Guillaume Rossouw and the Safari Suits had a residency at Cape Town’s Club Tropicana in the 1980s.

The golden era of the live gig has come to an end in Johannesburg. There are no more evenings when you can decide between the Bassline (the real one, not the concert hall), Roxy, Tanz Café, Back2Basics and that place on top of Northcliff Corner no-one can remember the name of. The economy of the DJ and the lack of a TV station that supports homegrown music destroyed this era.

The scene has moved to the fringes. Not the fringes of society, but the fringes of the city. There is a more active live music scene in Fourways and Edenvale than there is in Braamfontein or Melville, traditionally the two places you went for your drinking jol. This may have to do with the migratory patterns of music fans, or the standard suburban fear of coming too close to the dangers of Johannesburg. Whatever the reason, for inner-city music fans, the prospects are bleak.

Westdene’s nightlife is more famous for street drinking and student muggings – and lately the Afrikan Freedom Station – than anything historic. That is left to its famous neighbour, Sophiatown. But perhaps, just perhaps, Westdene could still find a place in history.

That oldish, hippie-looking dude, the one with the greying beard, Prince Valiant haircut and the don’t-fuck-with-me look in the eye, the dude behind the counter at the Bohemian, who may or may not serve you the beer you requested – he may be the saving grace of the live music scene. His name is Guillaume Rossouw.

The original Bohemian kicked off in Richmond in the 1980s. It was run as an after-hours club for entertainers and had a door policy as strict as anything you’d find in New York. It changed with the times, becoming a yardstick for live music in Johannesburg – Squeal, Sugardrive, Nine, Wonderboom and others performed there. But then the building’s new owners, in line with their Muslim faith, did not want alcohol sold there and ended the lease.

Bohemian’s face-lift

The new Bohemian reopened in the old Back2Basics space, across the road from the University of Johannesburg. Rossouw is in charge and things have changed already. The infamous pillar right in front of the stage has been removed, for one thing. What most punters don’t realise is the long walk this man has had through South African music.

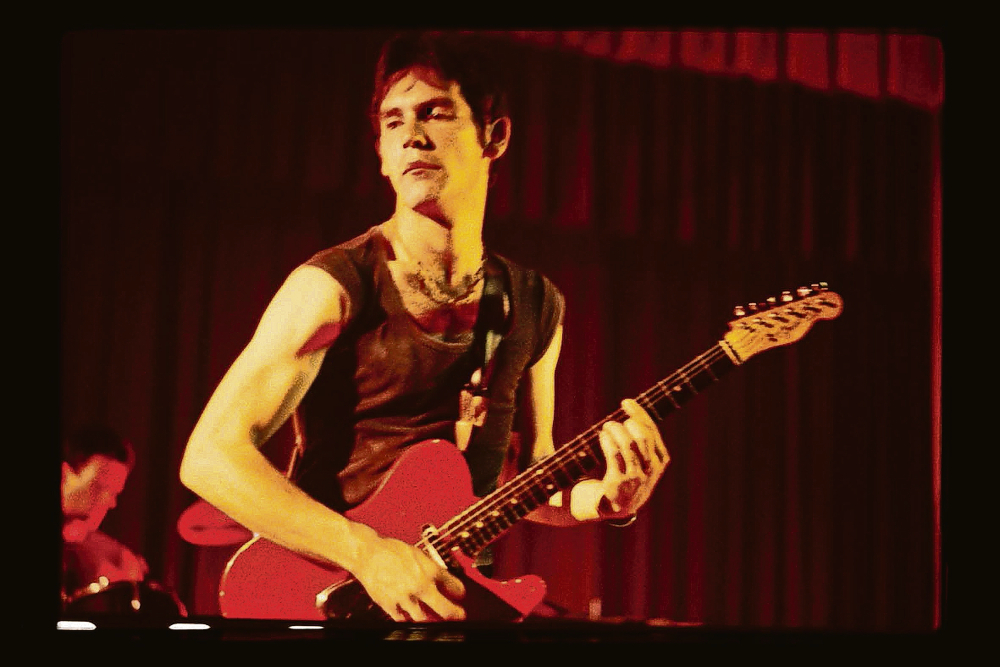

Guillaume Rossouw. (Barry White)

Known by 1970s punk fans as Gil Gap, this survivor of the 1980s club scene of downtown Jo’burg, Doornfontein and Yeoville, as well as various punk bands, reappeared after a 20-year absence, putting to rest rumours of acid burnouts, psychiatric hospitals and political assassination.

Rumours have swirled around Rossouw since his sudden departure (read overnight disappearance) from the infamous Harbour Café in Yeoville’s Rockey Street after Tony Leon turned everybody into a criminal by making sure no more liquor licenses were issued in Yeoville.

The late 1980s in Johannesburg were a dangerous time. Bouncer gangs were killing punters and venue managers, the Greek and Yugoslavian criminal enterprises were moving in, and the state-sponsored hit squad, the Civil Co-operation Bureau, was finding its feet among those it used to harass.

But it was the police, trying to break up the scene, who spilled the most blood. Running the Harbour Café illegally – most venues selling alcohol in Rockey Street were illicit then – meant there had to be a system in place in case the men in blue popped in.

The protest folk scene

Wired on cocaine and drinking on a semipermanent basis, the .22-packing Rossouw had two signs outside his club: “Closed for Renovations” (the daytime sign) and “Private Party” (nighttime). Only if you knew that it was open and could remember your membership number would you be allowed in.

If any unwanted guest got through the security system and ended up inside, a white light went on and everybody started singing Happy Birthday – and got free shooters to maintain the illusion of a private party.

This was not how Rossouw’s parents planned his life. The product of a Broederbond home, members of “all the boards you can think of” and a contemporary of Rika Sennett and Regardt van den Bergh at Hoërskool Linden, Rossouw was supposed to become a lawyer – or perhaps join his brother in right-wing politics.

Instead, he gave it up for music. He started off with his hippy band, Rock Spider and the Screaming Queens. On the protest folk scene, he was taken under the wing of Colin Shamley, who refused to do acid with him because, he said, Rossouw turned into a hairyback when he was tripping.

Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood pushed punk in Britain, and news of it arrived in South Africa soon enough. Cynthia Schumacher, rumoured to be a friend of both McLaren and Westwood, thought she could replicate the success of the Sex Pistols in South Africa with a group consisting of Rossouw and Spider Davies (later to be famous via Via Afrika). Called Scrapnell, the band had various styling and photo sessions, but never played a gig.

Rossouw, our intrepid hippy, had now become a punk. He took the name Gil Gap to prevent the military police from finding him. By this time a warrant for his arrest had been out for a few years; he had ducked his military service. He acted as a punk in a play called Zombie at Cape Town’s experimental theatre, the Space. He paid the rent by working as a barman at an illegal gay club called Anaconda.

The South African punk band prototype

This is where the story of Rossouw’s punk career starts. Starting out with one of the prototype South African punk bands, Safari Suits, he played all the correct political gigs – the End Conscription Campaign, Rhythm Against Detention. He fell out with his bandmates after they accepted a gig as opening act for the Bay City Rollers, which Rossouw could not find it in his dark punk heart to do. In typical punk fashion, there was also a falling-out over who the songwriter in the group was.

Leaving Safari Suits, Rossouw immediately formed Housewives’ Choice and the band got a residency at The Navigator’s Club – yes, you guessed it, a sailors-and-prostitutes bar. Later they got a spot at a gay club called 1886. Housewives Choice were a critical success, but Rossouw left. This time, it was “because they started sounding like the Ramones”.

Then it was the Rude Dementals, with Warrick Sony of Kalahari Surfers on bass. He “was wearing Westwood-type tartan bondage pants when I met him”, says Rossouw. Less than a year later, Rossouw fired Sony. Sony retaliated by painting “I fired the band” on his own van.

Running out of money and with two more mouths to feed in the family, Rossouw returned to Johannesburg. He became involved with Gallant House, a largely forgotten influence on Johannesburg’s nightlife in the 1980s.

Then he started the Pool Club, which hosted the first Afrikaans rock festival, later to develop into the Voëlvry tour of “alternative Afrikaans” acts. Other venues followed, culminating in the Harbour Café and, after a while, Rossouw’s departure from both Johannesburg and the scene.

No covers, no backing tracks

“Too many drugs, too much infighting among the alternative community. Everything went plastic,” he says today. Instead of growing old with his contemporaries, Rossouw started a new life, selling timeshare in the Kruger Park and Mozambique. “I needed nature to heal me,” he says.

He ended up running a restaurant in Komatipoort. Then, he woke up one morning, opened a Facebook account, reconnected with his lost world and packed for Jo’burg.

“Now everything is legal and I have a great support team at the Bohemian,” he says. “I had no idea how many young, quality acts are out there. The Bohemian developed a stigma, deservedly, as dirty and unprofessional. That is all changing.”

His vision for the Bohemian is simple: “No covers, no backing tracks. It’s about the development of art and music. We will get the big names to support the development of the younger ones.”

The Bohemian’s line-up for September includes the Mac Mackenzie Orchestra, with opening act Mnandi Blu, on September 16, 23 and 30. The last Thursday of the month is comedy night. Call 011 482 1725