Last year I began cutting back on my daily office pick-me-up – a takeaway latte. Instead, I bought refill packs of instant coffee, which cost the equivalent of two lattes. What I used to spend in two days I now stretch for a few weeks.

This decision is hardly a matter of life or death. Many South Africans make the choice between not eating today so they can afford to get to work tomorrow – if they have a job.

But if this week’s gross domestic product (GDP) numbers reveal anything, it is that the last straw has broken the stressed consumer’s back. They suggest these sorts of cutbacks are taking place in most households.

The economy shrank by 0.7% in the first quarter of 2017, despite expectations that it would grow by about 0.9% off the back of a recovery in agriculture and mining. But the tertiary and secondary sectors showed major declines, Statistics South Africa said this week.

Manufacturing, which contributes about 13% to GDP, shrank by 3.7%, after two previous consecutive quarters of decline.

The trade, catering and accommodation sector, which makes up about 15% of GDP, shrank by 5.9%.

Finance, retail and business services, which contribute about 20% to the GDP, shrank by 1.2%, the first contraction for these industries since the last recession, which followed the financial crisis in 2008 and 2009.

About 60% of GDP is driven by the consumer and “the consumer stopped spending”, said Maarten Ackerman, Citadel’s chief economist.

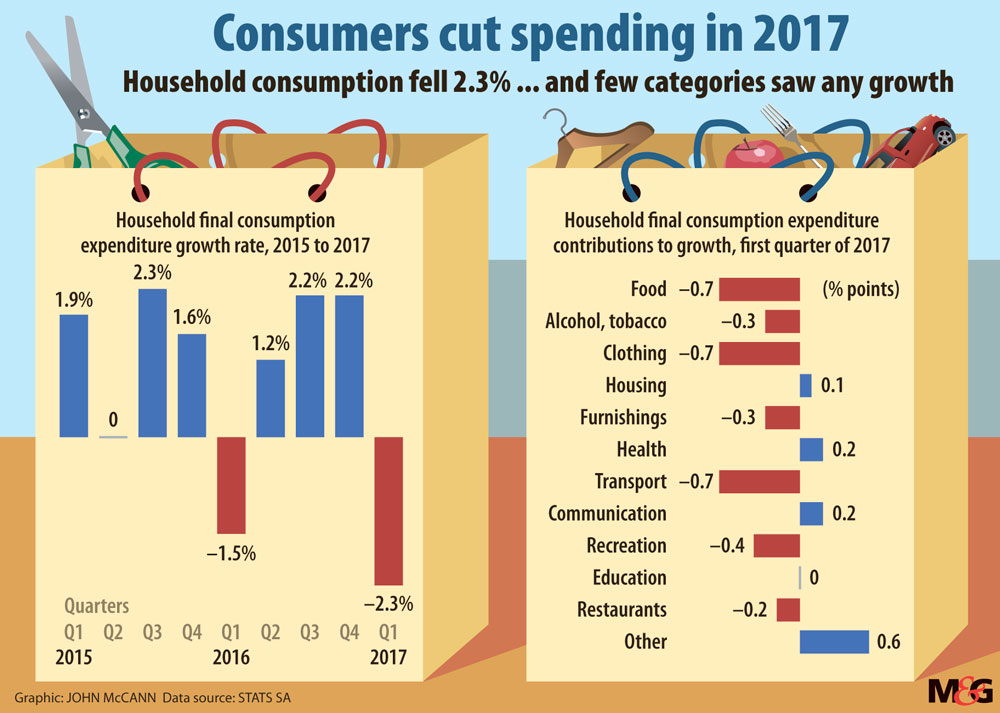

In terms of expenditure on GDP, household consumption in the first three months of this year declined by 2.3%. Households cut spending on food, restaurants, recreation, transport and clothing. The few positive contributors to household expenditure included housing and health.

I asked a group of friends whether they have recently made noticeable changes to their spending habits. All are employed and, although this was hardly a representative sample of consumers, most have slashed spending. Savings ranged from cutting out luxuries to buying in bulk. One friend described her efforts to save more on food by freezing it as “post-war frugal”, and another summed up her experience as “working harder and feeling poorer”.

The malaise in consumer and business confidence began before former finance minister Pravin Gordhan was fired in a late-night Cabinet reshuffle, a move that resulted in ratings downgrades by the agencies Fitch and S&P Global, Ackerman argued.

Although South Africa has now entered a technical recession (defined as two consecutive quarters of negative growth), “we were already in a recessionary environment”, he said. After Gordhan’s predecessor, Nhlanhla Nene, was axed at the end of 2015, South Africa became what he termed a “wait-and-see economy”.

New capital expenditure by business, local and foreign direct investments and consumer consumption have all declined, weighed down because of political and policy uncertainty.

“People have been saying, let’s wait and see what’s going to happen [before we spend],” Ackerman said.

The firing of Gordhan and the downgrades, which all took place in the second quarter of the year, are clouding the outlook for economic recovery. “Consumers are probably going to be more negative now and more cautious on spending,” he said.

The growth figures follow the latest unemployment numbers, which rose to a record high of 27.7% in the first three months of the year.

The ailing economy goes hand in hand with South Africa’s political dynamics, according to Iraj Abedian, the chief executive of Pan African Investments & Research.

The recent release of the explosive email cache, which appears to back allegations of the Gupta family’s capture of the state and its agencies, has dominated headlines.

“When the national political economy milieu is as uncertain as we have had it, and when unemployment continues to rise, consumer confidence tanks,” Abedian said.

This is reflected in contractions in all areas considered “non-essential”. “Consumers scale down in quality and in spending and focus on essentials,” he said. The rate of capital formation is equally muted and suggests, “going forward, the investor confidence is also low”.

According to Stats SA, gross fixed capital formation rose just 1% in the first quarter of 2017. It followed three quarters of negative growth before expanding by 1.7% in the last quarter of 2016. This creates a negative “feedback loop between consumer confidence and investor confidence, leading to a downward spiral in the broader macroeconomic environment”, Abedian said. This is happening in an environment where global factors should be playing in South Africa’s favour, he said.

The erratic leadership of United States President Donald Trump and concerns over Brexit and the European Union have contributed to “a discount on developed country markets in favour of funds flowing into emerging economies, including South Africa”, Abedian said.

When the president is preoccupied with Cabinet reshuffles and ministers are “busy with scandalous management of the [state-owned entities] and their departments”, the local economy is neglected, investors are rattled, and policies are “left in the air. In short, the recession is entirely home-made.”

The depth of the recession remains to be seen. If Moody’s, which is yet to pronounce on South Africa’s credit rating, downgrades the country to subinvestment grade “then our recession will deepen sharply”, Abedian said. If not, and barring any further state scandals, the economy could “wallow in shallow recession”.

Nerina Visser, a strategist and adviser at etfSA, said the recent figures also speak to a more fundamental problem – South Africa’s failure to invest in productive capacity.

“A lot of South Africa’s growth has come from consumption expenditure, rather than investment in infrastructure and productive capacity, which, over the long term, result in more sustainable economic growth,” she said.

Both the state and the private sector share responsibility for this failure, she said. The private sector can’t always hide behind the argument that it needs to “create shareholder value and therefore can’t invest under current conditions”.

The large cash reserves on corporate balance sheets is a case in point, she said. According to data from the South African Reserve Bank, this amounted to about R719-billion in February.

Ackerman said there are “green shoots”, given the improvements in the agricultural and mining sectors and an upswing in global growth. Previously these factors have underpinned growth and could be enough to see positive second-quarter growth figures coming off a low base.

But, without restoring business and consumer confidence, the economy is more likely to remain in the wait-and-see pattern, he said.