Japan sells Africa its second-hand cars rather than recycling them.

COMMENT

Batswana love their cars and, regardless of the size of their pay packet, they will proudly drive their cars to work on the ever-more congested roads – even if they have not had enough money to service them since the late Jurassic period.

There is perhaps no other country where the private sector so completely dominates transport. In most cities, national or local government provides some form of public transport, but not in Gaborone. The last form of public transport was the Botswana Railways commuter train system, but it could not make a profit and closed many years ago.

The options now are either shared private transport such as the use of minibus taxis or, increasingly, privately owned second-hand cars, commonly derogatorily referred to as Fong Kongs. They are imported from Japan, the United States and the European Union, and can be cheap, sometimes selling for as little as $1 000.

That, of course, is the price in Japan, and you have to add to that the cost of transport to Gaborone, high import duties (up to 28%) and 12% to 16% value added tax (VAT), depending on the Southern African Customs Union (Sacu) country.

The fact that the taxes are so high provides a considerable incentive for importers to undervalue the vehicle. Getting a false receipt is easy – you just ask for it.

In theory, the customs union could use an international reference, such as the Blue Book, which gives you a list of prices and values of cars. But customs officials know that the cars being imported are being undervalued.

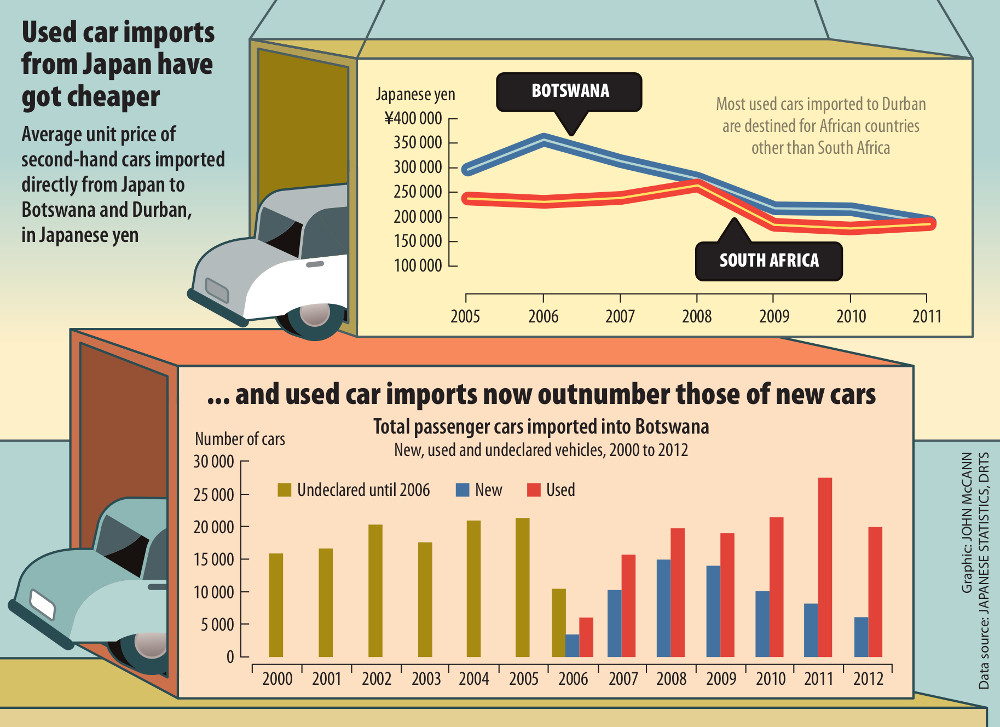

It is difficult to know exactly how many second-hand cars Botswana is importing and what their value is because the statistics do not readily differentiate between the import of new and used vehicles.

Moreover, you cannot tell accurately from the export figures from source countries because so many of the vehicles entering Botswana go to the bond in Durban first and are bought there.

The bond is a strange place and you have to have a foreign passport to enter it because South Africa long ago banned the import of second-hand cars, knowing the damage it would do to its highly protected and subsidised automobile sector.

But, based on Japanese statistics, the number of vehicles exported to Botswana is growing exponentially, from 3 000 a year in 2007 to more than 8 000 a year in 2012.

Of course, much of the Japanese data does not include vehicles under about $2 000 and much of the data excludes what Africa is buying.

In 2014, Japan exported more than one million used vehicles and about 15% to 20% went to Africa.

If one is young enough to believe the trade statistics, the unit export value of the cars entering the bond in Durban, and then into Botswana, are becoming lower each year.

This could be because the exporters and importers are evading import duties and VAT, or it could be because the market for these vehicles is becoming more closely targeted at low-income groups. The export values might also be declining as the global second-hand market becomes saturated with more developed countries either subsidising the sale, or increasing the export, of old cars.

For Japan, the US and the EU, the second-hand market, although not significant, is an important way of disposing of older vehicles. Their governments have, since the 2008 financial crisis, provided economic incentives for people to get rid of their used cars to stimulate domestic production.

The US under President Barack Obama had the “cash for clunkers” programme but this is only the tip of the iceberg in terms of incentives that governments have given to get rid of used cars and to stimulate consumption of new cars. Developed countries are developing their electric car markets, which is providing a huge incentive to their domestic producers.

So what do you do with the junk? Export it.

Japan has the most sophisticated incentive system to get its citizens out of their motor vehicles that are three to six years old. After three years, every car has to pass a roadworthy test, which, in some cases, costs up to $1 000 – and that is without the repairs that are needed. This creates a considerable incentive for the Japanese to get rid of their ageing cars.

But the Japanese have another problem. In other countries, the biggest second-hand market is usually local buyers. But the Japanese have a cultural aversion to buying anything second-hand. So the Japanese government has organised a first-rate export certification system, which has led to the development of a multibillion-dollar used vehicle trade.

The biggest markets are Russia, Chile and the United Arab Emirates. The fourth biggest is South Africa – that is, Durban – from where the vehicles are distributed to Africans other than South Africans.

The South African ban is to protect local manufacturers but, ironically, those who pay the price for this protection are the citizens of the Sacu countries that import used cars.

The South African industry receives tariff rebates from the customs pool, which would otherwise go to the four other small Sacu states – Botswana Lesotho, Namibia and Swaziland. The main countries subsidising the South African industry are Botswana and Namibia, which each lose about R5-billion annually from customs revenue.

But the growth of these second-hand cars are an economic disaster for much of Southern Africa. Because the use of roads is free and second-hand cars are cheap, the growth of the market is distorting the development of infrastructure. Small cities such as Gaborone now have four-lane roads to accommodate the flood of second-hand cars, which is taking up the scarce funding that should be used for rural roads and infrastructure.

Africa is accepting scrap cars, and those importing them should pay for the environmental costs. A substantial scrapping tax should be levied on all imported vehicles, which would rise from, say, 1% for new cars to 40% for the oldest, biggest engined used cars. This should be based on book values because undervaluation is so pervasive in the market.

The levy could be used to subsidise the VAT and import duties on minibuses in the short term and to reintroduce low-cost commuter railway services in Gaborone and other cities.

This sort of cross-subsidisation would also have a dramatic effect on the galloping land prices in Southern African capitals. Gaborone and its increasing congestion is proof that the free market cannot solve all the nation’s problems and that an effective public transport system is needed.

But there is much bigger policy issue at stake in the Fong Kong trade. The importation of second-hand vehicles, like that of second-hand clothing, is emblematic of Africa’s place in the global value chains.

West Africans once produced some of the world’s finest cloth but now Europe dumps its discarded clothes in Africa and Japan sells us their second-hand cars rather than recycling them.

This the Europeans and Japanese do in the name of energy efficiency, but they are exporting their energy inefficiency to the developing world. In the long run, the used vehicles will produce even more pollution because Africans, often with unsafe, poor or no public transport, will keep them for much longer than the Europeans and Japanese.

Africa will continue to produce nothing more than holes in the ground – it will sell ever more minerals to Asia and the EU to pay for ever more cheap cars, which, in turn, will be made from African minerals.

Is this ever to be Africa’s place in the global value chain?

These are the views of Professor Roman Grynberg and not necessarily those of any institution with which he is affiliated.