Thrown a line: Skipper Gregg Louw hopes the permit will give his Hout Bay business

The Complete South African Fish & Seafood Cookbook, published by CNA in 1981, has an entry headed “monosodium glutamate [MSG]”. Author Alicia Wilkinson says, although there is controversy over its use, “I always use it when cooking fish. “Frozen fish, and hake in particular, gain much from a sprinkling of MSG. I often use it in place of salt. It is sold in this country under the trade names Fondor, Aromat and Zeal.”

Back in 1981, Wilkinson did voice her concern about the sustainability of fish in South Africa, but offered little in the way of advice to consumers about which fish were endangered, or what to do about it. To be fair, sustainability was hardly a catchphrase, and the world’s resources seemed limitless. (This being the Eighties, she did offer a recipe for toast with anchovette fish paste, chutney and cheddar.)

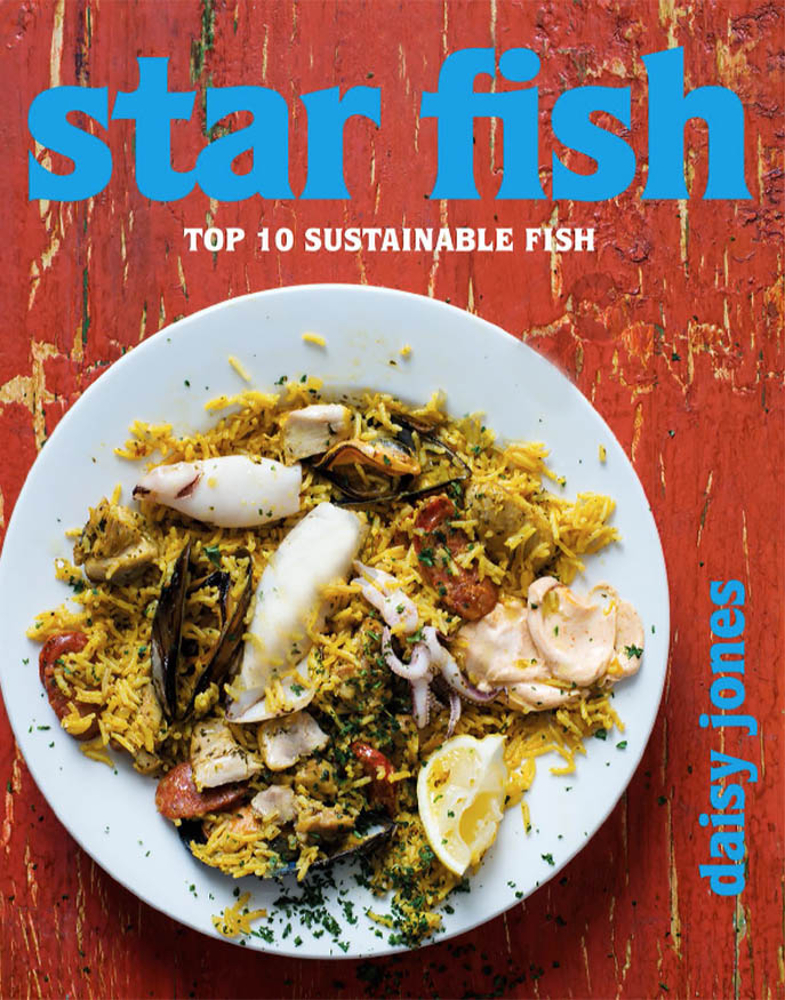

The ebullient Daisy Jones, author of Star Fish (Quivertree), a new book on cooking with sustainable fish, believes that consumers, by refusing to buy certain fish, have brought some change to the industry. “In the 1980s there was a video of a tuna being caught, along with dolphins, and being killed. Consumers refused to eat tuna that was caught in that manner and eventually government responded by banning that kind of tuna fishing. It starts with us; the message goes to the profiteers.”

Jones said she had been shocked to find out that some of her favourite fish – Cape salmon, kingklip, sole – were on the Southern African Sustainable Seafood Initiative (Sassi) orange list, and said the journalist in her thought: “Here’s a story”. Sassi was started in 2004 by World Wide Fund for Nature and aims to “empower consumers with the know-ledge so that they can make a more sustainable seafood choice”, says Janine Basson, WWF-Sassi manager.

It is by now well known that Sassi has three lists: red, under which fall species that can no longer be sustainably caught, and are illegal to sell and buy in South Africa; orange, which includes species about which there is cause for concern, either because they have been overfished or are vulnerable; and the green, which contains the best managed fish stocks and species that can handle current fishing pressure.

‘A cookbook underpinned by an environmental imperative’

The red roman, for example, is on the orange list. This fish has delayed sexual maturity and, despite being found from Coffee Bay to Cape Point, has only now started to recover after marine protection areas were established at Tsitsikamma and Gou-kamma on the Garden Route. Jones chose 10 sustainable fish from the green list. Four are locally farmed: oysters, rainbow trout, mussels and dusky kabeljou. The other six are anchovies, squid, snoek, hake, yellowtail and sardines (or other oily fish). She then started her research, in the kitchen and among those people in the sustainable fishing industry.

The book took two and half years to write, and her family and friends were treated to an extensive array of sustainable seafood dishes. It’s a unique cookbook underpinned by an environmental imperative or, as she puts it: “If the WWF and Sassi say a fish is in trouble, why be a schmuck?” It is not just a collection of tasty recipes someone knocked up in their kitchen. It was also this month named as best cookbook of the year at the Sunday Times Cookbook Awards.

Sassi goes through an exhaustive assessment process in determining the sustainability of a species. It starts with an initial assessment by WWF, which is then reviewed by scientists. These are then published for public comment, after which there’s another review process and then, finally, a team of experts produces the final assessment for the particular species. The assessments also take into account the way in which each fish species is caught.

Bruce Mann, a senior scientist at the Oceanographic Research Institute in Durban, told me this week that, once you dig into the science behind the Sassi lists, it gets quite complicated. Mann’s area of expertise is line fish. Asked which species he was particularly concerned about, he mentioned slow-growing reef fish species such as red steenbras, black musselcracker, dageraad (one of the sea bream), and another fish called seventy-four seabream.

The green, orange and red list

The highly nomadic and fast-growing dorado is on the green list when caught by the commercial line fishery, but moves to orange when it’s caught on a pelagic long line (which can be very long – kilometres – with a series of baited hooks). The difficulty for the consumer, says Mann, is that a waiter or fishmonger is seldom going to know how the fish was caught. So although there is often little argument about species on the red or green lists, those on the orange list are, to some extent, open to interpretation and consumers are asked to consider the implications of their choices.

“The orange ones are hard. You can have some species that are theoretically ‘light’ orange regarding their status and/or the fishery that harvests them and others that are ‘dark’ orange, and a whole range in between,” he says. What about fish that move between lists? Mann said the santer (soldier) used to be on the green list, but after the recent assessments the seabream moved to the orange list owing to uncertainty about its stock status.

For Jones, “it feels a lot simpler to me to memorise the list of 10 fish. For me it’s 10 yesses, and everything else is a no.” She says confining herself to cooking with sustainable fish made her feel like a pioneer, and a bit like a bearded hipster, you know, like the “kind of guys who get mucky and make craft beer or artisanal cheese and then sell it at an impossibly hip Sunday morning market”.

Interspersed between the recipes are stories about those in the sustainable fishing industry, such as when a fishmonger tells her the trekkers have taken two tonnes of yellowtail from Fish Hoek beach that morning. “Ask for Giem,” she’s told. She watches the catch from the windy beach; Giem wading into the water, urging his men on: “Tre-ek Tre-eKK!” as they pull on the rope. The net is dragged on to the beach. “The slapping of hundreds of live fish on the wet sand makes a sound like hard rain on a tin roof. People stand entranced, watching the fish die.”

She also visits Schalk Visser, the most successful mussel farmer in South Africa, at his mussel farm on Pepper Bay in Saldanha. He grows his mussels on green nylon ropes, which become so densely packed “that you wouldn’t be able to get your arms round it”.

‘The recipes are not brand-new’

The global market for seafood is complex. It often passes through a number of countries and changes hands between traders and distributors. Most of South Africa’s catch of calamari is exported and most hake is imported from Namibia. Most prawns come from India. It also turns out South Africans eat a lot of pilchards, which, with hake, make up 70% of the seafood consumption in the country.

It is hard to be precise, but it is thought that South Africans eat just over 6kg fish a person in a year. This doesn’t seem very much, especially as it appears South Africans eat more than 15kg meat a person. Anecdotally, many people – certainly in Johannesburg – still seem mistrustful of fish, or at least the kind that you buy from the fishmonger, lying on ice, dead eyes staring dully back at you.

I bought a piece of “fresh” hake the other day from a reputable northern suburbs fishmonger, and it had begun to smell before I got to the car. Jones’s “star fish” are not “beautiful, lean, white fish”, and are, as she says, rougher and tougher, so “you don’t have to be good at sauce”. She learned new techniques, such as (a little bacalhau) salting hake the night before, which firms up the flesh. There’s a good recipe for a stew of salt hake, tomato, chickpea and parsley, spiked with chilli and thickened with potato.

Many of the recipes are not brand-new, and some have been adapted and tweaked from cooks such as Nigella Lawson and Jamie Oliver. As Jones says, it’s not as if she could “reinvent fish in a beer batter”. I did, however, find it helpful to have all these fish recipes in one book. If you’ve just bought one of the sustainable fish, you’ll find something exciting to do with it, such as snoek samoosas with dhania sauce; sesame seed yellowtail; or even a fake tuna melt jaffle.

Family-style recipes

Jones did invent the tuna rice salad “when she was about 10”. It even has pink sauce, made with mayo and tomato sauce. Other recipes she is proud of are the poached haddock on bubble and squeak and her adaptation of salad niçoise: two types of fish – anchovy, canned tuna, black olives, potato, onion and strong green herbs. She also “had a good go” at the smoked snoek pâté.

These are family-style recipes and, as she says, are not for a dinner party: they are “Dinner. Or lunch”. I tried the “very versatile yellowtail vindaloo” that worked very nicely, the piquant sauce staining the chunks of yellowtail. A colleague also spoke highly of the creamy fish pie, with, among other things, frozen haddock, double cream and mature cheddar. By way of a disclaimer, Jones and I are friends, having met as reporters for another newspaper a long time ago, and in the book she mentions an anchovy pasta I made while on a hike.

On a hike, and in the book, there are always plenty of opportunities to crack jokes. As she scoffs: “A long list of ingredients? You call that a lot of prep. I call it a chance to spend time with my man Billy Joel.”

Where to buy, how to cook

Fish Shops

Cape Town

The Little Fisherman: Weeks after visiting my friend in Cape Town, he torments me with SMSes from the Little Fisherman advertising their specials. There are two branches, one in Lakeside and the other in Newlands. I have bought huge chunks of tuna, yellowtail and salmon from the Lakeside branch. I have never seen better fish. Newlands (021?794?5526), Lakeside (021?788?3583)

Fish 4 Africa: A small, and when I visited, smelly shop in Woodstock that was well stocked with hake, tuna and yellowtail. They also have frozen calamari and mussels. (021?448?5258)

Johannesburg

Mediterranean Fish Centre: The shop is about halfway down Jules Street in Malvern. It’s a giant place, with a long counter. On the left they serve fish, on the other side, meat. They also have dried bacalhau, which stinks the place up. Breathe through your mouth. (011?615?5760)

Fisherman’s Deli: The fish fly out of this little shop in Dunkeld West. There’s usually a long queue, especially on Saturday mornings. There is often a hunk of fresh tuna, and the shop always seems to have fresh Scottish salmon, both of which will require second mortgages. There is also a selection of frozen prawns and crayfish. (011?325?2577)

Fish Books

Free From the Sea: The South African Seafood Cookbook by Lannice Snyman and Anne Klarie (Lannice Snyman Publishers)

The classic South African seafood cookbook is now sold out and not under reprint, but there are some used ones available on Amazon and elsewhere. It was first published in 1979 and has been through 14 impressions. It has sold over 150?000 copies, which probably makes it South Africa’s bestselling cookbook of all time.

The Livebait Cookbook by Theodore Kyriakou and Charles Campion (Hodder & Stoughton)

The Livebait fish restaurant in London was started by Greek chef Theodore Kyriakou, and this is the cookbook, written with food writer Charles Campion. It’s a mix of the down home and the complicated: there will be a recipe for gigandes plaki (a comforting stew of large white beans cooked in stock with bay and tomato) next to one for a John Dory, spinach and potato pie with a Pernod sauce. I will always be grateful to Kyriakou for teaching me how to make avgolemono sauce, based on the famous Greek soup made with eggs and lemons, which he pairs with halibut (I used kingklip) wrapped in poached lettuce leaves.

Fish by Sophie Grigson and William Black (Headline)

This is almost an encyclopaedia, with chapters on preparing, buying, storing, cooking and classifying fish. The couple have collected a vast number of recipes, and it was here that I first learnt to make hake roasted with anchovies, rosemary, garlic and breadcrumbs. They helpfully include an international fish chart, which has a column reserved for Afrikaans fish names.