How can we educate and re-educate societies to value female leadership? Does this need to start with a change in the school curriculum?

"Apha driver, we're here," yelled my companion as we wound our way up a dusty road passing a landscape of valleys, grasslands and camel thorn forests. It had been another long day of waiting, always waiting, for that infrequent lift to the nearest town, Queenstown – a journey of nearly 160km there and back – to stock up on basic provisions.

Excusing myself, I pressed my way towards the hatch at the back of the crowded bakkie, passing through a web of walking sticks, bodies, blankets and shopping bags, and stepped into the rising heat, heading towards the village of Sabalele, where I stayed for six weeks.

It lies in the Intsika Yethu municipality in the Eastern Cape, deep in the hills away from the Kei River. With its mud huts, stone kraals, pot-holed roads and prevailing poverty, Sabalele seems like any other village in this part of the former Transkei. Yet it was here, in 1942, in a land steeped in history and tradition, that Martin Thembisile "Chris" Hani was born.

In death, as in life, Hani holds a mythic place in the consciousness of millions of South Africans. His character has become a benchmark against which to measure others and his ideals provide a gauge against which to examine the country's socioeconomic transformation. I had come to Sabalele out of curiosity to see what soil had produced this liberation legend, and how it now fared almost 20 years into democracy.

Early days

Some of the first early interaction between European colonists and the isiXhosa-speaking people occurred here during the early 1700s. Their relationship quickly soured as the colonial desire for land, commerce and labour rapidly increased, and a series of battles known as the Cape Frontier Wars ensued. Lasting 100 years – from 1779 to 1879 – these ended with the Xhosa nations defeated and absorbed into the colonial economy as a source of cheap migrant labour.

More than a century later this pattern of cheap migrant labour, which so profoundly shaped the lives of Hani and millions of others, continues. Indeed, a cursory look at the villages in the area reveals that many of the working-age population are absent. Pushed from the villages by minimal investment, poorly developed infrastructure and a dearth of economic or employment opportunities, they migrate to the cities in search of work, often in labour-intensive industries such as mining.

Bongani, a former miner, lost his job after contracting tuberculosis.

During my time in the village, media reports suggested that 145 000 mining jobs might soon be lost – a frightening figure considering that few of the ex-miners I met in the villages had ever found reliable sources of income after losing their jobs.

One miner, Bongani, said that he had been retrenched eight years ago, after working on the mines for 30 years. He ekes out an existence from the odd piece job from which he earns about R500 a month. Suffering from tuberculosis, he is too old and too sick to look for work, but too young to claim a state pension. There are many such stories.

With little local employment opportunities, Sabalele reflects the wider, uneven urban-rural development of South Africa.

Ubiquitous unemployment

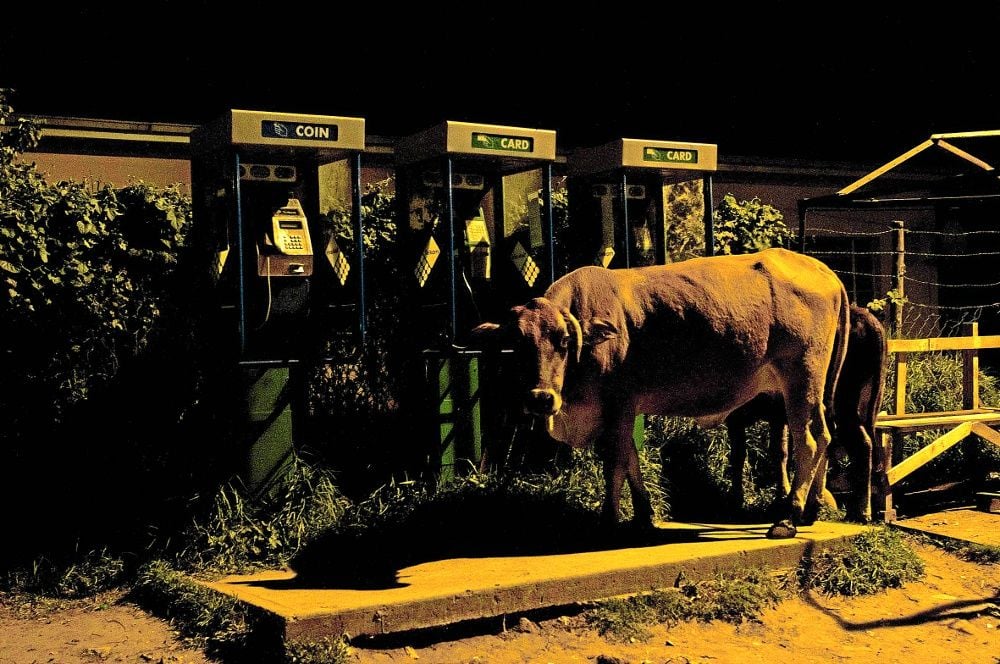

According to the Chris Hani District Municipality annual report for 2011-2012, unemployment in the district is about 57%, with many families relying on social grants or remittances as their sole source of income. Once a month, when the social grants arrive in a sort of ATM on wheels accompanied by heavily armed guards, the community becomes a hive of activity.

Arriving early at the site at the top of the hill are the hawkers, who sell their wares to the waiting queues. Women shop for staples such as mealie meal and sugar, while others come to settle debts or get paid for a service or sale owed to them from the previous month. Money brings a sense of relief to a community constantly struggling to survive.

The vulnerabilities associated with extreme poverty are widespread. Many people tell terrifying stories of growing crime visited on residents by criminals or errant youths. The blame is often laid at the door of unemployed urban young men who have returned home. Locals claim they bring with them drugs such as tik and mandrax, as well as violent crime.

Agriculture is a potential source of income for the residents of Sabalele, a rural village 79km east of Queenstown in the Eastern Cape.

But, despite a general feeling of concern, most people I spoke to did not share the same crime-related paranoia that is so prevalent in affluent South African society.

Aadan, a local Somali shopkeeper, said: "Poor people can't afford to be paranoid about crime – they live with it and deal with it as they can."

Deforestation

One evening I walked into Cofimvaba's Joe Slovo township with a local journalist, Wandile Fana. We went to the shack of a young mandrax smoker and his two friends. We started talking to an older lone figure in the corner.

Referred to as "Grootman", this was his first day out of jail in 22 years. He claims to have spent time in the same cells as Hani's killers – Clive Derby-Lewis and Janus Waluz.

What struck me most was not his admonishing the young men for their drugs but rather his lament that, because of the continued reliance on wood for heating and cooking, "there used to be a forest here before I left".

Much has changed during 20 years of democracy. Without exception, everyone I spoke to claimed that their lives had improved since the end of apartheid, with access to water, electricity and social grants being some of the most important reasons cited for this.

Nevertheless, there was a general distrust of all things political. Most people felt themselves to be political cannon fodder, their need for employment, proper infrastructure, good education and services marginalised.

Meanwhile, the Hani legend lives on in Sabalele. A number of unmarked sites such as the ruins of the hut in which he was born, general anecdotes and a good dose of popular myth-making has assured that his place as local hero is fluid enough that his legend not only stays alive, but that it also remains relevant. People speak about Hani with a sense of personal pride and loss despite the fact that many had never met him. There is a sense that, had he been alive, life would have been better.

'Dignified poverty'

Many around here want to stay in their rural homes but lack the means or necessary economic environment to do so. Often, they are pushed to urban areas that cannot absorb them. The trade-off is more employment opportunities for a rougher, less dignified existence.

This concept of "dignified poverty" was echoed in a conversation I had while walking between Qamata and St Marks village, in which a local resident observed that, although the area is desperately poor, "you will not find someone scratching for food in rubbish bins. It is not the same in the cities."

Despite having little, the community tries to ensure that no one is left to starve. People are invited to share mealie meal, a piece of bread or, when the opportunity arises, partake in a ceremonial slaughter. This is ubuntu in practice, rather than indifferent individualism. Though it may be thinly lived on a national scale, it is a very real and important social reality among many rural communities.

Despite having access to electricity, residents in Sabalele in the Eastern Cape continue to rely on wood for heating, cooking and traditional ceremonies, which has resulted in large areas of land being cleared of trees.

Vuyani, who recently returned home, said: "I couldn't find a job in Cape Town, but if I have to struggle I would rather struggle here."

Another youngster added: "I like it here, except for the poverty and unemployment. Life here could be great."

These sentiments challenge the notion that urban migration holds necessary appeal or that it marks a transition towards progress.

Agricultural potential

Meanwhile, one obvious regional asset that seems to continue to be largely underdeveloped and underutilised is agriculture.

Even with the attendant challenges of water scarcity, lack of access to markets and some of the complexities around the communal land tenure system, it has the potential to throw residents a lifeline.

Nomakwezi, a 74-year-old grandmother with a household to support, walked me through her fields on the nearby hillside. She showed me how she waters each of her stunted mealie plants with an old tin cup, refilling it every few stalks from the communal tap 200m away.

Although by no means ideal or indeed sufficient, the mealies she manages to grow help supplement her family's needs.

Progress here has been slow – too slow for many of the people I spoke to. But I was reminded that the impetus and imagination for an altered vision came from conditions vastly more dire than this.

Before he was murdered, Chris Hani foretold that South Africa's future challenge would not only be what we do in the field of socioeconomic restructuring – the creation of jobs, the building of houses and medical facilities, overhauling our education system and eliminating illiteracy – but whether we can build a society that cares.

He counselled that "we must build a different culture in this country. We must create the pathways to give hope to our youth that they can have the opportunity to escape the trap of poverty."

I learned that the work required to foster hope and realise dreams is our collective responsibility. We rise and fall together. The fate of Bryanston and Bontehewuel, Hanover Park and Hyde Park, and Sandhurst and Sabalele are intertwined.

The hardest, yet most rewarding, work is still ahead.

Nic Eppel is a photographer examining the importance of Chris Hani's legacy and ideals. His work explores questions of social and economic change as a way of understanding the current South African moment, and was initiated in collaboration with the Chris Hani Institute. Visit nicholaseppel.com.