When it comes to good health, sugary drinks are bad news.

Your sweetened soft drink is going to cost you more after Finance Minister Pravin Gordhan’s budget speech.

But if you are a sucker for a can of soda, you may be pleased to know that it is going to cost you roughly 50c more, as opposed to the almost R1 extra initially intended.

In his announcement Gordhan reaffirmed government’s plans to go ahead with a tax on sugary beverages. But treasury has refined the proposed tax, offering some concessions after public hearings and discussions with affected industries.

Health advocates have welcomed the continued commitment to the tax, but argued that the refinements may not generate as extensive a set of health benefits as initially hoped for.

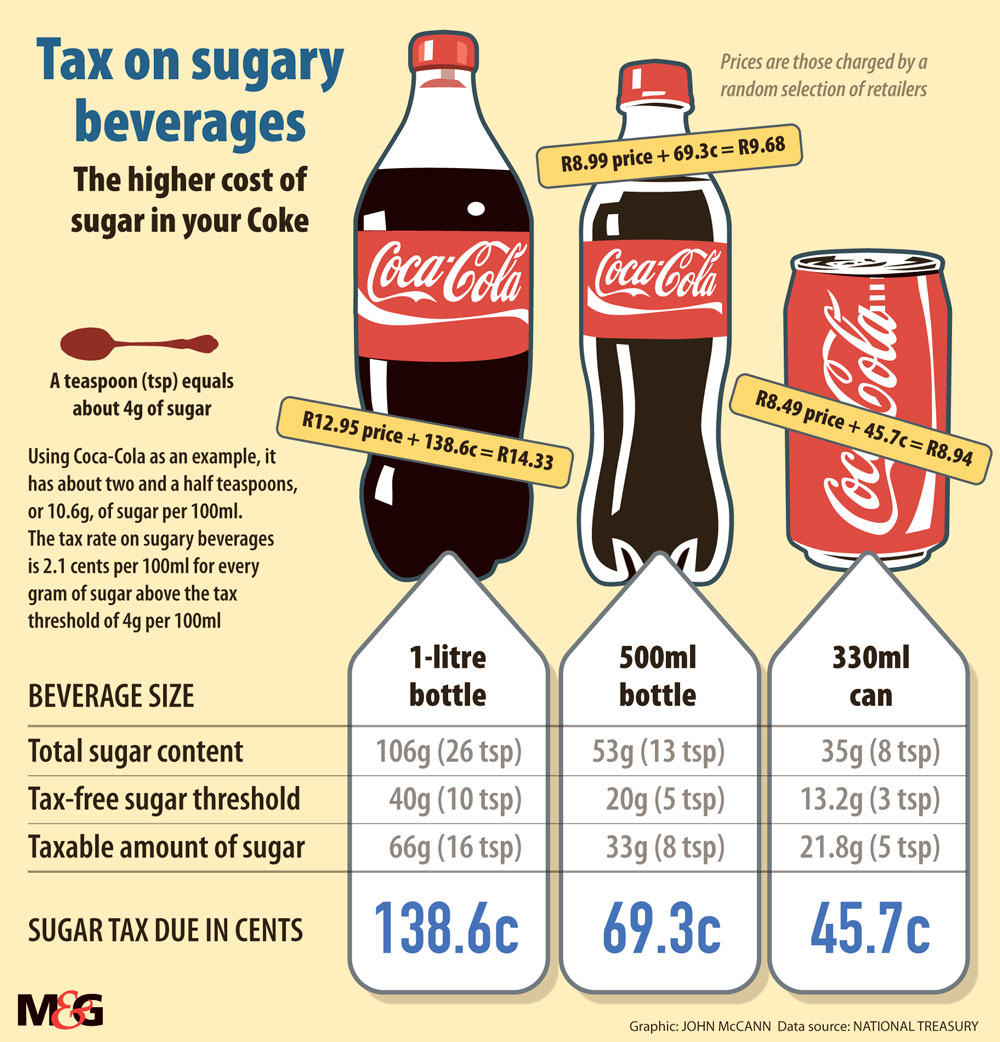

The design of the tax has been revised, the treasury said, with the tax rate now set at 2.1c a gram of sugar content, down from 2.29c/g under the first iteration of the proposal. Importantly, a new threshold has been included, and the tax will only apply to sugar content in excess of 4g/100ml in each drink. This means a 330ml can of Coca-Cola, containing just over eight teaspoons of sugar, will cost an extra 46c.

Aviva Tugendhaft, deputy director of the health advisory programme Priceless SA, said the initial proposal amounted to a 20% tax on sugary drinks but the revised proposal takes the rate closer to 10%. “We are happy that the tax is still going ahead and we believe a tax at that rate will still have an impact.”

She said a 20% tax could have had a greater health benefit.

According to Priceless SA’s presentation to Parliament, a 20% tax would prevent a quarter of a million people from becoming obese. Priceless SA (Priority Cost Effective Lessons for System Strengthening South Africa) is made up of Wits University School of Public Health, the Medical Research Council and the Wits Unit in Rural Public Health and Health Transitions Research (at Agincourt in Mpumalanga).

Although the tax will raise revenue — how much remains to be seen — for the taxman, it is designed as a measure to curb wider costs to South Africa’s healthcare system.

Obesity is linked to the rising epidemic of noncommunicable diseases such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The healthcare spend on diabetes was estimated at between R11-billion and R20.5-billion in 2010.

The treasury also said in the budget review that a broader World Health Organisation (WHO) definition will be applied to cover intrinsic and added sugars in sugary beverages.

This, according to treasury officials, means any sugars, including naturally occurring sugars such as those derived from fruit or fruit juice concentrates added to sweeten drinks, will be also be taxed.

Milk and 100% fruit juices have been exempted from the tax for the time being, in line with other countries that have applied a similar levy.

But the treasury has said the inclusion of 100% fruit juices “will be considered in future” because many health experts have argued these juices have the same or very similar health consequences as those of sugar added to soft drinks.

The announcements on the tax coincide with new reports that a 10% tax in Mexico has driven sustained decreases in the sale of sugary beverages after it was implemented in 2014. Taxed beverage sales in that country declined by 5.5% in 2014, and 9.7% in 2015, or an average of 7.6% over the period, according to research published by health policy journal Health Af fairs. Sales of untaxed drinks increased on average 2.1% over the same period.

Under the budget’s revised proposal half of the proposed tax rate will apply to concentrated beverages.

Although the treasury will not ring-fence the funds generated by the tax, more funding will be made available in the budget to the national department of health to spend on intervention programmes for noncommunicable diseases.

During public hearings, industry and unions raised concerns that the tax would reduce jobs in the sugar and beverage industries.

But an analysis by treasury of the initially proposed 20% tax shows a maximum of 5 000 jobs may have been affected.

This was based on the assumption that industry did not adapt to the tax by, for example, reformulating drinks to contain less sugar. Assuming that businesses did change their products, treasury said the potential decline in sales volumes and job loss “will reduce significantly, if not entirely”.

The revised tax and inclusion of the new threshold has reduced the effective tax rate and should reduce the effect on jobs, even in the face of no reformulation of drinks, according to the treasury.

The tax will be introduced later in the year in line with legislative processes in Parliament.

This additional time for consultation on the tax was welcomed by the drinks industry.

Mapule Ncanywa, the executive director for industry body BevSA, said the organisation remained committed to discussions to identify the most effective solution to the problem of obesity. As an alternative to the tax BevSA has proposed reformulating products to include lower- to zero-sugar variants and a consumer awareness drive.