Regular droughts in South Africa mean the country does not have enough water for its needs for two to three years per 10- to 20-year cycle.

Richards Bay is joining other coastal cities and building a desalination plant to survive the crippling drought. By converting sea water into fresh, the plant will allow the town to tap into what engineers refer to as an “almost infinite” water resource.

But water and sanitation officials say the option is one of “last resort” and has come about because of slow work by the water department on other projects.

The water department’s own plans show that desalination was seen as a last resort – becaue it is so expensive and uses so much electricity. Research by the Water Research Commission breaks this down: the City of Cape Town can produce water for R1.25 a kilolitre using a mix of water sources, while Rand Water in Gauteng can produce water for R2.50 per kilolitre. But a large desalination plant along the coast produces water at anywhere between R5.80 and R8.30 per kilolitre.

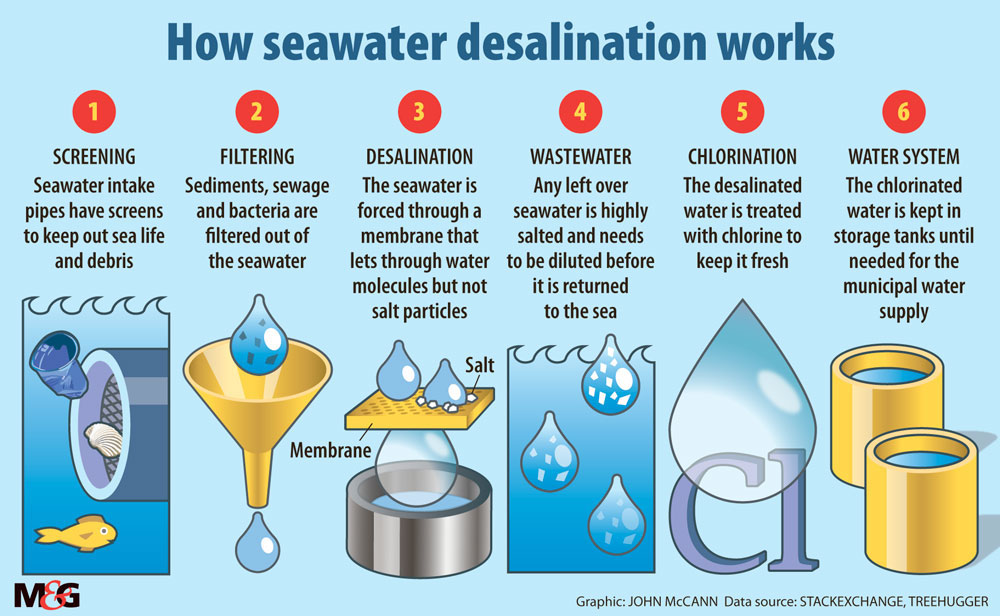

Big plants, such as the one being built in Lamberts Bay in the Western Cape, use huge amounts of electricity to remove salt from seawater so that it can be drunk safely. A conventional water treatment plant uses 0.3 kilowatt-hours of electricity to treat a cubic metre of water, while a desalination plant uses up to eight kilowatt-hours of electricity.

In its desalination strategy, the water department notes that while the process “could provide an unlimited resource of freshwater”, it would only be considered after all other options. This is because of the escalating cost of electricity and the lack of a local desalination-plant industry and expertise.

An official in the department, who is involved in water planning but is not authorised to speak to the media, said that this was why desalination was at the back of the queue. “We need to wait for the technology to mature so we don’t have to pay the R&D [research and development] costs and run plants that suck up critical electricity. But we should have had that breathing space.”

Other options would include, for instance, treating sewage water back to drinking water, a much cheaper process in terms of electricity and cost. An attempt to do this in Durban was rejected by the local community, which refused to drink the water on religious grounds. There is also the option of fixing old water infrastructure in municipalities, where up to a quarter of the water is lost through leaks.

But the decision to desalinate seems to be the result of delays to other infrastructure projects. An official at the Trans-Caledon Tunnel Authority says desalination “was always going to be the technology of choice, in the future”. The statement is based on documents such as government’s 2012 National Water Resource Strategy. This master plan looked at how much water each town and city needed, and how much the water department could supply up to 2035.

For most cities, water use was projected to outstrip supply before that date. In Johannesburg and Cape Town, that crunch would come before the end of this decade. For Durban and areas such as Richards Bay, people and industry were already using more water than was available by 2005.

Solving that problem has been the job of the water department, through agencies such as the Tunnel Authority. Mega-projects, such as the second phase of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project, fall under its purview. This critical scheme is half a decade behind schedule.

Regular droughts in South Africa mean the country does not have enough water for its needs for two to three years per 10- to 20-year cycle. Historically, big dams have been built to store water for the dry years. But the Tunnel Authority official says this breathing space has been whittled away by delays: “The delays in all sorts of bulk water schemes means we need to turn to emergency options like desalination.”

Although there are 4 400 registered dams across South Africa, the country’s water security relies on fewer than 50. Upgrades to these dams, such as that planned for the Tzaneen Dam in Limpopo, have been delayed by years or indefinitely postponed. Upgrades to Hazelmere Dam, which supplies Durban and the North Coast, were delayed by six months last year. De Hoop Dam – opened by the president with much fanfare three years ago – has been similarly delayed by half a decade.

These infrastructure delays mean that when a drought hits, there is not enough water stored to get communities such as Richards Bay through the dry times. Mhlathuze Water, which supplies the area, implemented rolling restrictions last year. Similar restrictions in the 2009 drought saw emergency desalination plants built in Mossel Bay, Sedgefield and Plettenberg Bay. The Hillcrest aluminium smelter in Richards Bay opened its own plant last year, at a cost of R74-million.

For Richards Bay, plans for a packaged desalination plant were gazetted earlier this month. The notice said that this was “to mitigate the impact of periodic shortage of water”. The small scale of the plant, and its lifetime of less than five years, means it will use up to 75% less electricity than larger plants. But there is no information on what the actual cost will be. Speaking in the province last year, the water department’s former director general, Margaret-Ann Diedricks, said: “It’s time to stop talking about expense. Now we need to talk about implementation.”

Nevertheless, the expense is expected to be high, because the technology is still developing. If other water supply projects had been done on time, South Africa might have been able to avoid the cost for now.

The water affairs department had not responded to requests for comment by the time of publication.