A conveyor belt will transport coal from the mines to Eskom's Medupi power station in Limpopo.

Wildfires, spontaneous combustion of coal, floods, drought, angry people … welcome to the future that coal-fired power stations will have to deal with in a warming South Africa.

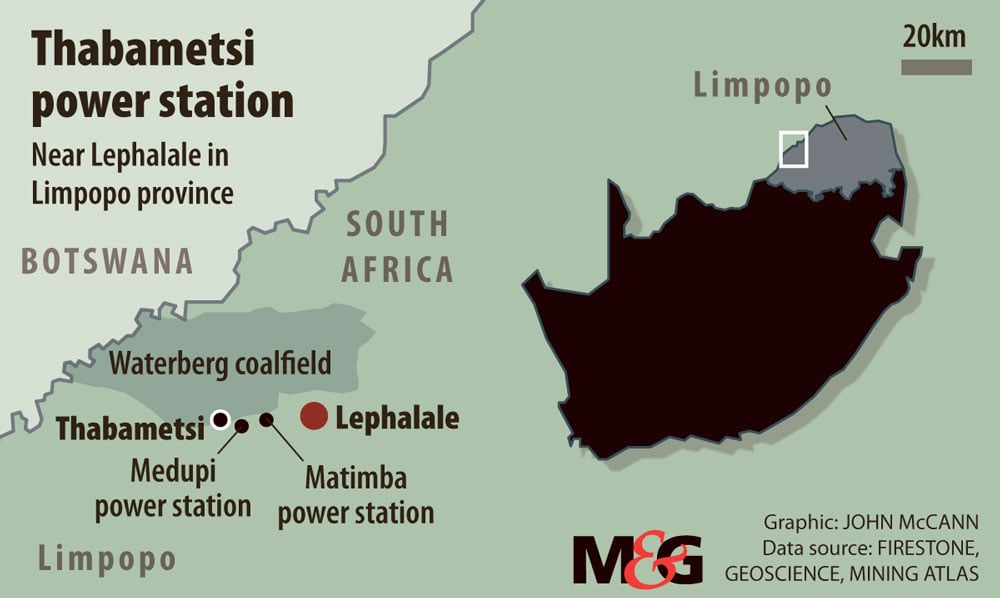

These alarming possibilities are mapped out in a climate change resilience assessment done for the proposed 1 200MW Thabametsi power station in Lephalale, western Limpopo.

Earthlife Africa Johannesburg has challenged in court the decision to grant the station environmental permission to go ahead, with judgment now reserved.

A critical aspect of the legal challenge is that environmental authorisation should have, but did not, require an assessment of the effect the plant would have on climate change. Instead, the opposite was done: an assessment on how climate change over the years could affect the plant.

But that assessment is revealing in itself of the risks of combining the construction of a massive coal power station with rapidly rising temperatures.

At a basic level, the assessment looks at how the climate in Lephalale will have changed by the 2050s and how that will affect the plant. It is an already dry and hot part of the country; rainfall is less than the national average and average temperatures for January and February hover near 30°C. The record high is 43.6°C.

Water is so scarce that a R10-billion transfer scheme is under construction to bring water from western Gauteng to the Mokolo Dam, which supplies Lephalale. This scheme is mainly to supply the Medupi power station run by Eskom and the Grootegeluk coal mine, which supplies Medupi.

When the transfer scheme is complete, in 2019, Lephalale will have just enough water for everyone.

But the assessment paints a much more difficult future beyond 2019. It identifies 12 specific risks that the Thabametsi power plant will face by the 2050s.

At the low end, these include heatwaves, wildfires and an increased danger of spontaneous combustion of coal stockpiles. At the other weather extreme, heavy downpours and flooding will wet stockpiles and damage equipment.

These problems can all be worked around; raised machinery and flood defences will help when the Mokolo River bursts its banks and quick response plans and procedures will lower the threat of fire.

But it is the high-level risks that are a real problem for Thabametsi. The climate assessment says these include increased temperatures reducing the thermal efficiency of coal, so less energy is produced per tonne burnt, resulting in a more expensive plant; poor water quality at the plant as a result of polluting industries and agriculture upriver; less water flowing because of upstream use and drought; and a “loss of social licence to operate as communities suffer from water shortages”.

The last point could lead to social unrest and threaten the plant’s operations, according to the resilience report.

The water supply will be the greatest headache. Lephalale does not have enough water. The Mokolo Dam is rated by the water and sanitation department as “high risk” because supply only just meets demand.

This is without allocation for ecological flows, a legal requirement where each river must have enough water running through it to keep downstream ecosystems going. The augmentation scheme to bring water from Gauteng was designed to supply less industry than is being planned around Lephalale.

The climate change assessment says government water plans for Lephalale “do not factor in climate change impacts” and there is “some uncertainty” about how much water the Thabametsi plant will be allowed to use.

The assessment used climate projections from the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, the United Nations’ climate body and the University of Cape Town’s Climate Systems Analysis Group.

Climate change will affect the Thabametsi power station and it will affect climate change — hence Earthlife Africa’s case.

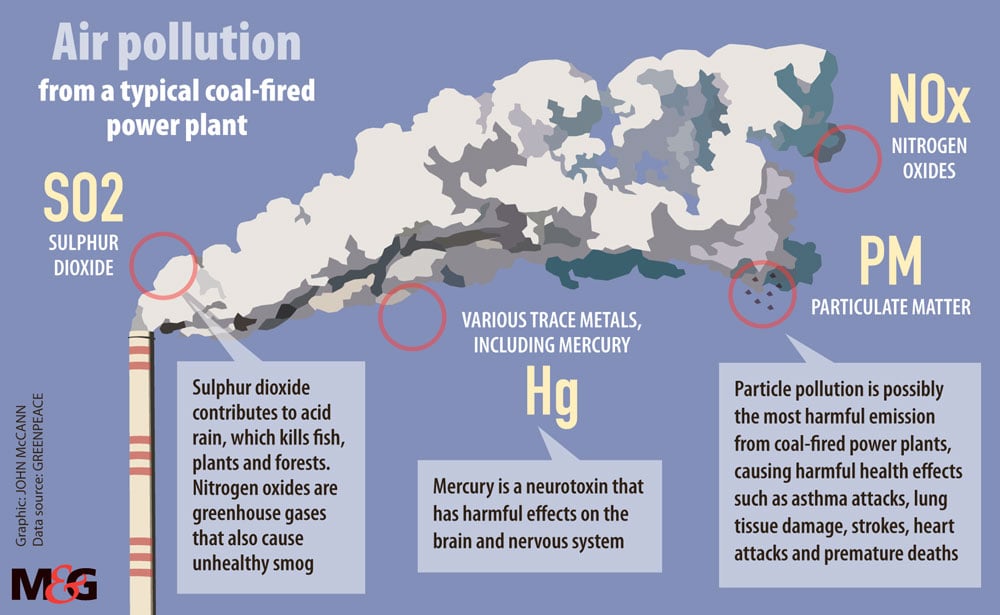

Impact assessment reports for similar power stations have not historically looked at the impact they would have on making the world warmer as a result of the gases coming out of their smokestacks.

Down the road from Thabametsi, the Eskom plant at Medupi was built despite its annual emissions of 25-million tonnes of carbon dioxide. This is more than 115 other countries emit individually and is about 5% of South Africa’s emissions.

By the time it is operating in the early 2020s, Thabametsi will contribute 2% of the country’s carbon emissions. This will double to 4% by 2050, as other plants are shut down and South Africa reduces its overall emissions.

The plant will contribute a large chunk of the country’s emissions at a time when the impact of these emissions will leave it struggling to operate.