There is a passage in Phaswane Mpshe’s 2001 novel Welcome to Our Hillbrow that speaks to the mystery that finally compelled Thabiso Sekgala, arguably the brightest hope among a new generation of South African photographers, to take his own life.

“There were no outlets for your bottled-up feelings … With so much on your mind, suicide and relief could only be synonymous attractions.”

The finality of Sekgala’s action — he hanged himself in his Johannesburg flat last week — has deeply shocked those who knew this gentle and upbeat photographer.

“I think a lot about his last hour,” said fellow photographer Sabelo Mlangeni, a close friend who made the grim discovery. “I am trying to make sense of the whole situation.”

Born in 1981, Sekgala was a year younger than Mlangeni. They met in 2008 in Mlangeni’s studio on Gandhi Square in central Johannesburg. Sekgala, then still studying at the Market Photo Workshop, a school of photography in Newtown, introduced himself and they developed a close friendship.

“We shared a lot of frustrations,” Mlangeni said. Some were personal and related to Sekgala’s family background. Although born in Johannesburg, he was raised by his grandmother in a settlement near Hammanskraal, north of Pretoria.

Her death a few months ago weighed heavily on Sekgala.

The pair spoke mostly about work, and in particular about the difficulties associated with being a photographer in South Africa. These included the “broken feelings”, as Mlangeni put it, of working in a field where security was always an issue.

But there were also situational issues: the ethics of portraiture, the subtle vagaries of a white-dominated art market and, perhaps the most pressing, the economic difficulties of forging a career as a photographer in a country where this vivid and democratic medium is not widely collected.

Sekgala initially worked as a waiter at a fast-food outlet in Pretoria and later in Johannesburg.

It was a chance encounter with a photographer in Johannesburg that led Sekgala to photography and to the Market Photo Workshop in 2007.

In 2010, he became the third recipient of a Tierney Fellowship, a prestigious early career award that gives recipients a cash grant and the opportunity of one-on-one professional mentorship. Sekgala worked with Mikhael Subotzky, who was the same age as him.

“We were friends who came from different worlds, yet we had so much in common,” Subotzky said.

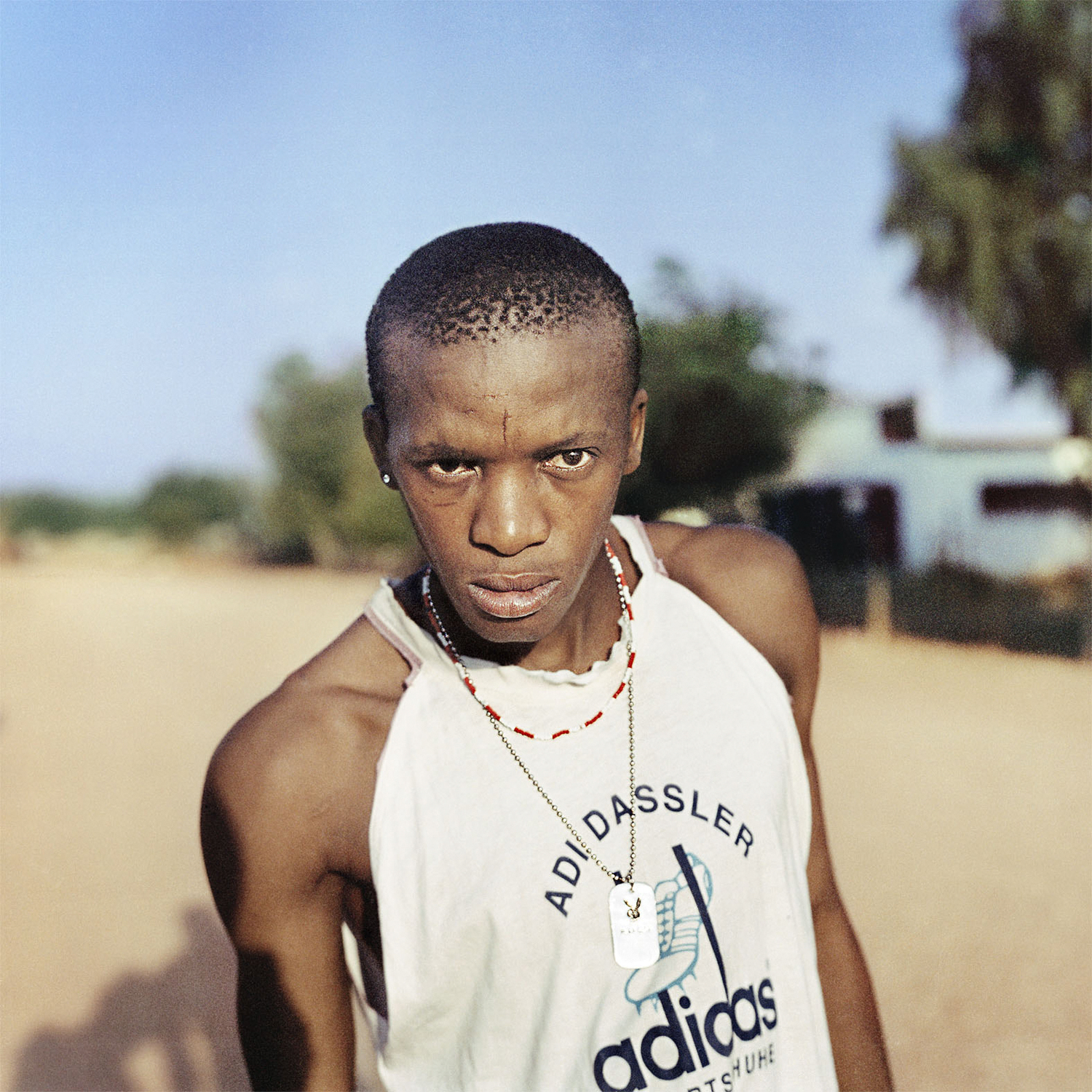

He helped Sekgala to select the images for his debut solo exhibition. Shown at the Market Photo Workshop in 2011, Homeland consisted of colour portraits of young men and women living in the former Bantustans of KwaNdebele and Bophuthatswana. Brooding descriptions of the semi-rural landscapes accompanied the photographs.

Tender, curious and strangely hopeful, this formal, accomplished body of work catapulted Sekgala on to the global stage. In 2011, he was nominated for the Paul Huf Award, previously won by Pieter Hugo and Subotzky.

Homeland was included in the elegiac survey exhibition of Nigerian curator Okwui Enwezor, Rise & Fall of Apartheid. It was seen in New York, Paris and Munich, before coming to Johannesburg this year.

“A lot of his portraits have this unbelievable tension,” Subotzky said. “His sitters are conscious of being observed and, at the same time, they are comfortable with that. That tension makes it very powerful.”

Akinbode Akinbiyi, a Nigerian-born photographer who lives in Berlin, said of Sekgala: “Thabiso was really talented and was prepared to do the nitty-gritty hard work. Already, he had gained his personal eye, using the square format and colour film to express his acute sensitivity.”

Akinbiyi sometimes met Sekgala during his residency at the Kunsterhaus Bethanien in Berlin.

Sekgala capped his stay there with an exhibition of portraits and urban landscapes taken in Berlin and Istanbul. Exploring issues of home, migrant identity and displacement alongside the gentler pleasures of urban living, Paradise, as Sekgala titled his exhibition, included portraits of white Berlin women posed in Turkish male-only teahouses.

His work was hailed by curator Simon Njami for its “compassion and empathy”. Yet, in an interview earlier this year, Sekgala spoke about the indifference that met his photographs in Berlin. “People want to see a certain picture of Africa,” he said, adding that he preferred to create subtle work. “I think there’s a lot of better stuff to photograph than this negative stuff — better than poverty and violence.”

His photos of the impoverished living conditions and landscapes around Marikana bore out his driving impulse: to quiet and still reality instead of creating a spectacle of it. It was a risky stratagem, at least commercially. His polished debut solo exhibition at Goodman Gallery earlier this year generated only a few sales.

Remembered by Kenyan photographer and friend Mimi Cherono Ng’ok for his “searching” qualities, Sekgala purposefully allied himself to a “new generation of artists” with a “positive approach”. To this end, he was involved in discussions to form an association of black photographers with Mlangeni, Andrew Tshabangu and others. It was Sekgala who gave the informal group its name: Umhlabati, which means earth in isiZulu.

Tshabangu spoke of his deep shock over Sekgala’s suicide, which adds the young photographer’s name to a list of bright stars eclipsed too soon by their own hand. They include Nat Nakasa, Kabelo “Sello” Duiker and Moses Taiwa Molelekwa, who also hanged himself.

Although his dark moods are known, the reasons for Sekgala’s suicide are not. “I am seeing his decision as a very brave one,” Mlangeni said. “We all sometimes find ourselves in situations where we have these thoughts but you stop yourself.”

Sekgala didn’t.

Thabiso Sekgala, born 1981, died October 16 2014. Unmarried, he is survived by a son and daughter.