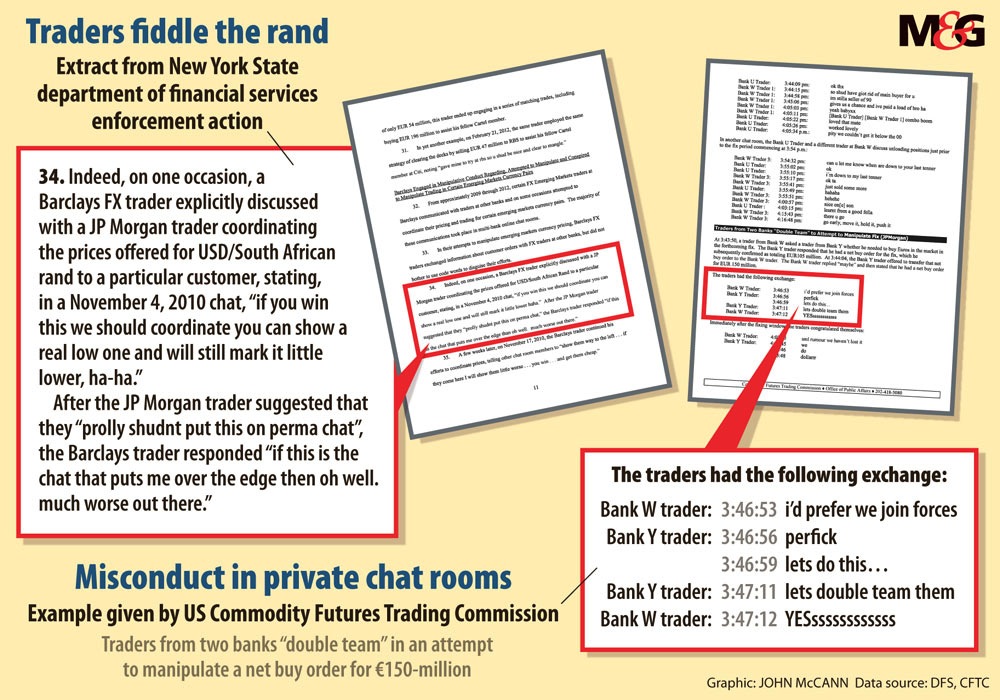

In a chat room in 2010, a Barclays foreign exchange trader explicitly discussed with a JP Morgan trader co-ordinating the prices offered for dollars/rands to a particular customer.

“If you won this, we should co-ordinate … you can show a real low one and will still mark it a little lower, ha-ha.” After the JP Morgan trader suggested they “prolly shudnt put this on perma chat”, the Barclays trader responded, “if this is the chat that puts me over the edge, than oh well. much worse out there”.

The traders often did not bother to use code words to disguise their efforts when it came to emerging-market currencies, unlike when they attempted to fix the trades of major currencies.

The date of the chat – the details of which are contained in the New York State department of financial services plea bargain with Barclays – suggests that the Barclays trader in question was Jason Katz, one of 32 traders named in the Competition Commission’s case against 17 banks for the rigging of dollar/rand currency trades. Katz was also implicated in noncompetitive behaviour while he was an employee at Standard Bank New York and BNP Paribas.

In January this year, he was the first trader to admit criminal misconduct when he entered into a plea bargain with the United States department of justice.

In mid-February this year, the Competition Commission referred a case of collusion to the Competition Tribunal for the prosecution of Standard Bank, Absa, Barclays Bank and Investec locally. It is also seeking action against international banks, which include the Bank of America, Merrill Lynch International, BNP Paribas, JP Morgan Chase & Co, HSBC, Standard Chartered Bank and Credit Suisse.

The commission said it found that, from at least 2007, the respondents had a general agreement to collude and manipulate prices in relation to trade involving the dollar and the rand. As with other rate-rigging cases, the traders often organised their activities in online chat rooms.

The commission is asking the tribunal to impose an administrative penalty of 10% of turnover. Absa and Barclays Africa have received immunity in exchange for their co-operation. Citibank settled with the commission within days of the referral being lodged with the tribunal for a reduced sum of almost R70-million in exchange for its co-operation.

Sipho Ngwema, the spokesperson for the commission, said the settlement was based on 10% of annual turnover – the maximum penalty prescribed by the Act – and the discount negotiated between the parties, adding it was not an indication of what the other settlements might be.

The financial sector seemed to be taken by surprise by the case, but it had been a long time in coming. The commission first announced on May??19 2015 that it would look into allegations of price-rigging when it came to trading the rand. The announcement was made on the same day that the consent order (or plea bargain) was issued by the New York State department of financial services.

Investigations conducted in the United Kingdom and the US and found widespread noncompetitive behaviour in the forex trading centres of the world – New York and London. In some cases, as the consent order with Barclays shows, other currencies such as the rand were found to be implicated.

The Brazilian real was one in which traders simply agreed to boycott local brokers to drive competition down. In December, the Brazilian government settled with five foreign banks on a figure of about $54-million banks for their role in the manipulation of the currency. The banks were Barclays, Citigroup, Deutsche Bank, HSBC Holdings and JP Morgan Chase & Co.

The cases show that similar tactics were employed by traders to manipulate rates.

In its consent agreement with Barclays, the New York State department of financial services laid out a great deal of detail about how, from about 2008 to 2012, some Barclays traders communicated with those at other banks to co-ordinate attempts to manipulate prices of some currency pairs and the benchmark rates, including the WM/Reuters and euro foreign exchange reference fix rates.

The majority of these communications took place in multi-bank online chat rooms where, in their attempts to manipulate these benchmarks, the traders exchanged information about the size and direction of their orders, as well as co-ordinated trading, and discussed the spread between the bids and offers the banks were presenting to customers.

The traders used code words when communicating in multi-bank chat rooms to conceal some aspects of their communications and to avoid detection. One particular chat room, referred to by participating and other traders as the “Cartel”, included traders from Citigroup, JP Morgan, UBS, RBS and Barclays, which specialised in trading the euro. Membership of this exclusive chat room was limited to invited traders.

“By sharing information through multi-bank chats and colluding in their trading, these already influential traders dramatically amplify their ability to manipulate prices”, the department said in the documents.

As one Barclays trader stated on a multi-bank chat, “we are 3 of the top 4 eur books on the planet … if we cant help each other with liquidity … who can?”

When one Barclays forex trader became the main euro trader for the bank in 2011, he was desperate to be invited to join the Cartel because of the trading advantages. After extensive discussions about whether he would “add value” to the Cartel, he was invited to join for a one-month trial, but he was warned, “mess this up and sleep with one eye open at night”.

The incentive structure for traders, according to the department’s consent order, “creates a risk that a trader will deliberately engage in trading behaviour to manipulate the fix rate in order to increase his or her profits by buying or selling large orders, or simply by making bids or offers for large amounts with the intent to move prices rather than engage in actual transactions. These profits could be increased even further if the trader co-ordinated his or her trading activity with FX traders at other banks.”

It would also prove to be lucrative for the banks.

Profiteering banks slow to act

In May 2012, Barclays held workshops at which traders discussed their efforts to co-ordinate foreign exchange fixes.

During and following these workshops, traders asked for guidance from the compliance and legal divisions of the bank about proper communications in the multi-bank chat rooms, but didn’t receive it until October and December 2012.

Around the same time, Barclays reached a global settlement relating to the manipulation of key benchmark rates, most notably the London interbank offered rate (Libor).

Despite learning about forex traders sharing information in the interbank chat rooms at least as early as May 2012, Barclays did not shut them down until October 2012, and it did not begin a full investigation of forex trading misconduct until the publication of a Bloomberg article in June 2013.

The New York department of financial services fined Barclays $485-million. But other fines – $400-million by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, $342-million to the Federal Reserve, $650-million by the US department of justice and £284-million by the United Kingdom’s Financial Conduct Authority – saw Barclays fined about $2.4-billion in total.