Less is more: Malusi Gigaba has distanced himself from Chris Malikane’s comments

This week, the government tweeted rather proudly that the rand had strengthened to R12.80 to the dollar, intimating that the positive move was a result of new Finance Minister Malusi Gigaba’s “hard work increasing investor confidence”.

But economists and investment analysts say the stronger rand had nothing to do with South Africa or the finance minister’s road show.

Instead, a confluence of global factors is helping to support the currency and bonds, along with those of other emerging markets. Not least of these is the global hunt for yield — the drive by global investors to direct money towards assets that deliver better returns than many developed markets, where interest rates remain low as a result of ongoing easy monetary policy.

In the wake of a Cabinet reshuffle, two credit ratings downgrades and the likelihood of a third, the relative improvements in the performance of the rand and government bonds have been described as “counterintuitive”.

“But it is really a global, sentiment-driven story,” said Isaah Mhlanga, an economist at Rand Merchant Bank, and it has benefited emerging markets where economic fundamentals have picked up.

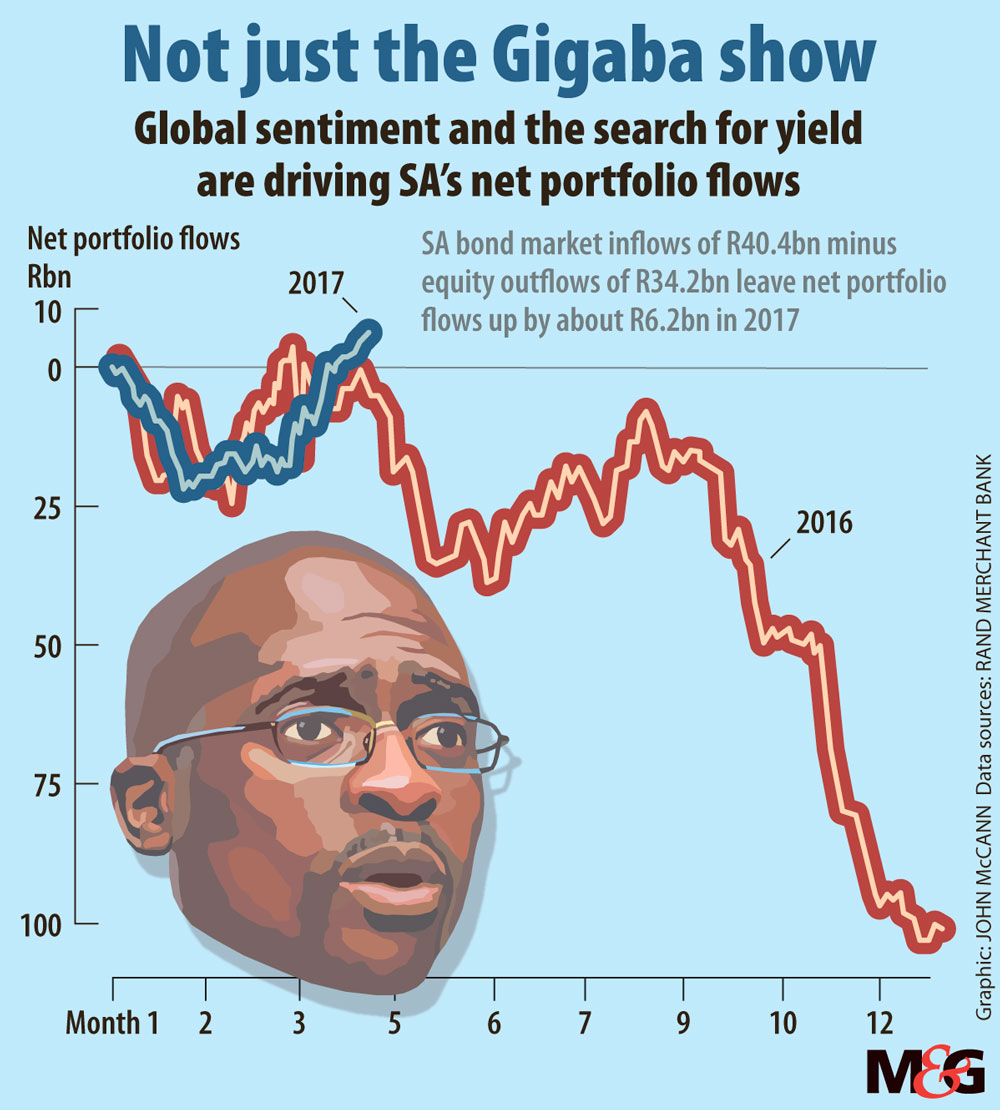

In South Africa’s case, the local bond market has seen R40.4‑billion in inflows in the year to date, he said. At the same time, equities have seen outflows of R34.2‑billion. So, on a net basis, portfolio flows stand at about R6.2‑billion. This is compared with the same period last year, which saw net outflows of R3‑billion.

Political dynamics — particularly in the United States, and what they mean for proposed rate hikes by the Federal Reserve (the Fed) — have played a key role in market sentiment.

As part of his election campaign, US President Donald Trump promised to push through steep tax cuts and investment in infrastructure, contributing to expectations of job creation, economic growth and, in turn, inflation in the US economy.

This meant the Fed would have begun aggressive rate hikes during 2017, reducing some of the liquidity in the global markets and leading to a pull-back in the global carry trade.

But Trump’s failure to deliver on promises to dismantle the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare) has suggested that the promised fiscal expenditure and tax cuts are unlikely to be in the “quantum that was promised”, said Mhlanga. On Wednesday Trump announced his tax plans, which included steep cuts for corporates. But with concerns that the proposals lacked detail and may have trouble getting passed, US markets reportedly stayed a rally that had begun ahead of Trump’s announcement.

Should the policies ultimately disappoint, the expected inflationary impacts and rapid Fed hikes may be unlikely to materialise, he noted.

There was also the possibility that, if Trump’s fiscal promises did not materialise, US economic growth could decline, leading the Fed “to be even more dove-ish” than currently expected.

The yield on the local benchmark 10-year bond was about 8.7% this week, and the rand traded well over R13.20 to the dollar after the South African government’s excited tweet.

But, any weakness in the dollar off the back of news out of the US would aid the rand, noted Mhlanga.

He said that, besides dollar strength, two other important factors influence the exchange rate: commodity prices and local conditions.

Commodity prices, particularly towards the end of last year, have stabilised after a dramatic slump, which has also helped the rand.

Negative news on the local front — such as the credit downgrades by Fitch and S&P Global — has weighed on the currency, but now that this information is in the market, it has ceased to play such an important role in determining the currency’s value, added Mlhanga.

Meanwhile, commodity prices had softened after their recent rally, so dollar strength was the driving factor of the rand for the time being.

The hunt for yield would continue to boost South Africa, as long as it retained an investment-grade credit rating on its local currency debt. But should the country lose this rating and be removed from key global bond indices the effect would be far greater than what was seen after the recent downgrades, Mhlanga said.

After the recent Cabinet reshuffle, S&P Global announced it had lowered South Africa’s foreign currency credit rating to subinvestment grade or “junk” status, and its local currency rating to one notch above junk status. Fitch soon followed, downgrading its rating of South Africa’s foreign and local currency debt to junk. Moody’s has placed South Africa on review for a downgrade, but both its ratings for local and foreign currency debt stand two notches above junk.

The foreign currency credit rating applies to the debt a country issues in a foreign currency. In other words, it is the agency’s view of the ability of an issuing country to meet its loan obligations in a foreign currency.

The local currency rating applies to debt issued in a country’s own currency. South Africa has about R2.2‑trillion in government debt, with about 10% — or R220‑billion — in foreign currency. The rest is denominated in rands.

It is the local currency ratings by Moody’s and S&P Global that determine whether South Africa will remain included in key global bond indices such as the Citi World Government Bond Index.

Prior to the reshuffle, the rand had strengthened to about R12.30 to the dollar. Had the Cabinet changes and subsequent downgrades not happened, the rand could have performed even better, said Mhlanga.

Early this week, the rand also benefited after jitters over the outcome of the first round of the French elections eased. Centrist candidate Emmanuel Macron and far right politician Marine Le Pen will now battle it out in a run-off election in May, with Macron expected to win. This has reduced market fears over the threat of a French exit (Frexit) from the European Union.

Alongside the hunt for yield there has been an improvement in the general outlook for global growth, said Arthur Kamp, economist at Sanlam Investments. “Income growth has picked up this year, industrial production has been doing better and emerging markets globally appear to have bottomed out.”

The International Monetary Fund’s latest World Economic Outlook report estimated global growth for 2017 at 3.4%, rising to 3.6% in 2018.

Growth in major markets such as China has increased marginally, improving to 6.9% in the first quarter of the year — up slightly from 6.8% in the final quarter of 2016.

A slowdown in the Chinese economy, which Kamp said was constrained by overinvestment and high debt levels, was a risk to the improved view on global growth.

Equally, renewed policy uncertainty in the US or the European Union could also pose a risk to the growth outlook.

Against a backdrop of debates over events such as Brexit and Frexit in developed markets, emerging economies had benefited, said Iraj Abedian, chief executive of Pan-African Capital Holdings.

According to a research note from Nedbank, the MSCI World Index gained 5.9% in the first quarter of the year, and the MSCI Emerging Markets Index jumped by 11.1%.

“There were a lot of structural uncertainties in the developed economies that, by default, support emerging markets,” said Abedian.

Regarding allocations in emerging economies, he said that South Africa still compared relatively favourably with its peers such as Mexico, Turkey, Brazil and Russia, despite its problems.

“If you are a fund manager and you want to choose between emerging economies, South Africa is relatively better off,” he said.

Continued inflows into South African bonds rested on the “technicality” of the split between the rating of our local and foreign debt by major agencies. “We shouldn’t take comfort that we have a counterintuitive trend,” warned Abedian.

If circumstances change — particularly if the split in South Africa’s local currency ratings was resolved by a downgrade — things would change rapidly, he said.

“From the time that the ratings split disappears, the downhill will begin big time.”