The Chinese government has put its iron ore producers on life support as global oversupply continues to see the metal lose value. Now the pressure is mounting on high-cost producers who have begun to pull the plug on operations, and major mining companies in South Africa and elsewhere have been forced to take a harder look at costs.

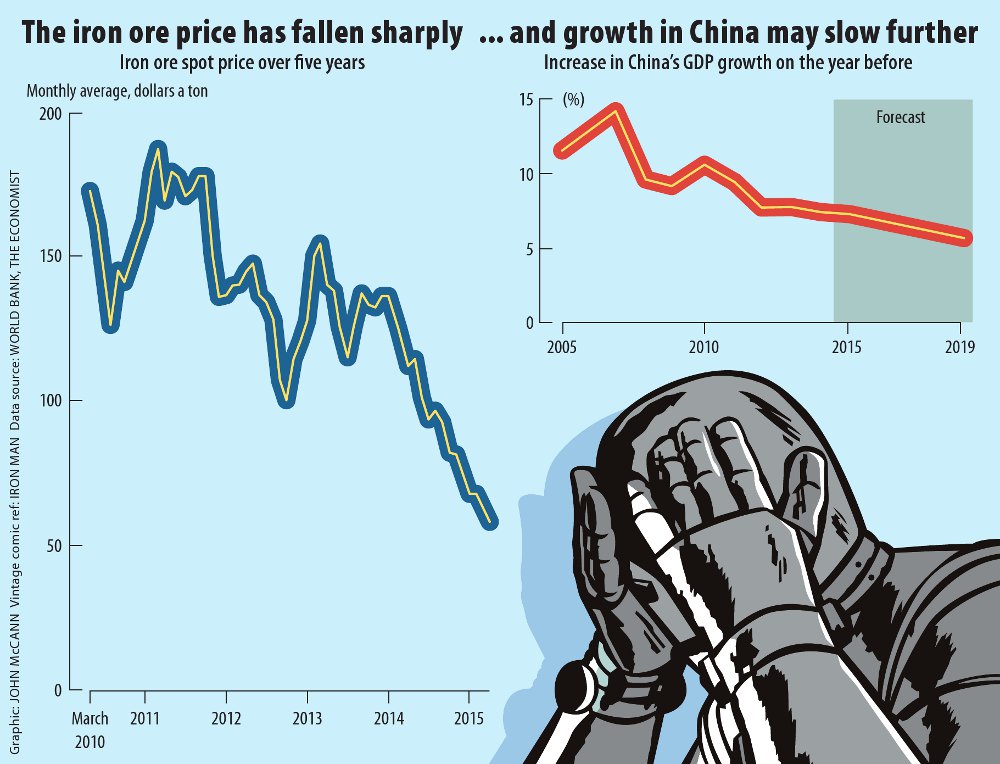

The iron ore price has dropped to a 10-year low of $47 a tonne in early April as a result of waning growth in China, the market that drove the demand for iron ore, a key component in steel, and the biggest iron ore-producing nation in the world.

The Chinese economy grew by 7% in the first quarter of the year, its slowest rate since it felt the effect of the global economic recession in 2009. As a result, the global glut in iron ore supply is expected to balloon to 163-million tonnes in 2015, up from 52-million tonnes in 2014, according to a report published by Goldman Sachs in September last year.

The bank also predicted a surplus of 245-million tonnes in 2016 and 295-million tonnes in 2017.

According to a Reuters report, a third of China’s iron ore mining companies had stopped production by January this year, while major mining companies have continued to feed metal into the oversupplied market.

But, from May 1, the Chinese government will reduce the ratio of the iron ore resource tax from 80% of the original standard to 40%.

Nothing to do with profits

Kevin Ng, a tax partner at Deloitte’s Beijing office, said China’s resource tax had nothing to do with profits but was a levy on the amount of metal or mineral mined.

“The Chinese government does not want the industry players to overmine the resources, so it tries to make use of the resources tax to control exploitation of the mines,” Ng said. “Currently the rate applicable to iron ore ranges from $0.30 [two renminbi] to $5 [31 renminbi].

“To what degree an operation is taxed is at the government’s discretion,” Ng said, adding that the complexity and costs of each mine were taken into account.

Before, the government would charge up to 80% of the maximum tax per tonne, but had recently announced this would be adjusted downward to 40% of the maximum.

According to a note published by Mysteel, a leading iron ore and steel industry information and consultancy service, additional relief was granted in the form of lower electricity costs at off-peak times, but that “will have very slight impact on alleviating their cost pressure”.

Loans and directives

Tim Murray, the managing partner of the Beijing-based consultancy, J-Capital Research, said he expected that further “real subsidies to domestic iron ore mines will be access to low-cost loans to cover losses and or directives to state-owned steel mills to buy domestic iron ore”.

Days before China’s announcement, Australia, the world’s second largest iron ore-producing nation, also announced temporary relief, which would allow junior mining companies to defer royalty payments to 2016.

“Anything that helps that industry at this point is going to exacerbate the oversupply. Even if they keep one mine open or just one guy working, it is going to keep oversupply,” said Peter Major, a mining analyst at Cadiz Corporate Solutions.

China might be the world’s largest producer of iron ore, but its quality is poor and production costs are high because mines are often far inland and a long way from ports and steel mills.

“The thing with this tax relief [is it] will keep mines alive that should have closed down,” said Troye Brady, an analyst at Noah Capital.

Captive producers

But, he said, the largest iron ore producers in China were typically state-owned enterprises, which were captive producers supplying particular steel mills.

“I think this [subsidy] is to soften the blow. China wants to kind of nudge them into other industries, instead of having blood in the streets,” Major said.

He said that up to a point, it made sense for the Chinese government to subsidise mines that created many jobs.

“It [the subsidy] might prevent some closures in China, maybe those guys who are marginal. [But] at today’s prices, I doubt they have one economic producer in the country,” Major said.

Mysteel, in its note, said: “Resource tax reduction and electricity subsidies give a relief for domestic iron ore miners, but will not basically improve their current status quo, and closed mines wouldn’t possibly return to the market because of this.”

Meanwhile, higher cost operations around the globe continue to fold.

Suspended operations

Most recently, on April 10, Atlas Iron, producing an average 12-million tonnes a year, suspended operations.

“Despite an extensive cost-cutting programme, to which staff and contractors have made significant contributions, the global supply-demand imbalance for iron ore has driven prices down to the point where it is no longer viable for Atlas to continue production,” the company said in a statement.

Just days later ratings agency Standard & Poor’s placed eight major iron ore producers on “credit watch negative”, including BHP Billiton, Rio Tinto, Vale, Anglo American (the majority shareholder in Kumba Iron Ore) and Exxaro Resources.

Brady said producers should be cutting back on production but were instead continuing to feed into the oversupply.

“The Chinese are quite high on the cost curve. Logically they should be cutting production … [as to who will be the first to cut] it’s now a case of who blinks first,” he said.

Slowed expansion

Not so much a blink as a twitch – last week on Wednesday Billiton, the world’s third-largest iron ore producer, said it would slow down its operational expansion in Australia.

The news evoked a positive response from the market, which pushed the metal price up to $60 per tonne this week. The share prices of Billiton as well as that of its two biggest competitors, Rio Tinto and Vale. In South Africa, Kumba Iron Ore saw its share price rise from about R130 a share last week on Wednesday to R175 early this week.

If Billiton is feeling the heat, it’s a fair assumption that Kumba, the owner of Sishen, the largest iron ore mine in Africa, is feeling it five-fold.

“To uncover the real rich ore, Kumba have to move five or six tonnes to get one tonne of rock. It costs you the same to move a tonne of waste as it does to move a tonne of ore. So the rock moving costs are five times as high as the ore moving costs,” Major said.

Although costs could go up as fast as the metal price, they didn’t come down nearly as quickly, Major said.

Indeed, when prices soared to highs of more than $180 a tonne in 2011, Kumba’s share price rocketed to R500 a share. According to its annual reports, production for that year was 41.3 megatonnes, bringing in revenue of R48.6-billion and resulting in operating profit of R32-billion. In 2014, production rose to 48.2 megatonnes, bringing in revenue of R47.5-billion and operating profit of R19.19-billion.

‘Cost heavy’

“Kumba has become very inefficient; it is cost heavy,” Major said. “I bet their costs are close to $45 a tonne. I bet, right now, as it stands, they are breaking even.”

He said the weak rand would have helped the company “but they will have to get those costs down fast”.

Major estimated Rio Tinto was now producing iron ore at a $17 a tonne, and could keep that up for a decade. Billiton was similar and even Vale could get cost below $30.

In its quarter production and sales update, released last Thursday, Kumba said the weakness in the metal price had necessitated a review of its business.

“A number of actions have already been implemented, [and] further initiatives are being taken to reduce capital expenditure and lower the cost of production.”

Small impact

Timo Smit, Kumba’s head of marketing and sales, said the reduced resource tax for Chinese mining companies would aggravate the challenges facing the industry, although only to a small extent. “We don’t think the impact will be massive.”

Smit, speaking by phone from Singapore, said the effect might be a cost saving of $2 or $3 a tonne for China’s domestic mining companies. This was unlikely to have any effect on state-owned entities. “They will continue producing regardless.”

Small, private mines would, however, be more competitive as a result.

“But if we look at how many of those will be margin positive because of this subsidy, it’s perhaps not even a million tonnes … In the greater scheme of things that is absolutely nothing,” he said.

“Kumba has always faced the difficult situation of being further away from China. It’s a natural disadvantage we deal with.

“And the Sishen pit is getting deeper and bigger. Obviously that is also having a cost impact.”

Competitive edge

Smit said Kumba had a competitive edge because of the very high quality of its iron ore. Another advantage was that two-thirds of Kumba’s production consisted of lump ore, which fetched a premium in the market, although this was extremely variable. “At the moment, the premium is about $10 a ton. That’s an additional $6.5 to $7 on every tonne we sell.”

Smit said Chinese crude steel production had grown by 6.5% in 2013 and 4.5% in 2014. This year, it was expected to increase by between 1.5% and 2.5%.

“Sadly, we don’t think there is anything on the horizon that suggests Chinese steel production will pick up again,” Smit said.

“We have seen the China central bank cut reserve requirements on commercial banks by 1%, which does release liquidity, about 1.2-trillion renminbi … Obviously that has a good impact on commodities, but clearly there was a need to announce such a stimulus package.”