7am to meet Phillip Siyeti, the arena's caretaker. When Siyeti arrived he recounted how, when the facility was being developed in 1986, the builders "pumped and pumped" but could never get the water clear; they would come back the next morning and it would be waist-deep again. We were standing in the gloom of the internal walkway, staring into a deep water-filled well out of which snorkelled a series of pipes.

The Jukskei River meanders through the suburb of Bertrams near Ellis Park in Johannesburg. (Madelene Cronjé, M&G)

"I listen to the tiles every day," said Siyeti, of the tiled concrete slabs that cover the arena's two wells. "If I hear the pumps have stopped I know this place will be a swimming pool in one day." But Siyeti was also convinced that, pre-development, the Jukskei would already have been flowing by the time it reached this point.

"The water comes from the direction of the Ellis Park swimming pool, which is nearby, a little way up the hill. That is the start, I think."

A day or two passed in which it seemed as though I was rattling around in the brain of an amnesiac.

A spokesperson for Aveng Grinaker-LTA, the company that developed Ellis Park in the late 1920s, emailed to say their records did not extend beyond a few decades back.

A jaundiced long-term employee in the Johannesburg municipality offices in Braamfontein said much the same thing of the city's records: "When things changed politically [in 1994], almost all the municipal minutes from before the 1990s were thrown out, because the new guys saw it as Afrikaner stuff."

It would be better to search for the finer points of the city's history among the living, it seemed, in men like burly Gus Malgas, who has worked for the city for three decades and is currently its "aquatics manager for region 8".

Malgas conducted me around the series of sky-blue swimming pools that lie in the shadow of the Ellis Park Stadium, which is to say upslope from the tennis arena, downslope from the rugby grounds. We paused by the diving well, a deeper azure than the other pools because of its 5m depth.

"I have not put a hosepipe in here in years," he said. "All pools lose water through evaporation and micro-fissures in their foundations, but these actually take on water from the ground around them."

The fact that the incoming water is crystal-clear supports his belief that the pools are sited over the Jukskei's eye, though Malgas felt compelled to say that Joe van Staden, who maintains the Ellis Park rugby stadium, would tell me differently. Twenty minutes later I was standing with the equally burly Van Staden on the side of the field made famous by Joel Stransky's 1995 World Cup-winning drop kick, staring at a pipe near the corner flag out of which water flowed at roughly the rate of a fully open farmhouse faucet. The Jukskei, he told me, starts right there.

The swimming pool at Ellis Park could be the eye of the Jukskei River. (Madelene Cronjé, M&G)

Van Staden's claim had a certain hydrological logic to it though, the rugby stadium being upslope from the other possible sites, and considering the matter closed I made plans to begin my journey down the Jukskei.

Word moves fast in Johannesburg, though, particularly among the small clique of young developers who drive the various fronts of "inner-city renewal", and that night I received a call from a guy, who asked for anonymity, who said my search for the river's source was not complete. He gave me an address, the corner of Beit and Height streets in Doornfontein, and told me to be there at noon.

From the parking lot of the Doornfontein McDonald's the next day, I squinted up at the signage atop the veritable Carlton Centre-on-its-side before me. "Die Vaderland" read the wraparound signage, and the penny dropped: this hulk was the old Perskor building, the one-time headquarters of the state-controlled media juggernaut.

The developer came around a corner in a hard hat, wearing the most exquisite Italian shoes. The building, he said with patent fondness, had been grotesque before he flipped it. No electrical light had burned inside it for years and scores of squatters had made their middens on the upper levels – though not in the basement, which had been pitch- black, crowded with old printing presses and flooded to above knee height. The source of the water, he maintained, was a well in the corner of the basement, which "bulged with crystal-clear water 24/7".

We entered to find sunlight streaming into the vast interior from newly torn openings – the property now belongs to the University of Johannesburg – and the printing presses long gone, leaving behind brutalist reflections in a thin skin of water on the basement floor. The "bulging waters" had been reduced to still pools by contract plumbers, but there was no doubting that the basement wells had been designed to control a spring. Given the fact that the address is upslope from the Ellis Park Stadium, no more than 100m from Sivewright Avenue, I was convinced I had found the Jukskei's eye.

Entering the canal

So the next day I stood for some time at the intersection of Queen Street and Sports Avenue in Bertrams, where the waters of the Jukskei emerge above ground for the first time, blue-grey, as though someone had been washing a pair of new jeans in the storm drain that leads back to the Ellis Park swimming pool. I was admiring the odd beauty of the scene – dozens of stream-picking sacred ibis, the impressive stonework of the canal, an Amazonian overhang of trees – when a woman called out from a second-storey balcony of nearby Carr House, a dilapidated 1950s apartment block and the source, judging from the strong flow of water into the street from its atrium, of a fair percentage of the pollution in the headwaters below me.

"What you doing, sweetie?" she asked, shaking an incredible mane of brown hair and holding a mug of beer aloft with a stick-thin arm. It was about 9am. I said I was thinking of climbing into the canal and she yelled "hang on" and disappeared inside, only to reappear on street level, along with six or seven other early-morning boozers, all of whom followed her over to where I was standing.

"My chick died in there," said a man with yellow eyes and a rime of white around one nostril. "Sis," he yelled back to the entrance of Carr House, "wanne' het Susan-hulle verdrink? [when did Susan and the others drown?]" 1981, came the reply.

A large sign next to us warned "any person, especially children" not to enter the watercourse. "This is a dangerous flood risk prone area BE careful!! Water is dangerous. Running water is more dangerous. Fast flowing storm water is deadly!!" It was dated 2004, the year three Bertrams boys happened to be messing around in the canal when it surged. Their bodies were found several kilometres away, in Bruma Lake.

It had been a dry summer, however, and it was a clear day.

"How do I get in?"

"You go around the sign and through the fence," said the wild-eyed one who looked like a junkie. "When you reach the edge of the canal, you swing off the pipe going across there and put your feet on that ledge, where you see those three Panasonic batteries."

I started off, watched with much interest from the bridge and followed by another shout from my beer-sipping Rapunzel.

"Don't step in shit," she said.

I could not decide whether it was a warning or a judgment passed on the entire mission, but I was out to see the world in a grain of sand, heaven in a wild flower and Johannesburg's scarred soul in a half-afloat Amasi container, so it hardly mattered that the going would be prosaic. It wasn't long before I had flowers looking in over the edge of the canal top – the lilac and white petals of cosmos plants, and the tubular yellow bells of the khakibos. And where the canal gave way to the river proper at the foot of Bezuidenhout Park I found my grains of sand, too – billions of them, forming a bank like a Seychelles beach.

Meeting Jukskei expert Paul Fairall a little further on in the restaurant of a Bruma Lake hotel, I described these graces with enthusiasm, a mistake I would not make again. Jo'burg's celebrity invasives, as Fairall described the cosmos plant, the blackjack, the khakibos and the castor oil bush, had in all likelihood first sprung from the banks of the Jukskei in Bez Park, which had been used as a remount station by the British army during the South African War. The white sand was courtesy of the Portuguese residents of Troyeville and Bezuidenhout Valley.

"They're great renovators, the Portuguese, and when it rains the building sand washes into the drain eyelids and ends up in the river, where it becomes saturated with raw sewage from the city to form something called organic sludge," he said.

I continued on from Bruma Lake into Gillooly's Farm, dizzy with information. I realised there was simply no way I would be able to narrate the river at a tolerable pace. I would have to approach this thing in another way, become something else, become … a golf ball.

Following a golf ball

Which is how I arrived on the seventh tee of the Glendower Golf Club, where the Callaway dropped into the Jukskei River, which runs alongside the western edge of the course.

A young, paunchy golfer, whose surname connects to a turn-of-last-century mining magnate, grunted: "No point looking for that", and his mates added: "Not unless you want to catch Ebola."

It had rained recently and urban floodwaters had coated the river banks with garbage: two flanking rivers of brittle plastics for the grey waters of the real one. In the still swiftly flowing waters, the golf ball began travelling on sandy underwater paths soaked through with organic sludge from Johannesburg's 410km of leaky sewerage piping.

The ball travelled through the grounds of the Sizwe Tropical Diseases Hospital, formerly the Rietfontein Infectious Diseases Hospital, where an 8 000-unit housing development is scheduled to disturb the graves of about 7 000 tuberculosis, leprosy and bubonic plague victims buried there, not to mention the bones of livestock brought down by anthrax, the spores of which have spent a century in stasis waiting for just such a disturbance.

The impervious Callaway continued on down to Lombardy East, where Shembe prophets on all fours vomit river water on to the embankments. It dribbled past the cliff-hanging shacks on Alexandra township's west bank, where the "woerr, woerr" sounds are plastic shopping bags being swung riverwards, weighted with night soil.

When the rains ceased the Callaway was crouching below a muddy riverbank in Buccleuch, Johannesburg's very own Pacific trash gyre: a place where polymers congregate secretly among rocks and in the overhanging branches of silver birch trees.

When the river next came down in spate, the first of its 34 annual flash floods, the Callaway streamed quickly past the Jukskei's confluence with the Modderfontein spruit.

It shot under the brutally tall N1 bridge, where "Steven is a good screw – 3 Nov 1984" is recorded, and under the Old Pretoria Road bridge, built in 1933 to resemble a yoke pin or jukskei, because it was here that an early Johannesburg settler discovered a yoke pin in the stream – all that remained of a transport wagon carried off by floodwaters.

In the late 19th century and first half of the 20th century nobody had a bad word to say about the Jukskei, which was referred to as the Yoke-skei until the 1930s. Its clear waters had slaked the thirst of the first settlers and watered the city's first gold mills. Its banks were sought out by picnickers and recommended to tourists.

In 2013, however, the Jukskei has become the city's open gutter and sewerage sluice, its blackjack-infested banks a refuge for the homeless, the criminal, the serpentine.

Private and commercial property owners along its upper reaches have turned away in fear and disgust, blocking out the eyesore with high walls and electrified fences.

Repeatedly, as I made my way downstream, I wondered what anomalous lost thing might more relevantly lend its name to Johannesburg's major north-flowing river in 2013: the headless goat slung over a low-hanging willow branch in Sunninghill? The expensively framed still life of flowers in a pitcher in among some reeds in Kyalami? The two-litre Amasi container slipping between some rocks in Buccleuch?

Finding Steven Baloyi

Then I stumbled upon Steven Baloyi. I found Baloyi on a walk that had taken me past the Leeuwkop Golf Course and the six-fence fortress of Leeuwkop Prison's C-max facility, where dassies perched on the prison's arris overlooking a series of rapids so powerful they send up soapy updrafts.

We were both startled, because it was a wild part of the river where Makro cards, lipsticks and antihistamine pop-packs are emptied into rocky crevasses from stolen handbags, and where colourful cable casings carpet the ground under dense stands of brush – the leavings of the copper cable thieves that prey on the nearby Gautrain line.

Baloyi was sitting under a willow, scouring a golf ball using river sand and a bit of a greengrocer's bag. He had already polished several balls and set them out in Pac-Man fashion on an old edition of the Daily Sun.

"The golf balls come down in the river," he explained. "I walk in the river looking for them, from Heron bridge as far as Buccleuch."

This is a distance of approximately 20km. It had taken Baloyi two days to get halfway, and in that time he had found 32 balls, which he expected to sell for anything between R100 and R130 collectively up on Cedar Road, which passes the luxurious Dainfern Golf Estate.

Tossing some stale bread pieces into the river to feed his "friend", the large catfish living in a hole below the willow's roots, Baloyi explained that he used to work as a caddy on some of the city's most prestigious golf courses until more and more golfers, whom he called "bosses", began opting for golf carts. On Wednesdays, Saturdays and Sundays, the major golfing days, there were increasingly too many caddies for too few bosses, and rather than fight to carry another man's clubs Baloyi started scouring the city's waterways for their lost balls.

"There are many of us; I can't even count them. We call ourselves the golf-ball hunters," he said.

Riverside: A golf estate stands as a fortress on the banks of the river into which singer Steve Hofmeyr once threw his U2 tickets to protest the band's stance on the "Kill the Boer" song. (Madelene Cronjé, M&G)

I suggested that he was more of a prospector than a hunter and told him about Pieter Jacob Marais, who is credited with discovering gold in the Witwatersrand in 1853 at a site on the Jukskei no more than a kilometre from where we were sitting.

Marais had been among the San Francisco forty-niner gold prospectors before returning to South Africa to pan the little rivers of the highveld.

"Did he get rich?" Baloyi asked.

"No. He didn't realise the gold was coming from upstream, from the reef, so he continued to look for gold downstream, in the Crocodile River."

"That was unlucky. He should have realised that things wash down in the water, not up."

Baloyi's's luck, if one could call it that, was also running out. It used to be that the 300ha Dainfern Golf Estate, Johannesburg's iconic northern suburbs residential security park, enclosed the only part of the river he was not able to access. Now a nearby development called Steyn City and another named Waterfall City are both rising fast upstream and downstream from Dainfern and, at 900ha and 2 200ha respectively, they restrict access to a great deal more river frontage.

"The security guards in Steyn City threaten to beat me if they find me in the river, so I have to walk around now. Eish man, I walk and walk these days," said Baloyi.

I asked him whether I could take a golf ball as a token to remember him by, and produced R50 in payment.

His hands trembled.

"Thank you very much, and God bless you. Thank you very much. Maybe choose two? Maybe take this one," he said, handing me a polished Callaway.

Traversing Dainfern

I had it in my pocket when I reached Dainfern Valley, just off the R511, and found my way blocked by a tall electric fence that stretches across the river.

An anarchic spirit streamed through me, because from Bertrams in the city centre, where the river first appears above ground, I had walked kilometres in canals notorious for their killer flash floods and skipped across the feet of grand old Johannesburg estates. I had bundu-bashed through bamboo stands in Buccleuch, trespassed unwittingly through the Leeuwkop prison grounds, been shocked by electric fences, chased by dogs and, worst of all, had at times been forced to remove my shoes and socks and walk in the disgusting river with bare feet. So fuck you, Dainfern Valley, I thought – I'm coming through.

I slipped under the fence and strolled on paved paths across manicured embankments. At the limits of Dainfern Valley I hit the far more businesslike perimeter of Dainfern Golf Estate, which was covered by CCTV cameras. I realised I'd have to get wet to circumvent this fence, but before I could take off my shoes and pants a guard spotted me and barked into his radio, summoning a division of golf carts bearing more guards in Kevlar vests. I was transported to Dainfern's administrative offices to confront Alfred Steyn, security manager and jobsworth extraordinaire.

"You must please understand from our side, Mr Christie, that we can't just have people walking in," he began politely, in answer to my long spiel about how the river was once a highway for Stone Age and Iron Age men and women, and today remains a refuge for Rastafarians, Zionists and the 200-odd Basotho men who have settled on the river bank in Kyalami, making half-metre-high shelters out of plastic bags and cooking their food in blackened paint tins, all so that they can be close to the construction jobs tossed out by the rising security estates of the northern suburbs.

"Letting me pass is your duty as a citizen of Johannesburg," I concluded, "because this river is our great repository; it belongs to us all."

Seeing him unmoved I added, a little feverishly: "And of course this is the very same river into which Steve Hofmeyr threw his U2 tickets to protest Bono's comments about Julius Malema and the singing of ‘Kill the boer'."

"Mr Christie," said Steyn, "even if you try this stunt at night, you will be detected by our thermal cameras and arrested."

He had his guards turn me loose on veld-bitten Cedar Road and like Baloyi and his fellow golf-ball hunters I began a long, parabolic walk around the fortress walls, in search of the river.

The Jukskei, which is the prize selling point of Johannesburg's most ostentatious housing estates, has a very different set of meanings in Alexandra township, also known as Alex, some way upstream.

Fighting for freedom

The story of Santo Mbongenseni and Jabu Mabela is instructive: Mbongenseni is a Rastafarian and his friend, Mabela, is a traditional healer, and for many years they lived on opposite banks of the Jukskei River where it passes through lower Alex, though nowadays they no longer do.

I first met Mbongenseni in 2010. I was morbidly staring at a large dump of animal skulls on the river bank from a pedestrian bridge between the east and west bank, when a slender man with greying dreadlocks shouted: "Disgusting …these people have no respect."

This connection developed into a conversation about the river, about Mbongenseni's fight, going back to 1995, for a space on the east bank where he and his fellow Rastafarians would be free to practise their culture. The cow heads, empty-eyed and stripped of their meat, symbolised failure, as did his shelter – a structure of wattle branches in a nearby wattle stand, wrapped up in a truckie tarp.

Retrieving a few handwritten pages from his pondok, Mbongenseni led me back across the bridge to a compound of structures neatly fenced with fountain grass and shaded by some tall silver poplars. The contrast of this carefully tended space with the haphazardly built shacks spilling out from the nearby informal settlement of Chwetla was pronounced, though the compound dwellers were clearly dirt-poor too.

"This place belongs to my friend, Jabu Mabela, the famous traditional healer, who has been in this area before anyone else, even before me," Mbongenseni had said back then.

Mabela's "surgery" was situated in the far right-hand corner of the paved compound. It had a glass sliding door for an entrance and steps at the back leading down to the river. A chalkboard nailed to one of the shed-like houses advertised his services.

- Ditaoloa (throwing the bones) – R200

- Balwetsi (sickness) – R550

- Motse (home protection) – R1 100

- Othsha serete (bad luck) – R1 500

Sitting amid the healers' props of his surgery – a conch, a candle, the soapstone bust of an African patriarch – Mabela, who was small and perhaps 50 years old, recalled the night in 1984 when his ancestors visited him in his shack off 12th Avenue in old Alex.

"They told me they were disturbed in their visitations by the number of women sleeping in the area, and then they led me out to this place by the river. It was really wild, just grasses, and I was afraid – but I did as the ancestors instructed and soon people were coming to see me in numbers. For six years I was alone here, and then the Rastafarians arrived on the other side of the river," Mabela recalled.

Mbongenseni explained that he and several other Rastafarians had left old Alex, which extended only as far as London Road to the south, for similar reasons.

"We were looking for a quiet place to build our tabernacles and found our gardens," he said.

Rastafarians maintain well-kept vegetable gardens fed by the Jukskei River near Alexandra. (Madelene Cronjé, M&G)

The east bank of the Jukskei might not have struck many as a promised land, but for Mbongenseni it was lovely. Even the defunct 1912 sewerage works in the riverbed below looked picturesque in the evening light, when black-headed herons would go wading in the sedimentation tanks. Plus a maze of Spanish reed made the river bank the perfect place to cultivate the sacred herb, sales of which, pushed into matchboxes, became the Rasta settlement's economic foundation. For four years the Rastafarians lived up above the east bank undisturbed, until 1994, when the scrapping of apartheid settlement laws caused city township populations to explode.

"Our experience of the new South Africa has not been a good one," Mbongenseni had said at the time, handing me two handwritten pages – a letter addressed to a human rights lawyer, recounting how "de Rasta Settlement Village was invaded by squatters from de nearby township".

In 1996 the Sandton sheriff ordered both "de squatters and de Rastas to move, but whereas de squatters were relocated to Diepsloot … we explained to de authorities about our culture for which we had been practising in de area, and we were promised to be relocated to de same place provided dat we make way for development."

The Alex Rastas moved closer "to de river Jukskei", where they found that "de living was extremely unbearable: children suffered colds in winter and dangerous mosquitoes in summer. Moreover, de place was hazardous because there was no clean water, no sanitation and de shelters we had created were not strong enough to stand de floods and bad weather conditions."

The settlement was razed in 1998, 2000 and 2002, and each time the Rastas rebuilt it closer to the river bank.

Returning to Alex in 2013, I found that the "squatters" had built right down to the river's edge, in among a delta of leaching trash heaps through which pedestrians walked on a system of planks. I crossed the river to ask Mabela what had become of his Rasta friends, only to be told that the healer no longer lives there.

"He was allocated a stand in Ivory Park, where he stays now because there is electricity and water there," said a woman living in Mabela's compound.

Returning to the river path on the east bank, I ran into a dreadlocked man carrying an outsized caricature of a spear, like something from a school play, though made of very real welded and sharpened metal. He directed me to a narrow alley between shacks, beyond which the river bank opened up into rows of lettuces so green and bright with droplets of water that they too seemed part of the plastic garbage spill. The well-kept garden enclosed a two-storey wooden home, which looked like the bridge of an old trawler. A tabernacle had been established further down the river bank, the cleared circle planted with a tall post on which the red, green and gold lion of Rastafari slumped for want of wind.

"You are back," said a soft voice and it was Mbongenseni, just returned from a memorial service "for one of ours, stabbed to death last week in a fight with his neighbours over electricity". "These people," he said, "have no love for Rasta."

Mbongenseni explained that the garden and the rickety house belong to his friend Tosh, and that the 30 or so Rastas remaining in Alex "are now relying on him to defend our place".

Mbongenseni said he had abandoned the river bank in 2011 for a single-roomed RDP home in Section 7 of the township, though he still comes down daily to tend the gardens.

"It's not the river we are fighting for, see. We do not even regard it as a river – even our gardens, see, are watered with municipal water, so filthy is this river," said Mbongenseni, drawing on a slender joint.

"We remain fighting here by the river because it is as far as we can be pushed. The river bank is our battle line, see – it is where we must fight for our culture or else scatter away, like so many have already done."

He still had the pages of his memorandum on him, and when I asked whether I could make a copy I noticed that they had acquired a series of ticks and a multitude of crosses. Mbongenseni explained that he'd submitted his memo as part of a correspondence course in law.

"As you can see, de teacher gave me a low mark," he said sheepishly, and for the first time since we'd met he cracked a smile.

The author would like to thank Paul Fairall for his invaluable assistance.