Picture: Khulubuse Zuma. (Oupa Nkosi, M&G)

The Panama Papers data leak has unmasked the people originally behind a highly controversial Congolese oil deal that was fronted by President Jacob Zuma’s nephew Khulubuse Zuma.

One is South African businessman Mark Willcox, although in 2010 he told amaBhungane that he held no financial interest in the deal, however remote. Willcox was then CEO of Tokyo Sexwale’s Mvelaphanda Holdings, and Sexwale served in Zuma’s Cabinet at the time.

The other is the family of controversial Israeli citizen and diamond scion Dan Gertler, a personal friend of Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) President Joseph Kabila. Gertler’s stake was made public in 2012, two years after the deal.

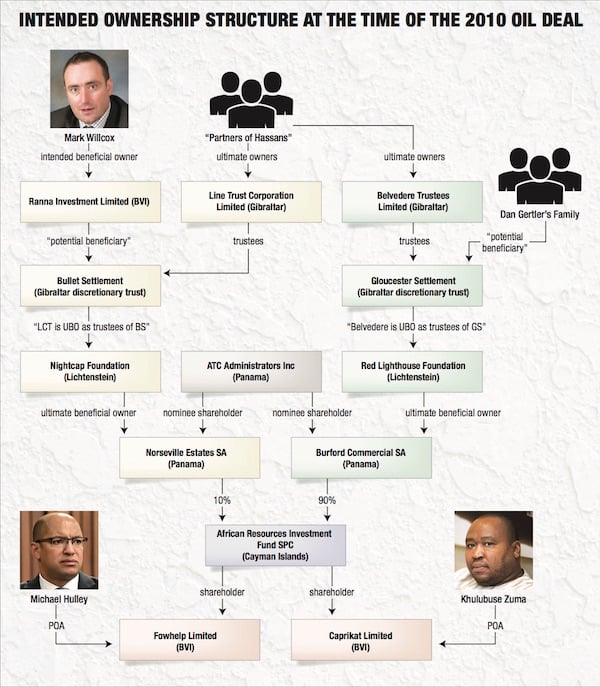

Hidden behind layers of offshore opacity, Willcox and Gertler’s family were intended to be the original owners of Caprikat and Foxwhelp, the mysterious British Virgin Islands (BVI) companies to which Kabila handed highly sought-after oil rights in June 2010, the leaked papers show.

Willcox said this week he never accepted these shares. The evidence appears to support this.

The papers indicate that Khulubuse Zuma held no formal stake, despite his 2010 claim that he was the sole owner.

The political exposure of the deal to Kabila, Jacob Zuma, and Sexwale raised concerns in 2010, but everyone involved denied that the politicians played any role.

“Smash-and-grab”

The Panama Papers do not shed any more light on this. But the high level of ownership secrecy that they show — including the fact that the Panamanian law firm that set up Caprikat and Foxwhelp was long in the dark about the owners — may underscore concerns about political exposure.

Through spokesman Vuyo Mkhize, Khulubuse Zuma declined to answer questions, saying he had no obligation to publicly declare his private business interests.

On Sunday, journalists around the world began to publish a series of exposés based on the Panama Papers, a trove of 1.5-million leaked confidential documents, or 2.6 terabytes of data, from Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca.

The cache was obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung and other media partners.

The documents name politicians, businesspeople, and celebrities around the world who have used bank accounts in offshore tax havens and jurisdictions that offer a high degree of corporate anonymity. In many cases, the suggestion is that these people used the offshore financial system to avoid taxes or hide their wealth, but most deny any wrongdoing.

Included in the documents is emailed correspondence among BVI regulators, Mossack Fonseca, and Hassans, an international law firm in Gibraltar that does business with Gertler’s group of companies.

The correspondence was sparked when Foxwhelp and Caprikat hit the news in June 2010. Kabila had just approved their production-sharing agreement with the Congolese government for the two blocks in Lake Albert, along the Congolese- Uganda border.

Until then, the blocks had been allocated to Irish oil major Tullow. But Kabila’s action had nullified this arrangement and Tullow was furious. It accused Congo of orchestrating a “smash- and-grab”, and questioned the legitimacy of Caprikat and Foxwhelp, which had just been founded and had no energy sector experience.

“… did not havea valid contract …”

This week, Gertler’s Fleurette Group countered that “Tullow did not have a valid contract with the DRC. [It] took Fleurette to court over this issue and lost conclusively.”

Khulubuse Zuma emerged at the time as a spokesman for the two BVI companies. He claimed to own them. AmaBhungane revealed at the time that Khulubuse Zuma had signed the production-sharing agreement on Caprikat’s behalf and that Jacob Zuma’s lawyer Michael Hulley had signed for Foxwhelp.

Hulley did not respond to several messages seeking his comment.

The controversy deepened when it emerged that Willcox travelled to Kinshasa with Khulubuse Zuma and Hulley, and the BVI companies had used Mvelaphanda and Sexwale-linked addresses as their legal domicilium.

Willcox said at the time that he had simply given Khulubuse Zuma “strategic advice” on the deal, but strongly denied any personal financial interest.

About two years later, one of Kabila’s Cabinet ministers let slip that Caprikat and Foxwhelp were actually Gertler’s companies. Gertler did not challenge this, and now openly states that his Fleurette Group owns 100% of Caprikat and Foxwhelp.

According to Fleurette Group estimates, the oil blocks hold reserves of 3-billion barrels. Fleurette says it has spent $100m developing the field.

But while the deal’s political exposure was downplayed, there was panic among Mossack Fonseca’s staff in Panama and the BVI. Email correspondence in the papers suggests that when Mossack Fonseca registered Caprikat and Foxwhelp in March 2010, they did not know that Willcox and Gertler were intended to be their ultimate beneficial owners despite, “know your client” requirements.

And when they learned through news reports that Khulubuse Zuma, a “politically exposed person”, had been granted power of attorney to sign contracts, they considered this reason enough to resign as the companies’ registering agent.

“Perhaps we need to send a clear message …”

Having not received a proper explanation from Hassans, the Gibraltar law firm representing Gertler, one senior staffer wrote to his colleagues: “Perhaps we need to send a clear message that we will not be a dump for dodgy companies.”

When a Hassans staffer wrote back, she sought to ease Mossack Fonseca’s concerns: “I have contacted the lawyers here at Hassans who deal with these companies from this end. They have clarified the situation, which seems to be a case of bad press and sour grapes.”

That same month, Mossack Fonseca’s alarm bells rang over two more BVI companies registered at Hassans’s request: Norseville Estates and Burford Commercial. Apparently they had also failed to do any due diligence on these and did not know who owned them.

The emails flowed back and forth, with apparently frantic Mossack Fonseca staffers setting deadlines for Hassans that were usually not met.

One email suggested the reason for the panic: “It is necessary that the client [Hassans] understands the urgency of this, as in the eyes of the [financial regulator], this info should have been in our offices in BVI…. We are in breach of the obligation to have the info on BVI.”

After several days, Hassans wrote and explained the Foxwhelp and Caprikat shareholding, but only up to a point. The letter described a Cayman Islands investment fund, owned by Norseville and Burford in Panama, whose true ownership was masked by a nominee shareholder, and a chain of beneficial ownership reaching through foundations and trusts in Liechtenstein, Gibraltar, and the BVI.

The letter did not disclose the identity of the real people behind the web.

“… possibility of being fined or our licence being revoked or suspended for noncompliance …”

Having had enough, Mossack Fonseca’s Jennifer Mossack wrote to say it was resigning from Foxwhelp, Caprikat, Norseville and Burford “based on the lack of due diligence information provided by you. We stand the possibility of being fined or our licence being revoked or suspended for noncompliance with the relevant legislation in the jurisdiction of BVI and Panama.”

It was only then that Hassans disclosed that Willcox and the family of Gertler were behind the structure, with 10% and 90%, respectively.

The news came as a relief to one senior Mossack Fonseca staffer: “If these are really their clients, we are speaking about very high-profile and worldwide-known entrepreneurs. The fact that they are doing business in Africa makes their position difficult. We would need to analyse further, but it is good to know that they are not machine guns (sic) criminals.”

By this stage, however, the BVI’s Financial Investigations Agency was asking questions, demanding all due diligence information, particularly in respect of Khulubuse Zuma. A copy of his passport and various bills were passed on.

But the agency still required the share register of the investment fund that owned Foxwhelp and Caprikat. Nearly a year later, Mossack Fonseca complained that this was never received.

According to one final email before it dumped the four Gertler-linked companies, Jennifer Mossack complained: “Hassans has proven to be unco-operative, secretive, and dishonest with us as they hid the identity of their client and are apparently assisting him with his asset protection.”

Willcox says he has never heard of Mossack Fonseca, Norseville, or Ranna Investments, an entity the documents indicate held his intended stake.

“Hassans fully complies …”

His lawyer Rael Gootkin says: “It is possible that it could have been part of Fleurette’s initial structuring to offer such a shareholding to our client. This factually never materialised.”

He says Fleurette approached Willcox in 2010 “to find an industry partner and/or a capital partner to develop the oil blocks”.

In response to questions this week, the Gibraltar firm says: “Hassans fully complies with all local and international standards regarding ownership disclosures and [know your client] practices.

“Details regarding ultimate beneficial ownership was made available to Mossack Fonseca at all times.

“We understand that the only item of due diligence outstanding was the register of members of the [investment fund], which, as explained, could not be provided, as the fund had not been launched.”

A Mossack Fonseca statement says: “Before we agree to work with a client in any way, we conduct a thorough due-diligence process. We follow both the letter and spirit of the law. Because we do, we have not once in nearly 40 years of operation been charged with criminal wrongdoing.”

A spokesperson for the Fleurette group says: “Businesses all over the world use special purpose vehicles in their corporate structures for a variety of reasons. Fleurette uses companies incorporated offshore to ensure tax efficiency.”

Khulubuse Zuma’s role remains a mystery. Fleurette says: “Mr Zuma did have some early involvement as a signatory for the companies, at a time when it was expected that he would have a greater role to play; however, that role did not materialise.”

The amaBhungane Centre for Investigative Journalism produced this story. Like it? Be an amaB supporter and help us do more. Know more? Send us a tip-off.