Memprow SA mentors Naledi Makasi

“I have been raped twice. The first time I was nine and the second time, by two men, in 2007,” says Tebello Siko, a 29-year-old woman who lives in Langaville, a township south of Brakpan on the East Rand. She is a caregiver for abused girls and young women in the township.

Siko sits on her bed. She is dressed in a red form-fitting cotton dress and a black cardigan. Her bed dominates most of the space in her one-room home. A wardrobe, a TV set and a two-plate stove take up the remaining space.

She recounts the rapes by counting on two fingers of her left hand. “When you are nine and something like this happens to you, you go to your mother,” Siko says. But in her case, it was to no avail. Her perpetrator disappeared, but she saw him again when she was 13.

“I ran to my mother so we could open a case. But my mother went to the guy and asked him for money. They signed some sort of agreement on a letter. I didn’t tell my mother at the time, but I saw that letter,” says Siko.

She points at her second finger, takes a deep breath and looks up at the ceiling. In 2007, the second rape happened. “I knew to report the case but I didn’t.” Siko says she felt empty and she blamed herself. She thought she deserved to be raped and she even waited for it to happen again.

No support structure

“I thought, why not a third time? Ngiya zinyanya [I was disgusted with myself].” She places her hand on her chest and shakes her head. Siko says she had no support structure, which is why she approached Sithand’Izingane, a nonprofit organisation in her township, where she is now a caregiver.

The project was started in 2000 by the women of the St Paul and St Martin de Porres Catholic Church and is situated in Withok, opposite Langaville.

It is a daycare facility. Primary and high school children also go to the centre every day where they are taught life skills. When they arrive, they are given a plate of hot food and for most children in the area, this is the only meal they get.

Sithand’Izingane’s manager, Thembi Aphane, says the care project was started because of the high rate of unemployment affecting many households in the area. Most people go to bed without food, and are without other basics such as water and proper sanitation. This breeds anger among the adults, who turn to alcohol and drugs as a distraction, Aphane says.

This cycle of poverty and alcohol dependency usually leads to high crime rates, domestic violence and the rape and the abuse of children and women. “The majority of the women in this area still depend economically on their husbands or the fathers of their children and have little to no knowledge about their rights,” she says.

Sithand’Izingane recently started collaborating with Memprow SA, a nongovernmental organisation that focuses on mentoring and empowering young women. (See below, “You can change your stars if you want to”).

“I think Memprow is good. When I was nine, I needed it most. It is different because it is based on women. I used to say to myself I am not valuable. I have never thought of what my values are so that I could know when to say no. It [Memprow SA] teaches you to be assertive,” Siko says.

Foster care

One of the young Memprow women is 18-year-old Jabulile Mtshali. She and her three younger siblings were being raised by their grandmother, who died in 2013, leaving Mtshali, then only 16, to take care of her two brothers and sister. The four are now under foster care and share a house with 20 other people.

It smells of cooked tripe as we enter the house. None of the doors have handles. The carpet is dirty, which makes it hard to tell what colour it used to be. Mtshali takes us down the passage and opens a bedroom door.

It is 4pm on a Monday and she is still in her school uniform. Her tie is fitted neatly beneath the collar of her blue school shirt. Her blue school socks are pulled up below her knees and her shoes are polished. She sits on the bed.

The wardrobe door is broken. Inside, blankets are thrown in on top of clothes, shoes and some broken toys. Her other school shirts are ironed and placed on hangers on the curtain rail. Below the rail, on the mat, are shoes of different sizes.

“We all sleep in this room on the floor. More than 10 of us. At night we just take blankets, throw them on the carpet and make a bed.”

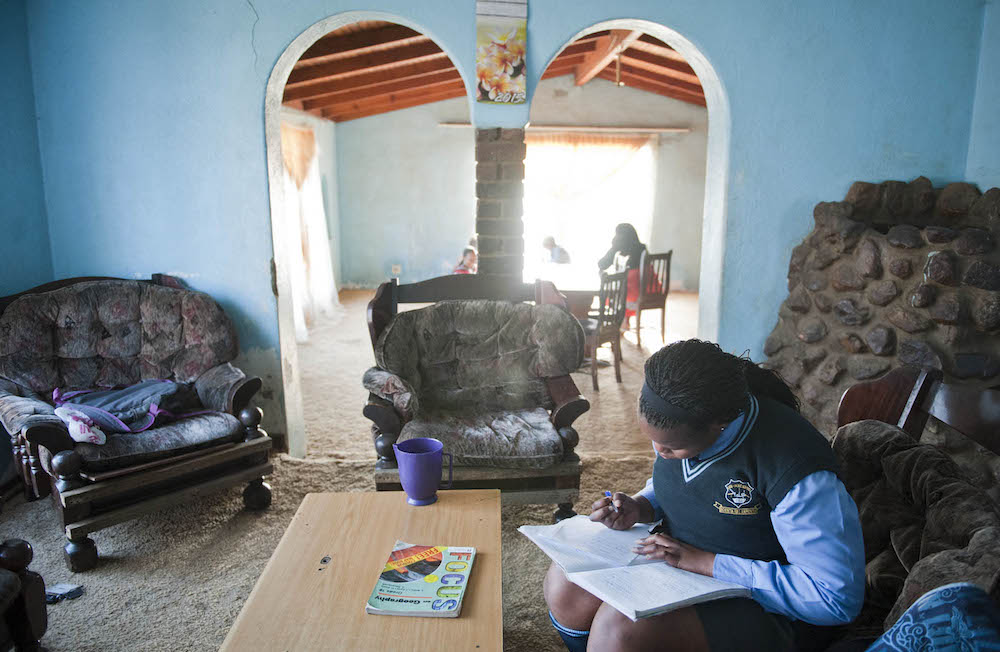

Valuable lessons: Jabulile Mtshali does her homework in the house she shares with 20 other people. (Madelene Cronjé, M&G)

Mtshali says she wants to be a soil scientist, which is why she chose to study science and pure mathematics, something her teachers advised her against. “I want to be a farmer, you know. I will start as an agriculturist and then study further to become a soil scientist,” she says, looking me square in the face.

“This is my life and I have to take care of it,” she says unapologetically. Mtshali says the Memprow SA programme taught her that women are just as smart and as important as men, and that they should determine their own destiny.

“You know what,” she moves her hand up and down to emphasise her point, “women here think, if a man talks, his word is the last decision. But what I have learned is, if you are a woman, you fight for yourself, and you must make your own decisions.”

Mtshali says the programme has taught her to put herself first, echoing the sentiments of Siko, her mentor. Mtshali says she wants to be a Memprow SA mentor so she too can teach young girls in her community about loving themselves.

For Siko, the most important lesson she has learned from the programme is that she is not to blame for her attacks. “You know, here in our community, when a girl is raped, people say, ‘But why were you wearing tight clothes, or short skirts?’ They tell us to get over it because you have sex anyway.

“I have learned that I did not deserve to be raped. I am valuable.”

You can change your stars if you want to

Memprow was started in Uganda in 2008 by Dr Hilda Tadria. The organisation promotes girls’ and young women’s rights and has expanded into Zambia, Zimbabwe and now South Africa.

It focuses on those between 12 and 24 years of age, especially ones from impoverished areas.

Memprow teaches girls and women about sexual and gender-based violence in their communities and at learning institutions. Using mentors from similar backgrounds, the programme also teaches them social survival skills and how to become self-reliant.

Memprow SA executive director Terry Sacco and its programme director, Naledi Makasi, say they brought the programme to South Africa because they wanted young girls, especially from poor communities, to know that they have a future. Sacco says the programme helps girls to question the way “our minds have been colonised by patriarchy and teaches them how to remove the mental barriers people create”.

“We are suffering from profound gender-based violence. We are here to tell the girls that, no matter what your living circumstances are, you can change your stars if you have a clear sense of what you want to do.”

She says her programme has trained caregivers from Sithand’Izingane about knowing and loving yourself, gender-based violence and social intelligence. “We teach them they must be wise in the world. People are out there to rape you. To say you’re beautiful, but they just want to fuck you,” she says.

The organisation’s mentors went through the training at the beginning of August. They learned essential skills, which they will now teach to other girls and young women. Makasi says their programme will teach girls to know their value. “Had I known the things we teach these girls back then, I would have made better choices,” Makasi says.

The official launch of Memprow SA takes place on Friday 21 August. The programme has been started in Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal and will be extended to other provinces. – Thuletho Zwane