(John McCann)

“Swallowed in the shadows that glow” — Twilight, Antony and the Johnsons

I was lucky. I had fallen into a “G sleep” — a potentially fatal state of unconsciousness triggered by an overdose of the sex drug GHB — and woken up drowsy, naked and in the bed of a stranger. But I was alive, unharmed.

I had met the stranger through the gay dating app, Grindr. The purpose of the hook-up was for more than merely sex, but for a “Party and Play” — a “chemsex” — session.

As I left his apartment, stepping out onto the strange street, haggard, high and humiliated, I decided then — hoped then — that this would be the last time.

Chemsex is sex between men that happens under the influence of drugs.

Different to the more traditional intersection between drugs and sex, where sex is not the central reason for taking drugs, with chemsex drugs are consumed with the intention of having sex. Meetings are organised primarily through dating apps such as Grindr, using keywords such as “Party and Play” or “chemfun”. People’s online dating app profiles make their intention clear: men would meet up for the express purpose of using drugs and having sex.

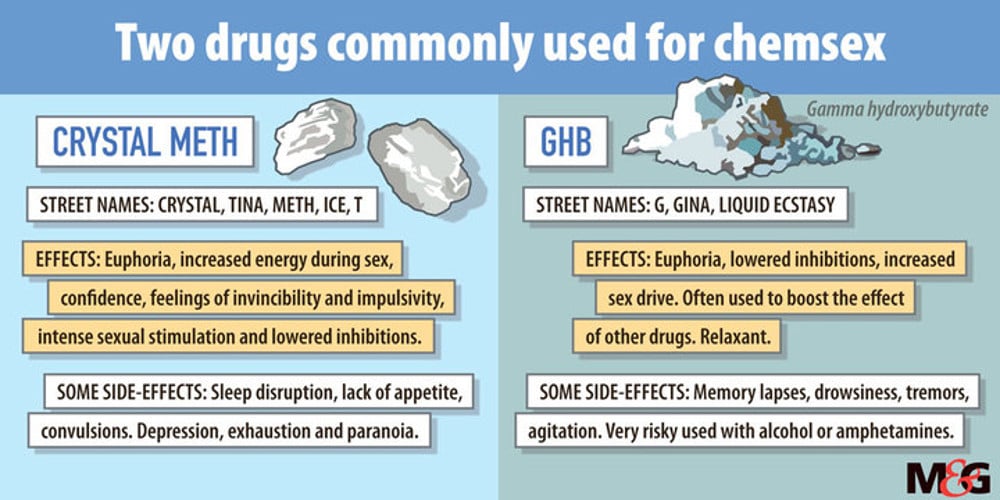

Drugs used primarily during chemsex sessions are crystal methamphetamine (crystal meth) and GHB, or gamma hydroxybutyrate, also sometimes known as “G”.

There is very little data on the extent of chemsex in South Africa. But a 2014 UK study, published by Sigma Research and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, found that the practice was increasingly common — although evidence of drug use during sex in the UK was also limited.

“Nearly all crystal meth use was reported within sexual settings, while 85% of GHB users said they used the drug solely to facilitate sex,” the report stated.

Deaths as a result of overdosing on GHB are not uncommon.

A 2017 study published in the Forensic Science International journal found that, from 2014 to 2015, GHB-related deaths in London had risen to 29 — up by 119%.

Because chemsex sessions often take place over many hours — even days — and involve numerous sexual partners and participants often engaging in unprotected sex, the risks of HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are also higher.

“God knows what all these new drugs do / I guess to have no more fears / But still I always end up in tears” —Vibrate, Rufus Wainwright

During his eight months of homelessness last year (“my meth addiction became that out of control”), Clive Adams* went from more than being a mere participant in chemsex parties to actively organising them.

“I was basically the middleman,” he says. “People would tell me their fantasy and I would set it up. You want a 10-man gangbang? I’m your man. And let me tell you, people are willing to pay,” he says.

Adams, who asked to remain anonymous, adds that a focus during his days as middleman was putting together chemsex parties for men who, like him, were HIV-positive.

“I was organising parties for HIV-positive breeders — men who want to infect others or be infected.

I thought I’d rather fuck with my own kind. But what that means, of course, is being exposed to different strands of HIV.”

People living with HIV can contract additional strains of the virus that may complicate treatment and lead to drug resistance.

Six years of sustained crystal meth use, frequent unprotected sex with numerous partners and not adhering to his required daily dose of antiretrovirals (ARVs) saw Adams’ health severely affected.

Waiting in line at Helen Joseph Hospital’s ophthalmology unit, Adams says: “I just kept putting taking my meds off. Eventually, my lifestyle became so out of control that

I developed beads under my skin — on my hands and feet.

“They looked like pimples, but it was actually acute syphilis, which I got from all my, you know, unsafe sex practices. Those beads eventually cracked open and the skin became like hard calluses. I couldn’t walk. I couldn’t use my hands. I was in hospital for the month of February. The whole month. I was in severe pain.”

Although no longer an active user, (“I’ve been clean for four months now … hallelujah, Jesus,” he laughs), his years of not taking his ARVs properly has resulted in his body building up a resistance to his medication.

When people frequently skip ARVs, they develop resistance and must be moved on to different, typically more expensive and harsher drugs.

“My doctors told me, ‘You either shape up or you die’, because this is the last cocktail of meds they can put together for me. After this, nada. I either stick to this or die. That’s what it boils down to.”

In addition to unprotected sex, the risk of HIV is increased when chemsex participants inject crystal meth, commonly referred as “slamming”.

“Disappear Here. The syringe fills with blood. You’re a beautiful boy and that’s all that matters. Wonder if he’s for sale. People are afraid to merge. To merge.” — Less Than Zero, Bret Easton Ellis

Eighty percent of men surveyed in the 2014 UK study who reported using crystal meth before or during sex did so intravenously.

“Look at my veins. Feel them,” Paul Schwarz* says, pulling up his sleeve. “They’re fucked up. They’re so hard I can’t use them anymore. In fact, the only ones I can use are the ones I can’t reach.”

Ten years after starting to use — and eventually moving on to injecting— the drug, Schwarz, who also chose to remain anonymous, has finally decided to stop.

“I never thought I’d slam,” he says. “But one day I asked someone why they did it and they said, ‘The rush.’ So I tried it. The fact is you can’t compare that rush. But it’s really a story of diminishing returns, because you keep chasing that first high. But it’s never as good as the first time.”

Having given up on chasing the initial high, the self-described “ex-meth-odist” says: “For a long time, I thought it didn’t affect me and that colleagues couldn’t tell. One day, someone who didn’t work with me but came to the office often referred to me as ‘that guy that’s always high’. I realised then that if she could see it, then anyone could. And that’s the thing with the drug: you become so out of touch.

“Also, slamming keeps you in this ghetto of crystal-only people. And, mostly,” he laughs wryly, “they’re not a very nice bunch of people.”

Schwarz says he now only does G.

“It knocks me out. Nobody tells you that if you’ve been doing crystal for such a long time, even after you have stopped using, you don’t get to sleep properly again. Sleeping pills don’t work. So I do G now. It’s an expensive sleeping pill, but it knocks me out. I’ve now got a lot of my life back.”

Yet the use of GHB can be potentially very dangerous — “because the threshold between the high and the overdose is so narrow,” says Evan Tsouroulis of Anova Health’s Health4Men.

According to the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine study, “just a small overdose (as little as half a millilitre) can lead to a ‘G sleep’ — a state of unconsciousness in which the individual requires careful monitoring to avoid choking, and higher doses can lead to respiratory depression”.

Tsouroulis adds: “Even though people know the risk, they will often take that risk.”

Recognising the need to inform drug-users of these risks, Health4Men initiated a harm-reduction programme for people who use drugs in 2013. Harm-reduction initiatives are policies, programmes and practices that aim to reduce the harms associated with drug use. Essential as the project was, it proved to be a difficult sell.

“The pain and fear that in his mind reside / From dawn ‘til dawn his body houses hurt / And none of us can truly aid his search / We sit outside and sing clichés, ‘the fool’ / It’s always easy to forecast others doom” — The Crutch, Gil Scott-Heron

“Initially, it was difficult to get buy-in from a range of people, including our target communities. We would hear things like, ‘We don’t have a problem’ or ‘You’re tarring us all with the same brush’ and ‘You’re making the gay community look bad’. But this is really a denial of the extent of the problem,” says Tsouroulis.

Health4Men’s Kevin Rebe adds: “The other thing to remember is that harm reduction in South Africa is not an entrenched concept. So we see quite conservative attitudes and puritanical discussions. It’s a bit like [preaching] abstinence to not be infected with HIV, which doesn’t acknowledge that people have sex.

“It’s the same with drugs: people are reluctant to admit that there is a problem. When looking at men who have sex with men, they’re already a stigmatised population — already getting a raw deal — and the last thing they want is for someone to say, ‘Now we’re associating you with drug use as well’.”

Rebe stresses, however: “What we’re interested in at the end of the day, is healthy, happy moffies. We’re interested in patient health outcomes and quality of life.”

Rebe says the medical literature “is clear”. The ongoing discrimination and stigma throughout their lives has an internal effect. It leads to conditions like depression, anxiety and stress. “People will often be self-medicating with their drugs.”

The pilot project, which ran until 2014, included the collection of data that has now been used to kick-start the Jabsmart programme.

Glen de Swardt, programme manager for Health4Men, says the project is “starting very slowly”, kicking off in Hillbrow, Yeoville, Berea, Braamfontein and Johannesburg’s inner city.

Aimed not only at men who have sex with men, it includes mobile clinics that offer HIV and STI testing and employs peer educators who “know the networks”. The aim is improved health “through the provision of a nonjudgmental service”.

“Our intention isn’t to tell people to stop using drugs. There is no moralising, because the reasons why people use drugs are very complex,” says De Swardt.

Rebe adds: “People use drugs because it feels good. That is the bottom line. But if, for example, all your life you’ve heard how evil you are, how wrong, how un-African, unChristian or un-Muslim you are and you’re suddenly supposed to be this confident person … People often don’t have the emotional resources to do that. The drugs often provide it.”

Rob Hamilton, a clinical psychologist specialising in harm reduction, says: “The use of drugs offers a way of working through the anxiety of getting intimate with others. It is disinhibiting, which to many is a great attraction. It also fills a gap for those who struggle with loneliness or a sense of not connecting with other people.”

He adds that, “if used sensibly and in a controlled fashion, the recreational use of drugs could be fine”.

“But when it starts taking up more and more of your time, then it starts becoming an issue.”

Schwarz says: “What I had to teach myself with crystal is that, amazing as it is, it’s just a feeling. It’s not an experience. It’s not something to build my life on. It’s not a win or an accomplishment … And when one is trying to stop it, that’s the thing to remember: all you’re giving up is a great feeling. And if you think of losing your family, your friends, your career … that’s a lot to trade for.”

My sojourn into the world of chemsex behind me, I was fortunate enough not have reached a point where I had to trade friends or family for the fleeting feeling; the vacuum it temporarily filled.

But had I inadvertently made other trade-offs?

“No one knows when their time will come; some people choose to die earlier, earlier than their time. Some people wish to live forever, to never die. But we will all die.” — Youssef Nabil

The 15 minutes waiting for my HIV test result at the Yeoville clinic felt like an eternity. An anxiety-filled eternity filled with sweaty palms and forehead-smiting recollections of self-destructive moments with nameless strangers and things I had done that brought me to this point.

“Bhuti, you can come in now,” the health worker summoned me into the tiny room where she had, minutes earlier, drawn my blood.

As she told me the result, the shock too much for me, I cried.

She hugged me and laughed: “So you have heard good news today. Now you must start protecting yourself. OK?”

I nodded obediently, knowing that, again, I had been lucky. I was a lucky fool: lucky to have stumbled away from my chemsex journey unscathed. A fool to have started in the first place.

* Not their real names

Carl Collison is the Other Foundation’s Rainbow Fellow at the Mail & Guardian