Louis Liebenberg

In September 2014 Antonino Messicati Vitale, a Sicilian Mafia boss whose name is whispered with respect and more than a little fear in parts of Palermo, hatched a plan to flee Italy using a high-tech silicon mask to conceal his identity. But investigators were watching closely and on October 8 2014 they raided his home and arrested him. He is now awaiting trial.

“We aren’t certain about which country Antonino was going to fly to,” the head of the investigative section of the Carabinieri police in Palermo told reporters. “But it is very likely he was going to South Africa again.”

Messicati Vitale had visited family – in both the Mafia usage of the word and the more traditional blood-relations type – in South Africa before. He had also already helped to extend the family business – again, in both senses of that word – in this country.

This week a new investigation spanning Italy, Namibia, South Africa, Zimbabwe and countries far beyond can reveal parts of that Mafia business, and how Italian organised crime continues to build its footprint in Southern Africa, using South Africa as its base.

For the Mafia, South Africa has long proved to be a place where sanctuary can be found, where friends and family can easily shield a man from unwanted attention and provide a comfortable life. In the past 30 years, it has also become one of the most important foreign economies for the Cosa Nostra. The organisation deftly managed this country’s transition to democracy and, like other, more legitimate businesses, used it as a base from which to expand northwards.

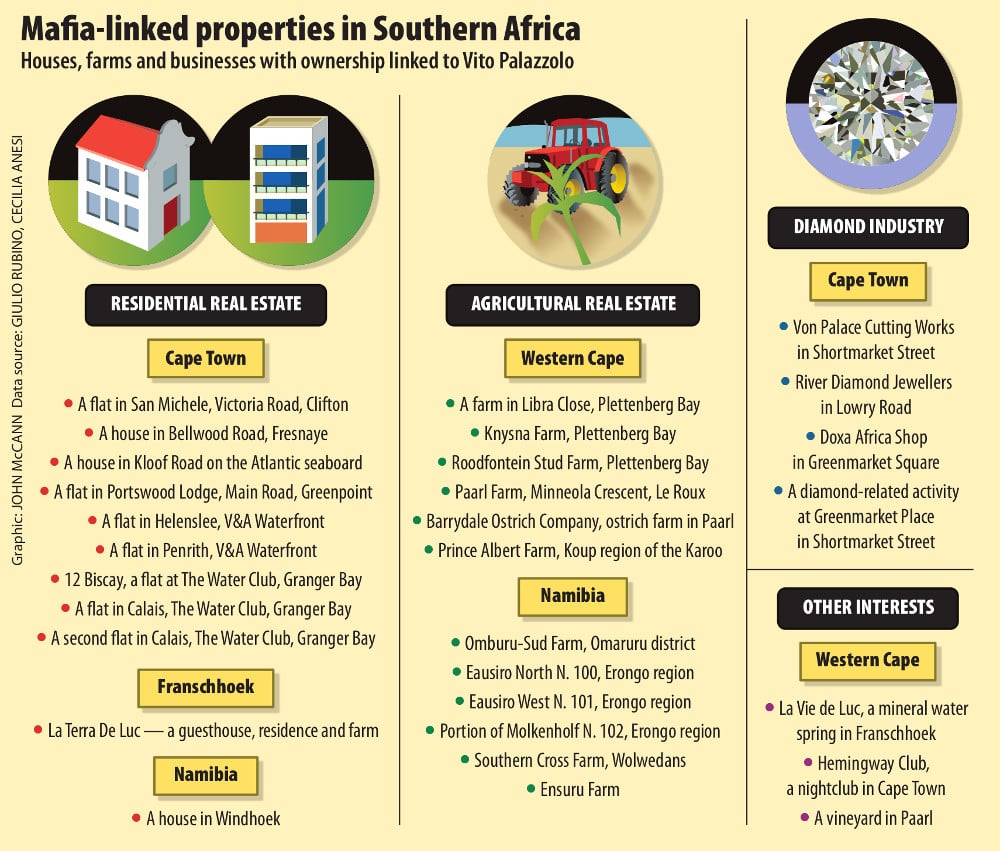

Today Mafia money reaches from rich diamond concessions on South Africa’s West Coast to the bloody Marange diamond fields in Zimbabwe; from a bottled water plant in Franschhoek to an ostrich farm in Namibia. Much of that is the legacy of one man: Vito Roberto Palazzolo, aka Robert von Palace Kolbatschenko, for years the most valued banker of the Cosa Nostra and a resident of South Africa, with connections reaching deep into local business and politics.

The Wealth4u Mining and Exploration business was opened to work a West Coast diamond concession.

Now the reach and depth of those connections and business interests may finally start to emerge.

At the end of 2014, after a year-and-a-half in Milan’s Opera Prison, living under harsh conditions reserved for organised crime figures, Palazzolo decided to talk to Italian prosecutors.

To date, the content of what he has had to say over the past four months remains secret, and the extent to which he may be co-operating with authorities is not yet clear.

It is possible that his conversations could come to nothing; he steadfastly denied, dismissed and laughed off allegations against him for decades, even when a Palermo judge convicted him in absentia in 2006, and even after he was arrested on an Interpol warrant in 2012, while travelling from Thailand to South Africa.

Anything he does have to say will be of enormous interest to authorities not only in Italy but also in South Africa, where new investigations have found ample evidence of dirty money, sexual entrapment and blood diamonds, all woven together through family ties that reach back to the highest Mafia thrones of Sicily.

Blood ties

Such ties, of loyalty if not blood, link Palazzolo – well-known in South Africa thanks to a series of run-ins with the law going back to the mid-1980s – to Messicati Vitale, who is as obscure in South Africa as he is notorious in his home country.

Both belong to the Corleonesi Mafia clan, today headed by one of the most wanted fugitives of the world, Matteo Messina Denaro, whose surname means “money” and who made the Cosa Nostra a successful capitalist venture. In a sense, Palazzolo and Messicati Vitale are the sons of the same godfather, as well as two of the Mafia’s biggest African investors.

Although Messicati Vitale’s fake-face attempt to flee Italy last year failed, Palazzolo succeeded in a not entirely dissimilar caper 28 years earlier. Sentenced in 1985 to three years in a Swiss prison for laundering heroin money, Palazzolo combined a 36-hour Christmas pass with a fake passport to escape to South Africa.

Antonino Messicati Vitale (second from right), who is awaiting trial, is seen with, among others, his uncle Salvatore Ferrante (right) and Louis Liebenberg (centre).

The same financial gymnastics that landed him in a Swiss prison had previously put Palazzolo in touch with South Africans looking to sidestep international sanctions on the apartheid regime through the use of underworld money channels. By the time of his escape, he already owned a Cape winelands farm. Though he arrived a fugitive, and supposedly broke, he almost immediately began buying assets and property – and legal status, first as a citizen of the Ciskei homeland and, by the end of 1995, as a South African citizen.

A short stint back in a Swiss prison, after he was traced by Swiss police and ejected from South Africa, barely slowed the pace of his acquisitions, or his wooing of, first, the National Party and subsequently those connected to the ANC during a time in which South Africa refused nine extradition requests from Italy. Nor did a Mandela-era inquiry into the extent of Mafia involvement in South Africa deter Palazzolo or, it seems, Messicati Vitale after him.

Political ties

Over the years, Palazzolo’s cultivation of the likes of then defence minister Pik Botha and MP Peet de Pontes has been revealed, and allegations raised that Palazzolo helped, or attempted to help, the then South Africa Defence Force turn diamonds into military hardware. Palazzolo’s property has been raided, stories about him published and many hours spent in courts as he fought off attempts at prosecution. There is a veritable mountain of paperwork on Palazzolo’s connections with South Africa.

The paper trail on Messicati Vitale is smaller and it begins with a single photograph.

In 2011 the Italian Carabinieri noted that Messicati Vitale, who holds the Mafia throne of the Villabate borough of Palermo, had travelled to South Africa. He had met, they learned, the Ferrante family, which had been settled in South Africa since the late 1950s, and which turned out to be related to Messicati Vitale.

Investigating the Ferrantes took Italian police as far as a company named African Dune. Looking into it, in turn, brought up a business venture named the Zimbabwe Diamond Opportunity.

And, there, in a photo of seven people involved in Opportunity, was Messicati Vitale, a man already convicted as a mafioso in 2000, and now charged with extortion, influencing public calls for tenders and armed Mafia association.

Vito Palazzolo in Thailand before his extradition to Italy, where he is serving a jail sentence. (Chaiwat Subprasom, Reuters)

In the picture, Messicati Vitale half hides behind his uncle, Salvatore Ferrante. In the centre, leading the negotiations, is a man who wears the widest smile of all: Louis Petrus Liebenberg.

Liebenberg, at the time, was regarded both as a crucial business partner to the Ferrante family and a new “family” member. He was in a romantic relationship with Salvatore’s eldest daughter, Giuseppina, called Pina by friends and family.

Born in 1964 in Port Nolloth, 85km south of the Namibian border, Liebenberg is the son of a pastor.

One day, a wealthy member his father’s congregation, Johannes Huisamen, decided he wanted to help the young pastor’s son. At the time, Huisamen owned the mining rights to some the most exclusive marine diamond concessions along the West Coast close to the Orange River mouth, including those of concession 10.

Perhaps he wished to curry favour with the Lord but, whatever the reason, Huisamen passed Liebenberg the marine mining rights to the concession. It is one of a few privately owned marine concessions, according to which mined diamonds can be sold privately and do not have to pass through the state.

In 2005 Liebenberg opened Wealth4u Mining and Exploration to work concession 10, which “has at least 600-million tonnes of diamond gravel to work”, Liebenberg told the Investigative Reporting Project Italy (IRPI), one of the groups that collaborated in this investigation. “There are up to two million carats of diamonds laying there.”

Two years after opening Wealth4u, Liebenberg’s fate became intertwined with Ferrante’s.

“It was 2007 when I met Pina at a restaurant in Johannesburg,” Liebenberg said. “I did not know that [the Ferrante’s] work method was to send out the women to meet wealthy men in South Africa. Pina and a friend of hers attended several restaurants where rich men ate.”

Pina is a typical Sicilian beauty, dark-haired with dazzling blue eyes. She is charming and fun, and men like her.

“Pina and I started seeing each other on a regular basis,” Liebenberg said of a time when he was mainly concerned with raising money to exploit the concession.

Antonino Messicati Vitale (seated) is said to have helped expand the family business in South Africa.(Sonny Tumbelaka, AFP)

Liebenberg said the two started a relationship in February 2008, at a time he was going through an expensive divorce.

“Pina said she could protect me against my wife’s claims and that I could put all my assets in her name.”

Liebenberg mulled over the proposition, and then Pina introduced him to her family, an important step for an Italian daughter, who told him how much they wanted to help.

“You know, being Afrikaans, we are not that close to family,” Liebenberg said. “I liked the fact they were very supportive of me going through my divorce. We were always having dinner and lunch together and it really felt like a family.”

Liebenberg accepted the offer, transferring all of his assets to the Ferrantes. Almost immediately, he employed three family members in key positions.

Although he kept his role as chief executive of all the diamond companies, he was now technically working for the Ferrante family.

And the deal was not limited to the companies: “They convinced me

I must take all my animals, my cattle, boats, equipment, all of it, and put in Pina’s name,” he said, “and I did that.”

With the assets now Pina’s name, and Liebenberg’s wife heading to the courts, the family decided to liquidate Wealth4u, transferring its assets and rights to concession 10 into African Dune Ltd, owned outright by Pina.

Investors who poured more than R100-million into Wealth4U were concerned that the assets of a multimillion-rand company, including the valuable concession 10, were now the property of African Dune, officially bought on auction by Pina for the rock-bottom price of slightly more than R2-million.

But even with his legal position now shaky, Liebenberg remained excited at the future business possibilities. He thought he had taken all the necessary steps to protect himself.

“We wrote an agreement that was kept in the office safe,” he said. “If you get to know Afrikaners, we are very trusting. We believe you. We still do business with a handshake.”

Pushing north

He was confident of his contacts in the mining world, which Pina and the Ferrante family needed to enter the diamond trade.

From mid-2009 until the end of 2010, the Ferrante-Liebenberg partnership appeared only to expand. The Italian family wanted to trade diamonds with as many African countries as possible.

And so the South African trader decided it was time to open up his little black book of contacts and bring the Ferrantes properly into the business. Meetings were organised with key functionaries in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Angola.

Preliminary deals were also struck in Zimbabwe, where the Marange diamond fields were still under a Kimberley Process sales ban because of violence there.

In January 2011 Messicati Vitale visited Zimbabwe with his cousin, Salvatore Ferrante Jnr, and a group of Swiss and Bulgarian bankers.

They were cementing connections for the Zimbabwe Diamond Opportunity venture, and scouting for other deals.

Back in South Africa, Messicati Vitale was introduced to Liebenberg by Pina, who referred to him as “our cousin, Tony”.

“He stayed with Pina and me for a whole month,” Liebenberg said. “He wasn’t fluent in English but could understand. He brought lots of expensive gifts from Italy to the family. I only got to know what Pina told me about him: that he was her cousin and had lots of money. I only discovered later, in the press, that he had been jailed for Mafia.”

It was during this month that Messicati Vitale returned to Zimbabwe, this time to Marange. He came back with one million carats of illegal diamonds, bought with cash.

Marange’s diamond prices vary significantly according to the gems’ quality, colour and purity. The minimum set price is $70 a carat, though it is possible to access the highest quality stones, costing up to $450 a carat, “if buyers specifically request it and get it direct from mines”, said a source familiar with the trade.

When Messicati Vitale left Zimbabwe in January 2011, he left with between $70-million to $450-million worth of illegal diamonds.

Where these diamonds are now is speculation, but many of them likely to have made it on to the fingers and around the necks of rich Europeans, who are unaware that their expensive purchase is tainted with blood and Mafia money.

Only a few years after joining Liebenberg, the Ferrante family was well-connected in the DRC, South Africa, Angola and Zimbabwe. There was a steady flow of cash coming in from Europe. But the money, Liebenberg discovered, was not flowing into the African Dune company’s bank accounts as expected. Instead, the cash was funnelled into a new company, Mpreaso Mining, set up by the Ferrantes without Liebenberg’s knowledge.

That meant that the Zimbabwe Diamond Opportunity was now pretty much a dirty venture for the Cosa Nostra, whose own money originates from violence, drugs, extortion and other illegal activities.

On March 2 2011 a diver drowned during the preliminary exploration dives in the shallow waters of South Africa’s concession 10 site. Alberto Ferrante, one of Salvatore Ferrante jnr’s brothers, was in charge of the dive.

The investigation that followed stopped all further explorations on the concession site, and De Beers, which owned the land on the coastline where the ports and warehouses were based, locked African Dune out, effectively preventing the work from continuing.

Liebenberg fired Alberto, but this was, in his own words, “the biggest mistake of my life. I never thought if you fire one the whole family will turn against you.” From then on the Ferrante family’s main focus was to the get rid of Liebenberg.

“At this point, it seemed the Italians were not interested in working the concession,” he said. “They were, rather, only interested in buying and selling diamonds.” It was clear Liebenberg had been used as a gate to Zimbabwe, mainly, and that concession 10 was not their priority.

With enough time and money, the West Coast project could have been lucrative. But the Mafia is averse to risk, and most likely pushed the Ferrantes for quicker investments. Diamonds are commodities, bought and sold quickly as way to clean money. And, in this regard, Zimbabwe was far more important.

Open war

With the firing of Alberto from the concession 10 operation, it was soon open war between the Ferrante family and Liebenberg and, at the beginning of 2012, Pina’s and Liebenberg’s romance came to an end. But when Pina heard he was seeing other women, she convinced him she could not live without him, he claimed in an affidavit prepared for the tangled legal battle that would later follow.

On May 16 2012 Liebenberg agreed to let her visit him at the flat they had once shared, above the offices of their cutting shop in Johannesburg. The two had sex but, while Liebenberg showered, the police arrived. Pina had accused him of rape. “I was arrested and kept in jail for 11 days,” he said.

Liebenberg claims that, during that time, the Ferrantes took the diamonds and the written agreement on the real ownership of Liebenberg’s assets from the office’s safe. He was left with nothing and, at that point, he said, “they owned me”.

According to the affidavit, the Ferrantes also changed the registration numbers of all the cars that belonged to Liebenberg. “I had no control over my office, my papers, my videos,” he said. “I had filmed every meeting, but now I have no proof of anything; my computer is still there. And, in the meantime, they began selling all the assets.”

Liebenberg was found not guilty of rape. He claims that he was physically intimidated by Pina’s new man, the head of a private security firm in Pretoria.

In March 2013 Liebenberg decided to drag Pina into court to reclaim his assets. The legal battle is ongoing.

He reports he still receives death threats over the phone from people connected to the Ferrantes, who seem unperturbed by the Liebenberg lawsuit. The family’s business keeps on going, becoming more stable and profitable than ever, spreading over Zimbabwe, the DRC, Angola and Ghana – all of Africa’s most important diamond centres.

Both Pina and Salvatore Ferrante jnr refused to comment.

Silence has served the Mafia well in the past, but Messicati Vitale and the Ferrante family have a potentially huge headache: Palazzolo.

Sicilian prosecutors consider the information locked in his head to be crucial, capable of implicating state officials and powerful business-people in Germany, Switzerland, the United States, and large swathes of the African continent where he worked his way to the top, acquiring political and economic power, in some cases at the very highest levels.

In South Africa, Palazzolo could describe, if not the latest Mafia business ventures initiated since his arrest, then the structures and channels on which they were built.

Palazzolo is jailed under the infamous “41bis” regulations for Mafia bosses: isolated and alone in a cell of only a few square metres. He cannot correspond with the outside world and cannot receive visits. Even his “hour of air” is spent alone.

And this is how Palazzolo will face the next eight years – unless he talks. – Additional reporting by Khadija Sharife, Craig Shaw, John Grobler

This article draws on an investigation by the nonprofit Investigative Reporting Project Italy (IRPI) and the African Network of Centres for Investigative Reporting (ANCIR), with the collaboration of the data analysts of Quattrogatti and with the support of German nonprofit investigative centre Correct!V. The project was made possible by the Innovation in Development Reporting Grant Programme operated by the European Journalism Centre, with financial support from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and a grant for investigative journalism from Journalismfund.

Inside the Palazzolo empire

In Italy, after a Mafia boss gets convicted, the authorities trace and seize his assets because the only way to really have an effect on mafias is by getting at the money.

In the case of Vito Roberto Palazzolo, the task is particularly difficult.

He sits on an empire of diamonds, luxurious properties and billions stashed offshore.

And he has an army of proxies securing all assets from confiscation. These assets have been mapped for the first time in new research by a group of European and African investigative centres.

The picture that emerges, once the web is untangled, is of a thriving empire. Property owned or controlled by Palazzolo is typically owned by companies in countries such as South Africa and Namibia, with those companies in turn owned by trusts or offshore entities.

Through various mechanisms Palazzolo, his family and individuals that Italian police consider his proxies can be shown to control or to have previously controlled four farms in Namibia (totalling some 34 000 hectares worth about R24-million) and a web of 46 companies that control 70 properties worth just shy of R500-million.

The South African properties include:

- A Plettenberg Bay stud farm;

- The La Terra de Luc estate in Franschhoek, where La Vie de Luc branded spring water is bottled;

- The San Michele villa in Bantry Bay;

- Apartments on Cape Town’s V&A Waterfront, complete with private docks for yachts; and

- Properties on Shortmarket Square, a stone’s throw away from Parliament.

The heart of the Palazzolo empire lies in the secretive corporate jurisdiction of the British Virgin Islands.

Through five innocuously named companies registered there, Palazzolo obtained shares (since sold) in the largest diamond mine in Russia and controls Avila and Marbella, two Namibian diamond-cutting companies headed by his sons and his Namibian partner, a sightholder in De Beers and a son of a Namibin leader. – Additional reporting by John Grobler, Khadija Sharife and Craig Shaw. Data analysis by Stefano Gurciullo