Traders speak openly about the illegal trade in rough diamonds through border towns of Gbitti

Diamond industry experts have been talking about “peak diamonds” for decades. But, unless there is a major reserve discovery, the end of the diamond era could well be upon us, because demand is predicted to outstrip supply from 2019 onwards.

“The basic story, as I understand it, is that consumption of diamond products has been pretty consistent and growing. But the exploration successes haven’t transpired,” said Craig Smith, executive manager at the Geological Society of South Africa. “There is concern among the geological community that there will not be enough to supply demand in the long term.”

Bain & Company, which releases an annual diamond report in collaboration with the Antwerp World Diamond Centre, expects demand for diamonds to be greater than supply from 2019 onwards.

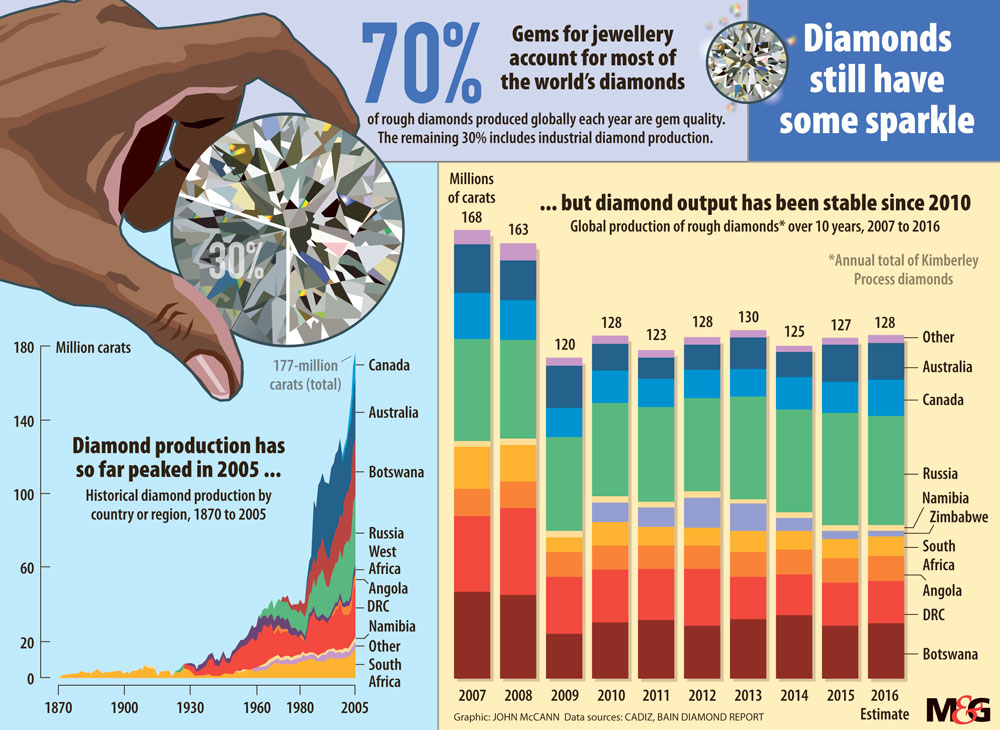

Peter Major, the director of mining at Cadiz Corporate Solutions, said world diamond production had so far peaked at 177-million carats in 2006. Current annual production is about 140-million carats, said Major, adding that global supply of rough diamonds is expected to expand at a compound annual growth rate of 1% between 2016 and 2021.

“We all have this belief we have seen peak production [and], unless we see the discovery of another major deposit, producing something like a million carats a month, the steady tailing off of supply will continue,” said John Bristow, an independent consultant. “Consequently, there has been the underlying view that diamonds are finite, there is a shortage in supply, increase in demand from places like China, and hence prices will go through the roof.”

Smith said the last discovery of a very large mine was De Beers’ Venetia Diamond Mine in Limpopo, which came on stream in 1992. All new mines subsequent to that have been smaller. Existing mines will begin to phase out, with the largest reserves in Botswana expected to be depleted in 30 to 50 years.

Bristow said there has not been a major world-class discovery since 1991, when Canadian deposits were found. “Though the Marange production in Zimbabwe provided significant new production to the market for a short period, this deposit is effectively exhausted. Other new mine developments such as Liqhobong in Lesotho and Gahcho Kué and Renard in Canada are small — hence the long-term supply trend is moving downwards,” he said.

Diamonds occur from two major sources. The most important source is kimberlite — a volcanic rock named after the diamond-mining town of Kimberly that occurs in vertical, champagne-glass or funnel-shaped structures, known as pipes. The second major source are alluvial diamonds, which are formed through the erosion of the kimberlite pipes, resulting in the release of diamonds into rivers.

“There are 6 000 or 7 000 kimberlite pipes that we know of around the globe. Of those, only about 10% carry any diamonds at all and, of those, only about 50 or 60 have ever been mined economically,” said Smith.

A kimberlite pipe can be economically mined if the cost of discovery, extraction, taxation and getting the diamonds to market does not exceed the revenue earned. But economics change all the time, said Smith.

“Peak oil has been predicted many times over the last few decades and we are still not there. It turns out there were major unpredicted developments in both supply and demand in the fossil fuel business,” he said. “If the diamond price doubled overnight you could probably do more with currently known resources.”

Major said peak production of almost anything is limited only by demand. Peaks are not based on resources running out; they are based on the commodity price.

“We’ve heard of peak oil and diamond and gold and other production for decades. But as soon as prices go up, production increases — as if by magic — and we hit a new peak,” he said.

Real diamond prices are also much lower now than they were at their last peak. “And if they go up, I will bet that production will rise too,” Major said. “So maybe we never hit 177-million carats again. And maybe we do … What does it matter? It’s all related to prices and demand in my view.”

Bristow said: “The idea that diamonds are going to get scarce or see a ‘peak’ scenario and go away is debatable. Quality gemstone diamonds larger than two carats have always been scarce and the key drivers of pricing of these goods will be demand driven.”

He said the diamond business and its product and pricing are highly elastic, with a great range of sizes, qualities, colours and prices. Finished gemstone product varies from very small single pointers, which sell for a few dollars a carat, to exceptionally rare white and coloured flawless stones such as the Aygle pinks, which sell for a $1-million and more a carat.

Small and mid-range diamonds are also subject to commodity price cycles. “What ordinary middle-class and wealthier people choose to

buy is based primarily on their income and disposable income. Diamonds are a luxury product and so when things are tough out there, people pull on the reins,” said Bristow.

At the bottom end of a commodities cycle companies also cut down exploration budgets — if not cutting them out entirely.

“There has been very little exploration for quite some years. Green- fields exploration for diamonds requires large balance sheets. And no one, including De Beers, Alrosa and Rio Tinto, is currently spending lots of money pursuing diamond discoveries. There are lots of still prospective parts of the world with difficult terrain, and sand and vegetation cover,” he said.

Smith said new discoveries will probably require finding kimberlite pipes under thick geological cover. Some kimberlite pipes in Botswana, for example, are as old as 240-million years, but are mostly covered by varying thicknesses of much younger Kalahari sedimentary rocks and therefore not exposed at the surface.

“To ‘see’ beneath this cover requires a combination of good geological understanding and the latest geophysical technology — not to mention the willingness to spend large sums of money in the search,” said Smith. “Since the 1960s geologists and geophysicists have discovered a lot of kimberlites in Botswana, but more can be expected with improved techniques.”

Said Bristow: “I still believe there are a few ‘elephants’ lurking out there … The diamond business has been around for about 4 000 years and it won’t be going away anytime soon.”

New sources: Synthetic, Granny’s and tailings

For industrial purposes, the prospect of diamonds no longer being mined — having passed peak production— is far less daunting than peak oil.

“Industrial use of natural diamonds is largely a thing of the past, said Craig Smith, of the Geological Society of South Africa. “Natural diamonds were once used in drill bits and cutting tools, but these days this market is filled by synthetic diamonds produced through a manufacturing process.”

But in the jewellery market, natural diamonds remain king and demand remains robust despite the normal ups and downs of market cycles, he said.

But independent consult John Bristow sees the diverging trend of decreasing supply and increasing demand, which has been put forward as a rationale for a long-term price driver by producers and diamond analysts, as misleading.

Synthetic gems or “grown” diamonds are increasingly contributing to the small or “cheap” end of the diamond market. “Why mine and recover that stuff when you can grow it very easily?” he said.

World production of synthetic diamonds is enormous. The technology and ability to grow synthetic gems has progressed rapidly, and so the natural gemstone market is seeing the increasing appearance of synthetic gems into the lower end of the market.

“Swarovski is releasing its own range of lab-created diamonds. And stars like Leonardo DiCaprio are backing a start-up called the Diamond Foundry, which is taking aim at the diamond mining industry and seeking to grow its own ‘real diamonds’ in labs in just a matter of weeks,” said Bristow. “Other companies are doing the same, particularly in China and Singapore.”

The growth of cheaper synthetic or grown gems at the bottom end of the market will, ironically, allow a greater number of “new diamond owners” into the market — and have a positive rather than negative effect on the industry as a whole, said Bristow.

A further important part of the diamond supply-demand equation is that, since the global financial crash of 2008/2009, the recycling of “Granny’s diamonds” has had a notable effect on the diamond market. Some market observers are predicting that in the next five to 10 years recycled diamonds will constitute about 15% or more of the supply of the gemstone business.

Added to the growing contribution from synthetic gems and recycling, countries such as South Africa and Botswana have millions of tonnes of old tailings material containing diamonds in large and small mines. In the future the reprocessing of these tailings with new technology will also contribute to world diamond supply.