Most universities were closed for six years during the turmoil and the cult of Mao has persisted into the 21st century.

POLITICS

Youthful idealism is nothing new. A welcome drive for justice emerges in generation after generation of young people, along with the usual personal ambitions.

Contemporary neural science corroborates these tendencies. From puberty until 25 years of age or so, the human brain is a work in progress. It induces young people to seek novelty and excitement, explore ideas, prefer peers to parents and test social boundaries.

The violent demonstrations at South African campuses, triggered by government maladministration, express the frustration of those who cannot afford tertiary education, and also the perennial desire of students to improve the status quo.

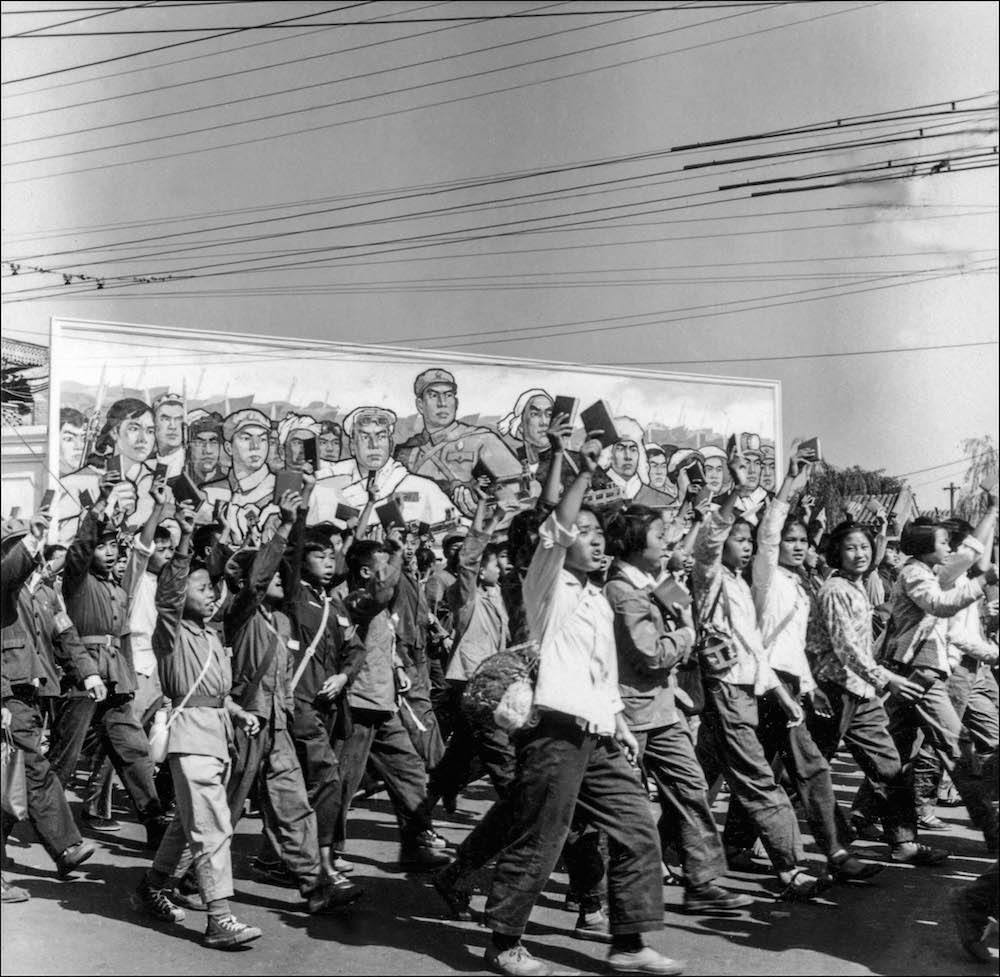

Youthful idealism energised the Cultural Revolution in China from 1966 to 1976. What can we learn from what happened?

A large, neatly painted graffito painted on a wall behind the library at Rhodes University urges the campus to “break the mould” of tradition, religion, injustice, apathy, the colonial and the cultural.

It brings to mind the “big-character” poster written by a philosophy lecturer that appeared on a wall of Peking University in May 1966. It criticised the university administration for being anti-proletarian. Publicised on national radio at Chairman Mao Zedong’s request, it kindled revolutionary fervour in schools and universities around the country.

An editorial in the People’s Daily stated that the aims of “The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution” were to destroy “the four olds” — old customs, old culture, old habits and old ideas.

Thousands of posters appeared on campuses around the country overnight. Most attacked “bourgeois individualism”, “intellectual elitism” and “capitalist roaders”. The attitudes built on Mao’s sustained criticism of nonconforming intellectuals and writers during the early 1960s.

He endorsed these attacks at rallies held in Tiananmen Square, attended by more than 10-million young people. The Chinese Communist Party closed schools and universities to enable students and pupils to engage in “class struggle”.

Most universities remained shut for six years. Entrance exams were abolished. New students were recommended by worker and peasant organisations.

Paramilitary groups of students, who called themselves Red Guards, attacked symbols of feudalism, religion and capitalism. They destroyed museums, shrines, books, paintings and Buddhist statues.

Students from Beijing Normal University travelled by train to Shadong and bludgeoned the 2 000-year-old temple of Confucius with sledgehammers, taking photographs as they did so.

The Red Guards changed the names of shops, buildings and streets, adorned them with images of Mao and shook off the “work teams” sent by the Chinese Communist Party to educational institutions to guide them. More than 4 000 of Beijing’s 6 000 odd heritage sites, and nearly all of Tibet’s 6 000 monasteries, were eventually destroyed.

The violence turned against people, “unmasking demons” and “monsters” who, without trial, were denounced as deviating from “Mao Zedong Thought”.

At Peking University, a large group attacked the head of the university and other academics. A witness, quoted in Mao’s Last Revolution by Roderick MacFarquhar and Michael Schoenhals, the primary source of this article, states: “That morning, students from all over campus were mobilised to form one boundless ocean of people’s war. The privileges of the bastards who ruled [the campus] for decades came to an end … A red terror spread across campus …”

Commenting on the incident, second-year students in the department of economics stated that “it’s like the Chairman [Mao] says: those who were beaten up got what they deserved. To obsess about the violence to the point of censuring the revolutionary masses … would be a very serious mistake indeed.”

Red Guard posters, chants, songs and slogans reduced the complexity of discourse to Twitter-like superficialities and Facebook-like verbal assaults on individuals.

Xing Lu, in her book on the rhetoric of the Cultural Revolution, argues that speech became “cultic and politicised”. As a result, interpersonal relationships were filled with mistrust and hatred, and artistic expression was replaced “with formulaic jargon and ideological clichés”.

Public denunciations, humiliations, confessions and beatings increased.

The classist violence spread throughout China and continued for a decade. Independent-minded scholars, writers and musicians were beaten and killed. Figurative artists were sent to labour camps and literary classics were burned. At least 400 000 people died. Many more were persecuted.

A number of Red Guards, now in their 60s, have recently apologised for their conduct. Song Binbin, for example, a teenager at the time, asked forgiveness for her part in the death of Bian Zhongyun, her school’s vice-principal, whose face, according to her widower, was beaten so badly it was “completely black”.

The Red Guards and Maoist academics at universities drew on Marxist-Leninism and Mao’s writings, including his recently published Little Red Book of aphorisms.

As interpretations of the texts differed widely, factions quickly developed and fell into conflict. In early 1967, alarmed at the administrative chaos in several cities, Mao ordered the People’s Liberation Army to take control of the Red Guards.

Student leaders were arrested and branded as “ultra-left counter-revolutionaries”. In 1968, Mao wrote in the People’s Daily: “The intellectual youth must go to the country, and will be educated from living in rural poverty.”

About 15-million high school pupils and university students were sent to live and work among the peasantry.

Mao had become vulnerable in the early 1960s. The economic success of Japan and other neighbouring countries threatened his communist ideology, as did Nikita Khrushchev’s denunciation of Joseph Stalin’s policies in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.

Mao, then 74, and the Gang of Four in effect hijacked the idealism of pupils and students to restore his personal and ideological dominance.

State-driven censorship had hidden from the young the enormous scale of the consequences of the Great Leap Forward, Mao’s plan to collectivise peasant agricultural production. State propaganda had also elevated him into a saviour figure. Cuban president Fidel Castro criticised the cultic status of Mao as “superstitious idolatry”.

Jasper Becker, former Guardian correspondent in Beijing, states in his Hungry Ghosts: China’s Secret Famine, that at least 10-million

critics of the policy were sent to Stalin-styled labour camps, 10-million people fled their homes in search of food, and at least 30-million people starved to death between 1958 and 1962.

Imitating Stalin, Mao’s collectivisation policy in effect nationalised land ownership and food production. Food-producing families were forced to live in communes with single kitchens, controlled by party officials. Their agricultural production was sent to state granaries and warehouses.

Mao was also influenced by Russian hostility to “Western” science, an attitude that spread to schools and universities. Scientists trained in the West were treated with suspicion, and some were dismissed.

Trofim Lysenko, Stalin’s scientific adviser, rejected genetics as an “expression of the senile decay and degradation of bourgeois culture”. A colleague called scientists who used experiments to verify results “the caste priests of jabberology”.

Becker writes that Lysenko rejected the “fascist” theory that plants and animals have inherited characteristics. In keeping with communist doctrine, he emphasised the effect of the environment on organisms. He soaked wheat seeds in icy water, claiming that this would make them adapt to being planted in winter.

Organisms are influenced by both nature and nurture. What Mao implemented from Lysenko’s simplistic pseudoscience — plant seeds much closer together to increase the yield of crops — was disastrous for Chinese food production.

Marshall Peng Dehuai, the minister of defence, was brave enough to confront Mao at the Lushan summit in mid-1959. He accused him of “sacrificing human beings on the altar of unreachable production targets”.

Mao repulsed the challenge, had Peng put under house arrest and organised a nationwide purge of party officials who did not follow “the mass line”. Peng was imprisoned, tortured and killed during the Cultural Revolution.

The Chinese Communist Party central committee stated in 1981: “The cultural revolution … was responsible for the most severe setback and the heaviest losses by the party, the state and the people since the founding of the People’s Republic. It was initiated and led by Comrade Mao Zedong.”

He and other adult politicians manipulated and duped young people. Idealists in outlook, they became fascists in action. The mould of feudalism was broken, but violence, repression and poverty continued.

On Mao’s death, the Gang of Four was prosecuted and imprisoned, many victims of the Cultural Revolution were rehabilitated and liberal reforms were introduced.

On Qingming Day (Tomb-Sweeping Day), the masses continue to venerate their family ancestors, a custom going back centuries, as in Africa.

Chris Mann is at the Institute for the Study of English at Rhodes. He writes in his private capacity.