The Fiat Tagliero garage resembles an aeroplane.

The Fiat Tagliero in Eritrea is described as the world’s most beautiful petrol station. Built to resemble an aeroplane in flight, with 18m solid concrete wings that soar over the pumps below, the building is an iconic example of the Art Deco architectural movement.

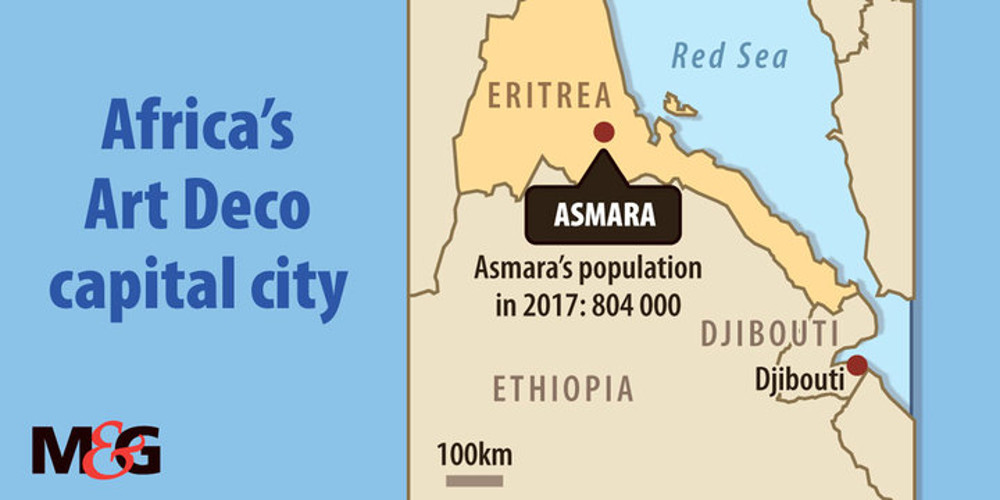

It is one of many such icons in Asmara, the capital of Eritrea.

[Graphic: John McCann]

Local legend has it that when the Fiat Tagliero was being built in 1938, Eritrean engineers were worried that those extraordinary, cantilevered wings could not possibly support their own weight, and were reluctant to remove the scaffolding. Architect Giuseppe Pettazzi had other ideas. Pulling out a gun, he threatened to kill himself if the building collapsed. He didn’t have to.

Pettazzi was one of the many crazy, unorthodox and talented Italian architects shipped off to Eritrea in the 1930s. Too risqué for Italy proper, they were tasked by fascist dictator Benito Mussolini with creating a “Piccolo Roma”, or little Rome, in the Horn of Africa.

What they created instead was one of the world’s most unusual cities, and also one of its most magnificent: a futurist, Art Deco-inspired metropolis that has maintained its beauty, and its grandeur, through decades of war and repressive regimes.

[Photo: Thomas Mukoya]

After years of lobbying by the Eritrean government, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (Unesco) finally anointed Asmara as a World Heritage Site last week. “It is an exceptional example of early modernist urbanism at the beginning of the 20th century and its application in an African context,” said Unesco in its official inscription.

The Italians designed more than 400 buildings in a construction boom that was only halted by Italy’s involvement in World War II. These included government offices, churches, mosques, synagogues, hotels and residential areas. Most were intended to project the power of Mussolini’s fascist state.

“Monumental buildings were meant to dwarf you when you go in and emphasise the power of the occupant. You could almost imagine ‘Il Duce’ [Mussolini] striding out,” said Samson Haile Theophilos, an expert on Eritrean architecture, speaking to Reuters.

But while Italians may have come up with the blueprints, it was Eritreans who did the construction. “The Italians felt they would be here for hundreds of years, so they built and built, and left us this remarkable legacy,” said Theophilos. “But I want to stress that the workers, skilled and unskilled, were all Eritrean, so we consider this architecture ours.”

[Photo: Radu Sigheti/Reuters]

Hanna Simon, Eritrea’s representative to Unesco, said the decision is a victory “not only for the Eritrean people, but for the world”. Simon stresses that edifices such as the central mosque, the Fiat Tagliero garage and the central post office “serve as a symbol of joy for the Eritrean people”.

Besides global recognition, being a World Heritage Site should translate into practical benefits for Asmara; Unesco can step in to preserve buildings if they are in danger of deterioration.

It may also increase the country’s tourism potential: currently, sightseers are mostly honeymooning couples from neighbouring Sudan.

Of course, attracting people to visit Eritrea is a secondary concern for the Eritrean government, which is struggling with a more immediate priority: persuading Eritreans to stay. Tens of thousands of Eritreans have fled the country, with more following every day, to risk uncertain futures in Ethiopia, Sudan and, eventually, Europe.

They are escaping from what is often described as the “North Korea of Africa”: a dysfunctional dictatorship run by President Isaias Afwerki that enforces indefinite military conscription, routinely jails and tortures political opponents and has shut down all independent media.

Maybe Asmara’s architecture is not the only thing inspired by Mussolini.