Chicagoans are resilient. I’ve lived here my entire life and know this to be true more than most anything else about the city. From an environmental standpoint, the brutal force of our winters is a metaphorical test. If you can survive here, you can survive anywhere. Yes, it is about the cold and the snow and the grey. But it is also about the things that never seem to go right here: “machine” politics, bureaucratic fraud, a broken system of public services.

But Chicagoans also like to keep these things secret. That leads to public embarrassments and indictments on why we are considered the “second city”. Our rampant, summertime violence is yet another example.

That is why, when Amazon announced a new film project created by Spike Lee and entitled Chiraq, I immediately felt nervous. Would this be yet another cold, voyeuristic look at the city from an outsider? Would I (and many other Chicagoans I know) be left feeling both contempt for the film’s “not getting it right” mixed with anger over its saying what we like to avoid saying?

Chiraq – a portmanteau of Chicago and Iraq – gained traction in the national media as Chicago’s murder rate surpassed that of larger American cities such as Los Angeles and New York, as well as casualties of the Iraq war itself (between 2003 and 2011, Chicago saw more murders than American deaths during Operation Iraqi Freedom). As Chicago’s violence became a talking point within the mainstream media, creative interpretations of that violence from locals and outsiders alike also emerged.

Recent albums from Chicago rappers Lupe Fiasco and Common were the latest representation of Chicago’s ongoing violence. Fiasco’s Tetsuo & Youth focused on his upbringing on the West Side of the city, while Common’s Nobody’s Smiling explicitly focused on the city’s violence.

The best among the most recent cinematic releases was The Interrupters, a documentary from Steve James and Alex Kotlowitz about CeaseFire, an activist group in Chicago that intervenes in street fights and shifts confrontations to demonstrate more effective methods of conflict resolution.

Its critical success and strength came as no surprise to Chicagoans. James also created Hoop Dreams, a documentary about two black high school pupils with dreams of becoming professional basketball players.

Kotlowitz, a journalist, wrote There Are No Children Here, a book about two brothers growing up in the city’s Henry Horner Homes, a series of projects in the near west side of the city. It was required reading for many local students, especially those in the nearby suburbs. Both James and Kotlowitz are Chicagoans and, although they are both literal outsiders to the environments they covered, their position as Chicagoans gave them an advantage above other creators. There is a truth in living here that no outsider, not even Spike Lee, could capture to its fullest.

Last year, Noisey produced a series of films about the subject with the same name as Lee’s forthcoming film. Chicago’s drill music scene gained prominence, thanks in part to the success of Chief Keef (Keith Cozart). His temporary reign as the “next great Chicago rap hope” was quickly stymied because of the realities of his life within the city. A host of legal troubles and gang-based problems followed Cozart’s rapid rise, including an investigation into the murder of rival rapper Lil Jojo after Cozart mocked his death on social media.

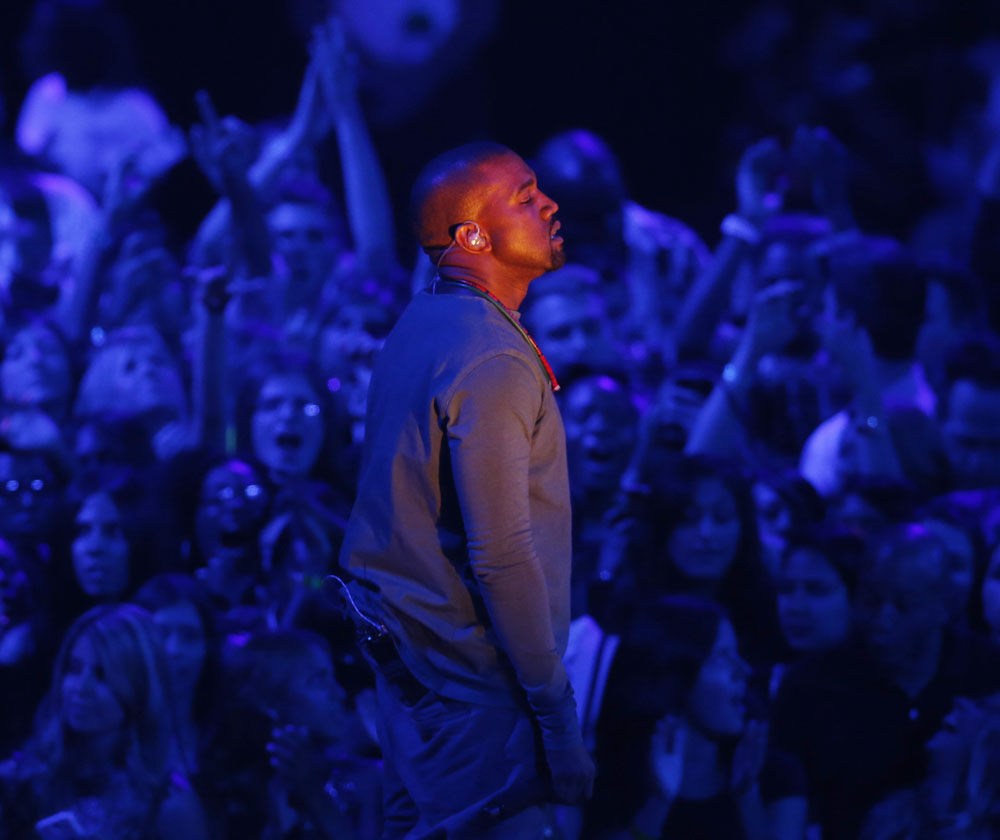

For his film, Lee is reportedly looking at Samuel L Jackson, Jeremy Piven, Kanye West and Common for roles. The possible inclusion of the latter two is encouraging. Common and Kanye West are Chicagoans and – despite their current distance from the city – have better insight than others into what the city is like or has been like. West, however, is less tied to the city than Common, if his current interests are an indication. Piven is also from the Chicago area suburbs.

These depictions of Chicago don’t explicitly outline Chicago as a gun-toting, crime-ridden failure, but they are the most visible. For outsiders examining the city, it paints a less than accurate picture of the city and plays into the narrative that Chicago is a one-issue city. The public uses these art forms as the only representation of Chicago, even though statistics show that Chicago’s violence has improved in recent years .

The truth is that Chicago is far more complicated than the dominant media narrative suggests. To understand the violence in Chicago is to understand the city itself, a place that is more fractured than united. This is a city comprising neighbourhoods and micro-neighbourhoods.

And although they make the city interesting, compelling and unique, neighbourhoods also work to divide the people within it. It is easy for one to live here his or her entire life and never experience any other part of the city than the one they’ve always known and called their own. Besides being geographically vast and sometimes incomprehensible (beaches and prairie share the city with rivers and vast swaths of concrete), it is also a city created with hard lines to divide race and class.

All of this matters because it adds to Chicago’s story of how violence perpetuates on city streets. A large portion of the city’s most “headline-worthy” violence is found in a handful of neighbourhoods.

The United States website NeighborhoodScout created a list of the 25 most dangerous areas in the US; six of the 25 spots were in Chicago. The West Lawndale neighbourhood ranked 24th on the list, with 71.55 violent crimes per 1?000 residents, and the Washington Park neighbourhood ranked 20th with a rate of 75.18.

These stories and this focus might be embarrassing and hard to watch, but the stories are accurate and need to be told. Chicago is a city that encompasses many things – ugly and beautiful, weird and frustrating, stultifying and invigorating – all at once.

These stories might be upsetting, but they are also real. They force the world at large to look at the ways in which violence develops in microcosms and subsequently in our own back yards. But they also provide Chicagoans with the opportunity to look inward, to not ignore violence and pretend that it is only a problem for one part of the city.

In some instances, these voyeuristic interpretations may come across as lazy (like CNN’s glib Chicagoland) or sensationalist (like the rush of national media attention after a bloody, early summer weekend).

But I trust Spike Lee, a director who understands and has highlighted complex, multifaceted representations of black lives in smart, progressive and important ways.

When The Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts and 4 Little Girls are perhaps his strongest nonfiction works. And despite the film’s initial criticism, Bamboozled has stood the test of time because it predicted an all-too-familiar representation of white reactions to black entertainers (consider Dave Chappelle’s exit from Chappelle’s Show).

Lee may be an outsider, but he is an outsider who understands the complexities of his subjects and will, hopefully, help provide a more complete picture of Chicago. – © Guardian News & Media Ltd, 2015