Gaba Dlamini is one of over 300 doctors in Gauteng who received special training to treat men who have sex with men.

The reception area of Gaba Dlamini’s office is furnished with a row of plastic chairs lined up in front of an old couch. A big round yellow poster is balanced against the wall.

The white italic letters on the poster read: “Psst. Hey you. You’re probably wondering what this yellow dot is trying to tell you. Why is it so big? Why is it so yellow? Why did it just say ‘Psst’?”

Dlamini is a medical doctor with a private practice in Zondi, Soweto.

The poster goes on: “Well, it’s probably because this yellow dot, and all the others like it, are symbols. Symbols that you’re in a safe, non-judgy space. Here, you can talk to your yellow dot doctor about anything. Yes, even THAT thing. Seriously try them. They’re unfreakoutable.”

Dlamini is one of 350 general practitioners in Gauteng who have been trained to provide healthcare services for men who have sex with men. These are not only gay men. They’re often married to women, but have sex with men outside their heterosexual relationships.

Studies have shown that men who have sex with men are particularly vulnerable to HIV infection, and so are their sexual partners.

“Yellow dot doctors have seen and heard it all, and they always have your best interest at heart,” the poster continues. “So when you see the yellow dot, feel free to open up. Because the more open you are, the better we can treat you.”

Strange request

Dlamini thought he had seen it all. But last year he received a phone call from the Anova Health Institute with what he, at the time, considered a rather strange request: the organisation wanted him to be part of a yellow dot pilot project.

Yellow dot doctors are private physicians who have received training from Anova to provide healthcare services that accommodate the specific needs of men who have sex with men.

“Men who have sex with men is a medically accepted term that describes a sexual behaviour and does not take into account culture or identity,” says Kevin Rebe, a specialist HIV clinician at Anova. “This population includes men who identify as gay, as well as men who identify as heterosexual or straight but might also be having sex with men.”

According to the World Health Organisation, men who have sex with men form part of key populations who are at an increased risk of HIV. The organisation estimates that men who have sex with men are 13 times more likely to be infected with HIV than the general population.

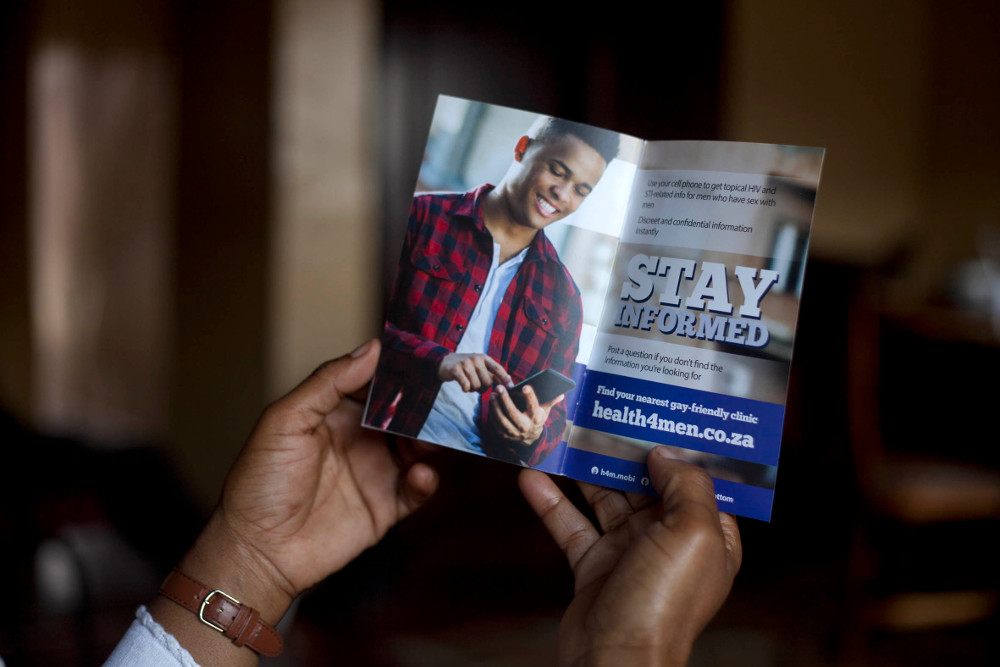

Men who have sex with men are often discriminated against at health facilities. (Oupa Nkosi, M&G)

Men who have sex with men are often discriminated against at health facilities. (Oupa Nkosi, M&G)

The biggest risk factor for HIV infection and transmission in men who have sex with men is biological, says Rebe.

“HIV is transmitted much easier through anal sex than vaginal sex. A man having anal sex without protection has a 16 to 20 times higher risk of being infected with HIV than a man who’s having vaginal sex without protection,” he says.

“This is because vaginal tissue is modified for sex, it’s thicker and contains mucus cells so it self-lubricates the lining during sex. Whereas the lining of the anus doesn’t self-lubricate and is much thinner, so it’s more liable to tear during sex. If there’s exposure to semen containing HIV, a tear can be an entry point for HIV to take hold.”

High HIV prevalence

The South African Marang Men’s Project, a 2014 survey conducted by the Human Sciences Research Council, found high HIV prevalence rates among men who have sex with men in South Africa’s three largest cities. In Cape Town, 22% of the men who participated in the study had HIV, 26% in Johannesburg and 48% in Durban. According to the South African National Aids Council, 12.2% of the general population is living with HIV.

But despite this risk, societal factors such as stigma still hinder men who have sex with men from using HIV prevention and treatment services.

Rebe explains: “Men who have sex with men have been discriminated against in society and by healthcare systems for a very long time. These negative experiences of the health system act as a barrier. If a man who has sex with men seeks medical care for a sexually transmitted infection and is told by the healthcare worker that they shouldn’t be having anal sex, that man is not going to come back.”

He says access to healthcare among men who have sex with men is lower than in men who have sex with women only, and this can result in sexually transmitted infections not being diagnosed and left untreated.

“If people are reluctant to attend a healthcare facility they are less likely to get tested, to know their status and to get treatment if they’re positive or pre-exposure prophylaxis if they’re negative,” says Rebe. “Having healthcare systems that are perceived to be unfriendly spaces promotes HIV, because it means diagnoses are not made and people are not accessing treatment.”

Many men not seeking care

Dlamini was shocked to learn about the extent of the discrimination men who have sex with men faced when consulting doctors.

“I knew people had different sexual preferences, but I didn’t know the frustrations and problems that this community faces,” he says. “It makes me sad that there are doctors who are not nice to patients. We need to do the best we can for all patients, no matter what their sexual orientation.”

Now that he is aware of the problem, Dlamini says he tries his best to make sure all of his patients feel welcome in his office and are comfortable to disclose any information to him.

“I don’t want to have a patient coming to me and leaving without getting the service they needed because they were afraid of being judged,” he says.

Once a doctor agrees to be part of the campaign and completes the training, his practice is branded with yellow dot posters similar to the one in Dlamini’s office. These doctors are added to a database on Anova’s website so that patients know where to find them.

Rebe says providing targeted care for men who have sex with men will also benefit wider society. “If we implement the correct screening for sexually transmitted infections as well prevention packages, we can lower the rate of HIV within this concentrated population.”

According to a 2011 study published in the journal Aids and Behaviour, more than 60% of the men who have sex with men surveyed in Soweto reported regular sexual partnerships with women.

Gaba Dlamini is a yellow dot doctor and provides friendly healthcare services to men who have sex with men

Gaba Dlamini is a yellow dot doctor and provides friendly healthcare services to men who have sex with men

“Men who have sex with men are a bridging population and if we can decrease the rate of HIV and sexually transmitted infections in this focused group, we can decrease the rate of transfer back into general society,” Rebe says.

A 2011 World Bank study found that HIV prevention and treatment services aimed at men who have sex with men in low- and middle-income countries had a positive effect on overall HIV epidemic control.

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and Aids set the 90-90-90 goals in 2014. These are targets that countries have to reach by 2020 to stop the epidemic by the year 2030. The goals are to diagnose 90% of people living with HIV, to provide treatment to 90% of those diagnosed with HIV and for 90% of people on treatment to achieve viral suppression, when the viral load is not detectable.

But Rebe says this target cannot be reached without addressing the healthcare needs of vulnerable groups such as men who have sex with men.

“The best results are obtained if you focus on the key populations [at an increased risk of HIV] specifically as well as on the general population. If you ignore the key populations and only focus prevention and treatment efforts on general society, you will not reach the expected reduction in new HIV infections.”

Good quality care for everyone

On the other side of Johannesburg, in Morningside, Sandton, Neville Paulsen waves goodbye to a patient: a little boy in a blue school uniform and thick-framed glasses.

Like Dlamini, Paulsen is a yellow dot doctor.

“We see all types of patients at this practice,” Paulsen says and takes a seat behind his desk.

“But some of our patients who have issues relating to sexual health are not always comfortable to talk about it, so the yellow dot lets them know that this is a safe space.”

Paulsen says the yellow dots will help address the barriers men who have sex with men face when trying to access healthcare, by normalising their healthcare experience and treating them in the same facilities as other populations.

“We’re not placing a yellow dot on the patient, it purely means that they can feel comfortable to talk to us about sensitive things,” he says. “The yellow dot should tell the patient that this doctor will not freak out.”