The committee reviewing the country’s tax system has called for submissions on possible forms of wealth tax, despite the tax revenue already being almost 30% of its gross domestic product (GDP).

This week the treasury-mandated Davis tax committee said: “The distribution of wealth in South Africa is highly unequal, with recent empirical evidence suggesting that the Gini coefficient for wealth is about 0.95.”

The Gini coefficient is the variable used to measure inequality in a society. A score of zero means perfect equality and a score of one represents complete inequality.

The committee added: “It is well established that economic inequality inhibits economic growth and undermines social, economic and political stability.”

For this reason it is inviting submissions (before May 31) on the desirability and feasibility of the following possible forms of wealth tax:

• A land tax;

• A national tax on the value of property (over and above municipal rates); and

• An annual wealth tax.

At a tax-to-GDP ratio of 26%, South Africa’s tax revenue is already comparatively high.

To contextualise this, the developing economies of Turkey and Russia have ratios of 24.9% and 19.5% respectively. Nigeria, Africa’s largest economy, has a ratio of 6%.

Judge Dennis Davis, who heads the tax committee, said the role of the state should be considered when deciding what tax levels are appropriate.

“It all depends on what you do with the money,” he told the Mail & Guardian. “If you’re paying a huge amount on consumption expenditure then, yes, the percentage is high. But if the money goes to the restructuring of the economy to ensure an inclusive growth path, then we shouldn’t be hung up with that unduly.

“I don’t suggest we are spending our money as well as we should, but we can and we must direct money to capital expenditure to redress the past.”

The committee first raised discussions around a wealth tax about a year ago. This followed a treasury-funded research report that looked at wealth rather than income as a measure of inequality.

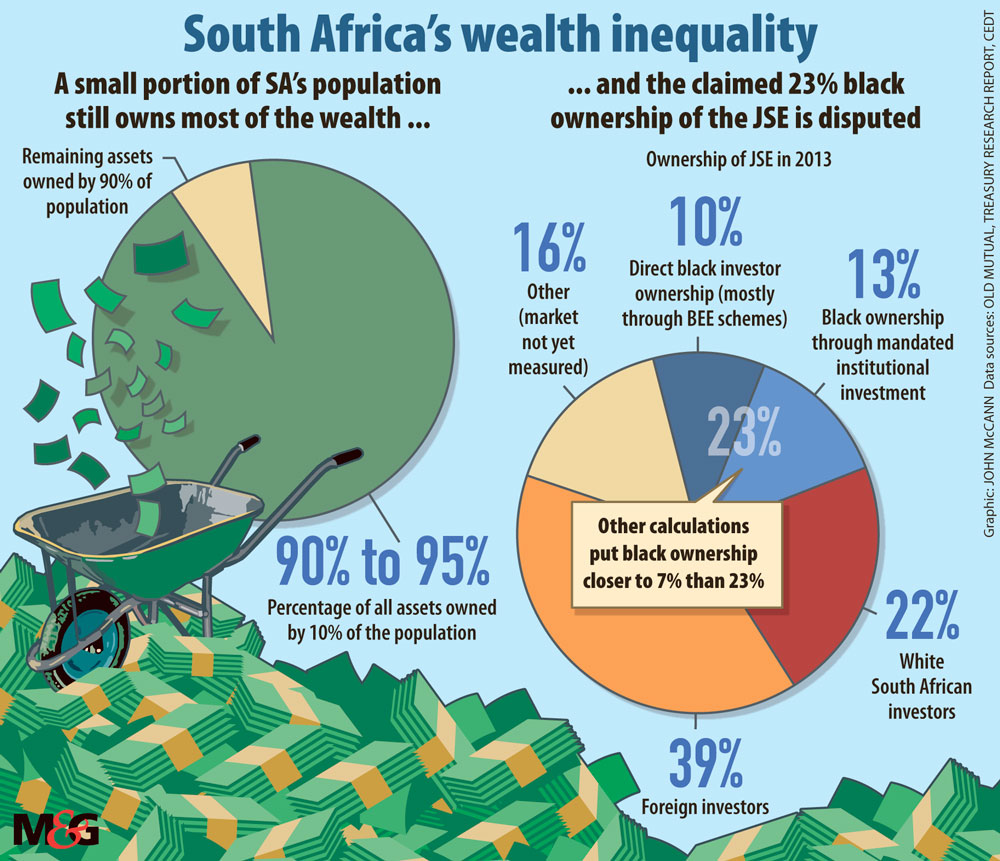

The research findings “suggest that 10% of the population owns at least 90% to 95% of all assets”, wrote author Anna Orthofer. “Although the top income shares are very high in their own right, they pale in comparison with the top wealth shares.

“Compared to income, wealth is much more concentrated in the hands of the few.”

Income distribution is also highly unequal. Calculations of a traditional income-based Gini coefficient vary from between 0.59 and 0.7, depending on what is included.

Both the wealth and income Gini coefficients “are higher than in any other major economy for which such data exists”, the study said.

Orthofer measured wealth distribution among the various races. “I find that white and Indian households are still much wealthier on average than Africans and coloured households,” she said.

“However, wealth inequality within the majority black population exceeds nationwide wealth inequality by far. The African distribution is much wider than the white distribution, showing that the disparity between rich and poor African households is larger than that among white households … The highest wealth inequality is found within the African group.”

Jannie Rossouw, head of the school of economic and business sciences at the University of the Witwatersrand, believes the key to shifting inequality lies with cultivating a middle class.

“Our challenge in South Africa is to grow the middle class as fast as we possibly can — people that live decently and demand basic goods and services in the economy; people that can be serviced by entrepreneurs in the country.”

By all accounts, the black middle class is growing quickly. A Unilever study in 2013 showed that the group had more than doubled over the past eight years (to 4.2‑million people) and had seen an average income increase of 34% in that period.

“The current indications are that the black middle class is bigger than the white middle class,” said Rossouw. Nevertheless, the ideal growth path would be steeper. “I would want to see much quicker growth if for no other reason than to increase the tax base. With only 6.7‑million direct taxpayers, it is under considerable pressure.”

So, how effective have policies aimed at wealth redistribution been over the past 24 years? How happy would the average black South African be with the changes?

“It depends who you ask,” said Rossouw. “If you ask Cyril Ramaphosa, he would be happy. If you ask the desperate, hungry person begging on a corner, he would not.”

A 2016 interview-based survey involving 2 245 respondents, conducted by the South African Institute of Race Relations, found that 85% had “gained nothing” from policies of redress such as broad-based black economic empowerment (BEE).

About 17% of black respondents agree that affirmative action in employment has helped them personally. “By contrast, 83.3% of blacks disagree with it,” said the institute’s policy head, Anthea Jeffery. “Only approximately one in 10 people has benefited from broad-based BEE.”

Just over 11% said that land reform had “helped them personally”. Only 2% said that more land reform would “help improve their lives”.

According to Orthofer’s research, the shift has been barely perceptible. Her findings “suggest that South Africa has not yet experienced a comparable transformation”.

“While there may be a growing middle class with regard to income, there is no middle class with regard to wealth: the middle 40% of the wealth distribution is almost as asset-poor as the bottom 50%.”

A 2013 assessment by the JSE found that black South Africans control about 23% of the JSE — 10% of which was direct black investor ownership and 13% of which was “black ownership through institutional investment”. Notwithstanding that a large portion of the JSE is foreign-based, this finding might suggest the country is on track to meet the government’s goals, which aimed for black people to own 25% of the South African economy by this year.

Duma Gqubule, founder of the Centre for Economic Development and Trans-formation, says there are several flaws in the JSE’s calculations.

“My problem with the indirect shareholding is that it is probably mostly counting the PIC [Public Investment Corporation]. That money shouldn’t be seen as belonging to the beneficiary; it belongs to the government. So I don’t think we should be counting it.”

Gqubule’s calculations pitch gross black ownership of the top 40 companies on the JSE at 6.5% of South African assets. “We are way below the direct ownership target of 25%,” he said. “We still have a way to go.”

Gqubule said some BEE ownership deals had been successful in their aims to empower South Africans. “The biggest myth is that the shares [from BEE deals] have gone to the politically connected. The beneficiaries vary. For example, MultiChoice’s R2.25‑billion deal benefited the man on the street.”

The social grant programme is helping to address poverty. Rossouw said “social grants are the best poverty alleviation project of the government. There are 17‑million beneficiaries — about 30% of the SA population.”

The treasury declined to comment on whether policies are adequately addressing wealth redistribution. The department of trade and industry did not respond to a request for comment on the effectiveness of broad-based BEE.

Assessments of current levels of success vary, but all figures indicate that more needs to be done to distribute wealth more equitably.

In Gqubule’s opinion, keeping the interest rate low is key.

“Inflation targeting has impeded capital accumulation,” he said, adding that the average interest rate since democracy has made “the cost of capital too high for people to accumulate wealth”.

The Institute of Race Relations says “the answer lies in shifting away from BEE and other race-based policies and embracing a new system of ‘economic empowerment for the disadvantaged’ ”, or EED.

This “cuts to the heart of the matter by focusing directly on disadvantage and using income and other indicators of socioeconomic status to identify those most in need of help”.

The institute added that EED would not focus on outputs in the form of numerical quotas, but rather on providing the inputs necessary to empower poor people.

In Rossouw’s opinion, “the best way to redistribute wealth, of course, is to get people employed. If they are employed, they can start building assets.” But “we also need to act against corrupt politicians,” he said. “That is where the rot starts.”