This year's commemorations were held under the theme "Think. Eat. Save".

Six rand – R3 for four potatoes and R3 for a cup of rice. That is Elzetta’s daily food budget.

The 23-year-old, living in Bloemendal in the Eastern Cape, has to support her twin sister and their two children. The sisters take turns doing odd jobs, so one of them can stay at home to look after their children.

The twins’ mother is dead and their father is very sick. When they cannot afford the R6 they turn to the staple diet of many poor people in the area – the ” poppie water diet”, which consists of slices of white bread and a carton of cheap and sugary juice.

Their children wake up at night because of hunger pangs and the twins have thought of having them adopted to give them a better life, Elzetta said.

“R100 usually stretches for two weeks because we don’t know where the next R100 will come from.”

Elzetta’s story is contained in a comprehensive Oxfam report that examines food insecurity in South Africa. The report, titled Hidden Hunger in South Africa: The Faces of Hunger and Malnutrition in a Food-Secure Nation, draws from official statistics and explores them in communities around the country. The report will officially be released on October 13.

Deprived of dignity

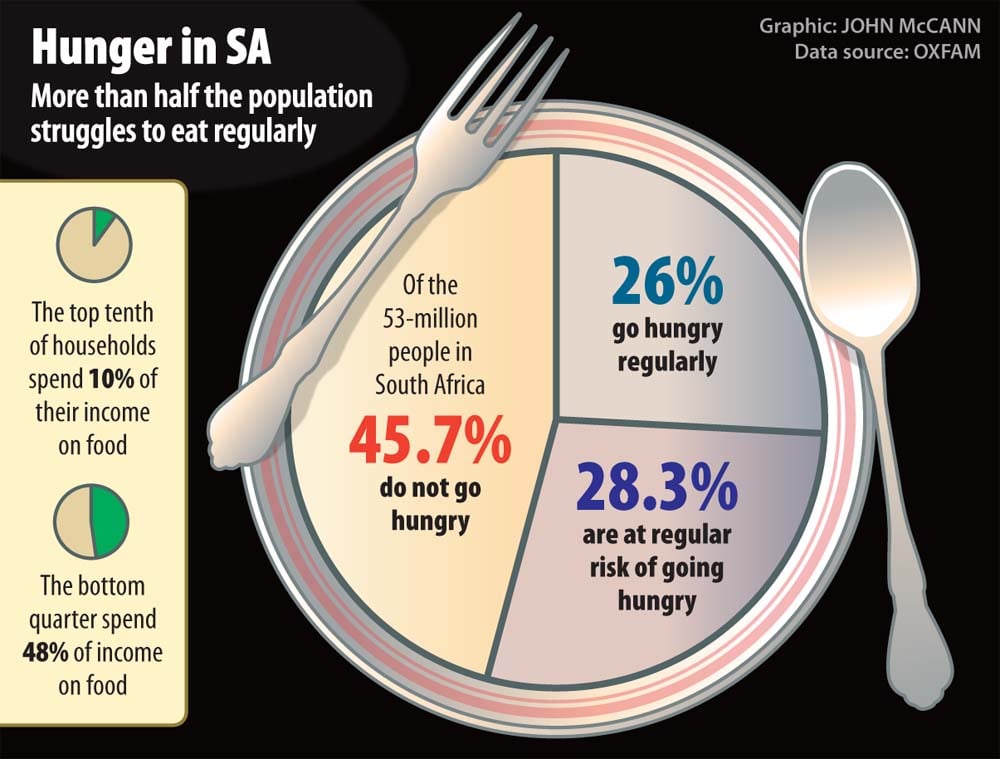

South Africa is officially food secure, according to the agriculture department. This means it produces enough food to feed its 53-million citizens. But Oxfam uses statistics from the general household survey in 2012, which found that 14-million people “regularly experience hunger”.

This means that from day to day they do not know where their next meal will come from. A further 15-million are on the verge of hunger, so any reduction to their already meagre income will push them into chronic hunger. Hunger also cripples people in other ways. Oxfam collected anecdotes from people who said hunger deprived them of dignity and demeaned them in their communities.

Inequality perpetuated

Hunger also created a malaise in people and whole communities, which it said “crushes the potential of people to get out of poverty and to prosper”. This helped to perpetuate the inequalities in society that had created the hunger in the first place.

The worst-affected communities were informal ones, where 38% faced hunger on a daily basis.

Even in formal urban areas, where the levels of hunger are at their lowest nationally, a fifth of people face hunger daily. The household survey found that 36% of people in the Eastern Cape and 31% in Limpopo suffered from food insecurity.

The number of commercial farmers has declined by 20 000 over the past decade and the area under cultivation for staples such as maize and wheat has shrunk significantly. (Madelene Cronjé, M&G)

What the Oxfam report makes clear is that this hunger is not a product of a failure in food production but in the pricing of quality food and in people’s ability to afford it.

“It is a failure of livelihoods to provide adequate cash to purchase food at the household level.”

Most communities did not have land for subsistence farming, so hunger is linked to poverty, Oxfam said.

The most food-insecure households were those headed by women or children. This was because 46% of South African men received salaries, whereas only 32% of women did.

Although the official unemployment rate is 25%, the researchers found communities where it was as high as 80%. Women were paid less, and had to spend more hours than men doing household chores.

Oxfam found this often meant households only had food security in the first week or two of the month. For the 15-million people on social grants, there was never security, it said.

Eating less

To cope with the increasing cost of food, Oxfam found that a fifth of South Africans cut the size of their meals for at least five days of the month and 17% skip whole meals to make their food stretch. People also ate less, bought food that was out of date, asked neighbours and relatives for food, bartered labour for food and borrowed from loan sharks.

As one of the world’s most unequal societies, South Africa has people living at the other extreme. The national income dynamics survey carried out by the Southern African Labour and Development Research Unit at the University of Cape Town’s School of Economics found that the median income for a South African household is R3 100 a month.

World Bank statistics show that the top 10% of the country’s households spend 10% of their income on food – an average of R29 000 a year.

The bottom 25% of households spend 48% of their income on food – R8 700 a year. Another 19% of their earnings goes towards housing, electricity and transport.

Travelling to buy food

In rural areas, many people spend hundreds of rands to travel to towns to buy food. Oxfam found that the people of Fetakgomo in southern Limpopo, for example, spend R200 to travel an hour to their nearest market and back.

The poorest 25% of the population was also the most susceptible to price shocks – such as the 50% hike in maize prices in 2012 after droughts in the United States and Russia, and the 200% increase in the price of electricity over the past four years. The poorest used mainly electricity or firewood to cook and faced expensive cooking and heating costs.

Other institutions have done similar research. The World Bank’s Nutrition at a Glance summary for South Africa this year said a third of child deaths in the country are because they lacked proper nutrition. A quarter of children under the age of five were stunted and 15% of babies were born underweight.

With half of the population over the age of 15 obese, the summary said people were not getting healthy food with high nutrition levels.

No guarantee of food security

There is no single Act that deals with food security. Section 27 of the Constitution says: “Everyone has the right to access to sufficient food and water.”

The onus is on the state to progressively guarantee this right, through “reasonable legislative and other measures,” the Constitution says.

But, as with other rights, these have to be guaranteed through other legislative measures.

Professor Sheryl Hendriks of the University of Pretoria said the last attempt to have a dedicated food security Act did not receive Cabinet approval when it was proposed in 1997. This meant there was little impetus to protect farming and guarantee the country’s food security.

South African farmers received less financial and administrative help than in any other industrialised nation, she said.

Commercial food production was in decline because farmers faced uncertainties about land tenure, wage demands and an absence of supportive legislation and agricultural policies.

The number of commercial farmers had dropped by at least 20 000 in the past decade, Hendriks said. They produced 4.4 tonnes of maize (the staple crop) a hectare, whereas smallholder farmers produced 1.1 tonnes a hectare.

“The area under cultivation for maize and wheat – the main cereals of South African households – has declined significantly over the last decade. This puts national food security at risk,” Hendriks said.

Poor nutrition means obesity

The Oxfam research said that South Africans are becoming more and more obese because of the poor quality of the food they ate.

Data published in the Lancet this year found that 68% of South African women and 35% of men over the age of 20 were overweight.

This was because their meals did not have vegetables and proteins, and contained such poor nutrition that large quantities had to be consumed for people to feel full.

Addressing food security was at the core of solving a host of societal problems, Oxfam concluded.

“Food insecurity and hunger destroy human potential, strip away human dignity and foster inequality throughout society,” Oxfam said.

“This should be a national scandal.”