A 'rat restaurant' test allowed David Redish to show that rats were willing to wait longer for certain treats.

Rats regret bad restaurant choices

Regret was thought to be a uniquely human emotion, but scientists have shown that this is not the case. They have now demonstrated that laboratory rats can recognise a bad decision.

“Regret is the recognition that you made a mistake, that if you had done something else, you would have been better off,” said David Redish, a professor in neuroscience at the University of Minnesota in the United States.

“The difficult part of this study was separating regret from disappointment, which is when things aren’t as good as you would have hoped. The key to distinguishing between the two was letting the rats choose what to do.”

Redish created a “rat restaurant” test that allowed him to show that rats were willing to wait longer for certain treats. Rats could choose a preferred food, but they had to wait before they got it, which often led them to choose something other than their favourite.

“It’s like waiting in line at a restaurant,” said Redish. “If the line is too long at the Chinese restaurant, you give up and go to the Indian restaurant across the street.”

When the rats got a bad deal, there was activity in their orbitofrontal cortex – the same area in the human brain that is active when someone feels regret.

“Interestingly, the [activity in] rat’s orbitofrontal cortex represented what the rat should have done, not the missed reward. This makes sense because you don’t regret the thing you didn’t get – you regret the thing you didn’t do,” said Redish.

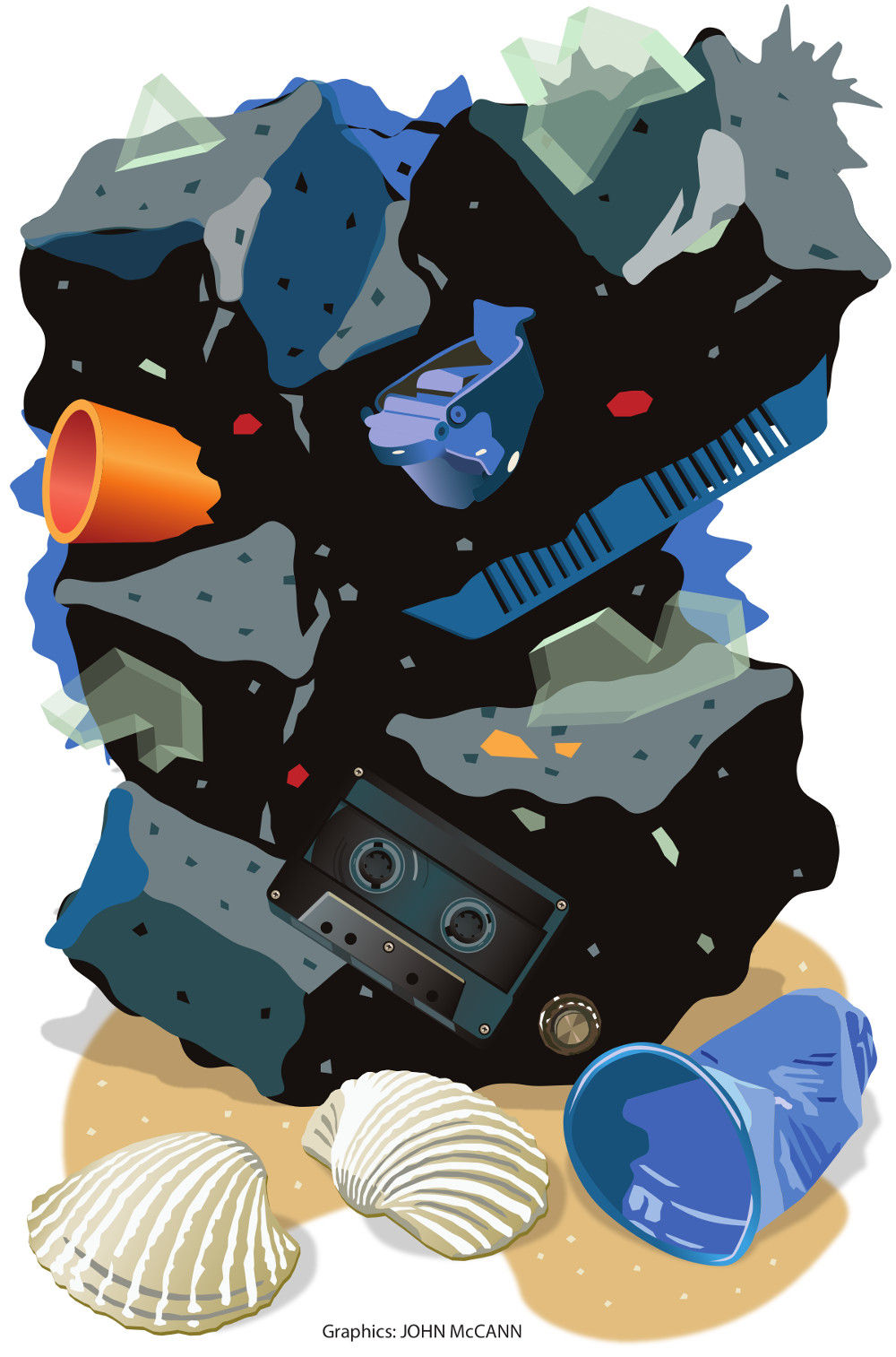

Nature turns plastic into rocks

You have to hand it to Mother Nature: she makes a plan. Plastic pollution in the oceans is a serious problem, to the extent that there are two giant debris islands in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, a large component of which is plastic.

So what does nature do? It turns the debris into rocks – “plastiglomerate” – from “the intermingling of plastic, beach sediment, basaltic lava fragments and organic debris”.

It was first recorded in Hawaii and described in a paper published in Geological Society of America Today.

It is terrifying that our plastic waste is so abundant that it has started to form the rocks under our feet.

The scientists who reported their findings in the journal, however, are very pragmatic: technically, the Earth is in the Holocene epoch of its history, but they see plastiglomerate as an important marker of the overlapping Antropocene period, which is when humans started interacting with the planet’s biophysical system.

Earth shaped the moon’s face

South Africans are often confused by the reference to the man in the moon, the “face” that Europeans and North Americans say can be seen in its craters. We are not alone. Many southern hemisphere folk can’t see it either. We allegedly have a rabbit in the moon, which we see from a different angle.

On the dark side of the moon, though, there is no face, rabbit or other image, and scientists have finally worked out why. When the Russians took the first pictures of the dark side of the moon in the 1950s their images showed that there are no lakes or marias (large, dark, basaltic plains) on the far side and that the crust is thicker too.

Astrophysicists at Penn State University in the United States think it is because of the way the Earth and the moon formed. They published their results in Astrophysical Journal Letters this week.

“The moon, being much smaller than the Earth, cooled more quickly. Because the Earth and the moon were [locked in orbit] from the beginning, the still hot Earth – more than 2 500°C – radiated towards the near side of the moon. The far side, away from the boiling Earth, slowly cooled, while the Earth-facing side was kept molten.” This meant that there was a temperature difference between the two sides and difficult-to-vaporise elements, such as aluminium and calcium, would have condensed on the far side, where the mantle is now thicker and more mineral rich. And devoid of faces and rabbits.

Forty winks knocks out kinks

As the days get shorter and the nights colder, you will be happy to know that science supports your need to stay in bed and sleep. There is a great deal of evidence supporting the idea that people who sleep more are healthier.

Sleep deficiency has been associated with obesity, heart disease and cognitive impairment, for example. But little is known about what happens in our bodies when we are sleep deprived.

Researchers from the University of Surrey in the United Kingdom exposed 26 people to a week of sleep deprivation (about five hours a night) and a week of sufficient sleep (nearly nine hours), and took blood samples to figure out what was happening on a basic physiological level.

They found that being exhausted reduces your ability to ward off illness, increases stress responses and changes the expression of about 700 genes.

Their findings were published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“This research has helped us to understand the effects of insufficient sleep on gene expression,” said Professor Derk-Jan Dijk, director of the university’s Sleep Research Centre. “Now that we have identified these effects we can … investigate the links between gene expression and overall health.”

Scope for eyeing astronomical amounts of data

Telescopes around the world – in space or on the ground – collect huge amounts of data but there aren’t enough astronomers to sift through it. Now, for the first time, South African scientists will be able to tap directly into this glut of data, a first for the southern hemisphere, according to the South African Astroinformatics Alliance (SA3).

“The VizieR Catalogue Service gives access to the most complete library of published astronomical catalogues and data tables available online, more than 12?000 catalogues to date and continuously growing,” said Sudhanshu Barway, a member of the SA3, which includes the South African Astronomical Observatory and the Centre for High Performance Computing.

The SA3 added: “With this data and checking results from previous research, astronomers can do many things … [which include] avoiding rediscovering things that have already been known or even discovering things missed by those who made the original observations.”