Stanlib chief economist Kevin Lings says cash in hand is an indication of firms' profitability.

The private sector remains reluctant to invest the cash lounging on company balance sheets. Poor confidence in the economic environment has played a notable role in this, but the picture may be more complicated than it first appears.

Large corporates, in particular, have been aggressively managing costs to help sustain relative profitability while maintaining a business- as-normal approach, according to an economist.

This week Statistics South Africa published the quarterly financial statistics of the private sector.

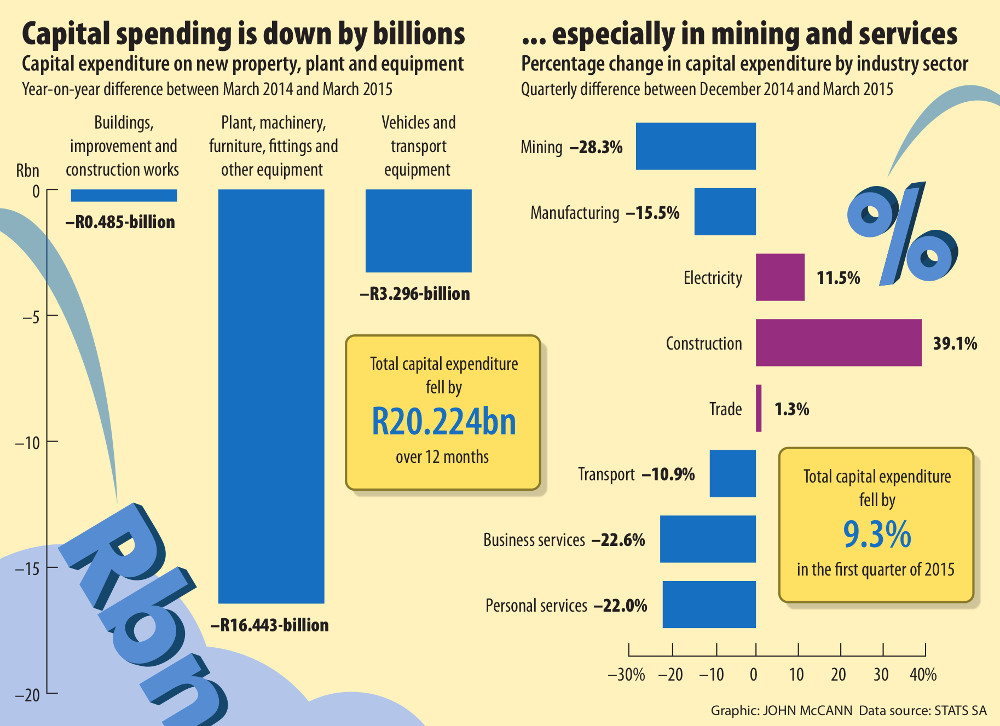

It revealed that capital expenditure fell 9.3%, or almost R9-billion, between the last quarter of 2014 and the first quarter of 2015. Year on year, the drop was a much larger – 18%, down by more than R20-billion.

The report reviews more than 5 000 private enterprises but excludes financial mediation and insurance, agriculture, forestry and fisheries, as well as government institutions and municipalities.

On a quarterly basis, mining and quarrying was down more than 28%, and manufacturing declined by 14.5%.

Only a few sectors, namely electricity, gas and water supply, and construction, saw an increase in capital expenditure.

Electricity, gas and water supply was up by more than 11% during the quarter and construction rose by almost 40% in the same period.

But year on year, the electricity, gas and water sector saw a sharp decline – more than 27%, or R7-billion.

Capital expenditure includes not only new investment but also money spent on the maintenance of plant and equipment.

According to Krisseelan Govinden, a manager of private statistics at StatsSA, the quarterly increases seen in the electricity, gas and water sector have been driven mainly by the large construction projects of Medupi and Kusile, the two power stations being built by Eskom.

The construction of the country’s renewable power projects also contributed to some extent to the increases.

The increases in the construction sector’s capital expenditure was driven by an increase in plant, machinery, furniture, fittings and other equipment, as well as vehicles and transport equipment, according to the report.

The large fall overall in capital expenditure year on year could be related to the economic climate, resulting in companies investing less, Govinden said.

But the executive manager of private sector statistics at StatsSA, Sagaren Pillay, cautioned that capital expenditure by the private sector was generally volatile, as it was not governed by seasonal cycles and each company would take investment decisions individually.

The perception that companies are hoarding cash and unwilling to invest applies to much of the globe.

The Financial Times reported this week that Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe had called on Japanese corporates to spend the nearly $2-trillion held in corporate cash and deposits to help to re-energise the country’s flagging economy.

Abe’s call followed a report of findings by Deloitte that the world’s largest non-financial firms had accumulated cash reserves of $3.5-trillion by the third quarter of last year.

Corporate cash reserves in South Africa have reflected this trend.

Amber Morgan, the head of institutional sales at Investment Solutions, said corporate cash balances had been rising steadily since mid-2010.

According to data from the South African Reserve Bank, as of December 2014, corporate cash balances had reached R1.35-trillion.

The amount was the equivalent of 38% of South Africa’s gross domestic product, she said.

“Companies are waiting for a less uncertain outlook to start investing,” she said.

Kevin Lings, the chief economist of Stanlib, said cash in hand was also an indication of the firms’ profitability.

In South Africa, large businesses, in particular, had been reporting relatively good earnings and good profit margins, and held relatively low levels of debt.

This raises questions about why South African firms have been reluctant to invest.

Lings said poor business confidence was the simple answer, and a number of things contributed to this.

Many companies had done well, not because they had seen increased demand for their products but because they had managed their cost svery well.

This often meant companies had managed their employment base. After the 2009 recession, many firms had not replaced the one million people who had lost their jobs.

Lings cited the example of the local manufacturing sector. According to Reserve Bank data, it had experienced steady increases in production since 2009 – alongside a continued reduction in employment.

“Even with low levels of activity, you can still make lots of money if you are reducing employment,” he said.

Corporate South Africa also had to consider the power problems facing the country when taking a decision to expand. “Electricity is a very clear and obvious constraint,” Lings said.

But a “business as usual” culture was emerging, reflected by the relatively low levels of research and development and innovation in new production and technology design.

In large part, this was because of the structure of many industries, which were fairly concentrated and dominated by a handful of players.

“It’s not particularly competitive in some sectors,” he said.

When this was added to more general concerns about policy uncertainty over issues such as land and the volatility of labour relations, it provided little incentive to these firms to invest or innovate.

This further contributed to comfortable balance sheets and happy shareholders, who were unlikely to question companies’ strategies as a result, he said.

A shift by the public sector and government to reprioritise its spending, moving it from consumption to infrastructure, could be a catalyst that could change this situation, Lings said. It could encourage corporates to begin investing again.

“But, unfortunately, a lot of the promise that was put forward by the government in terms of the infrastructure [spend] has not materialised,” he said.

“Most projects have fallen away or fallen behind, budgets have had to be scaled back.”

Unless there were material changes to these circumstances, such as an improved electricity supply, business confidence was unlikely to improve or to trigger any significant investment, he said.

Loans picking up – slowly

Indicators such as private sector credit extension, released this week by the South African Reserve Bank, have shown an uptick in the credit granted to the corporate sector. But this growth is not a sign of greater investment by the private sector, say economists.

Loans to companies grew by 14.4% from a year ago, according to Nedbank’s economics unit, although this rate slowed from the 15.1% recorded in April. Credit growth to households was a muted 3.2%, down from 3.3%, it said in a note. The continued challenging environment would keep firms cautious about committing to large expansion projects, it said.

Stanlib chief economist Kevin Lings said the increase in corporate credit reflected commercial property development, notably in central Sandton, growth of renewable energy projects and the local funding of business operations in the rest of Africa. But it did not reflect a rise in private sector fixed investment, which it was expected to slow, given the lack of capacity expansion, he said.

It might also reflect distressed borrowing on the part of small businesses.

“When we look at balance sheets, big business is doing well. Small business on the other hand seems to be struggling,” Lings said.

Small firms were hit harder by strikes, blackouts and xenophobic violence, and usually did not have the cash to tide them over until conditions improved.