During the shootout eight suspects were killed and two are in a critical condition and one of the five police officers who was wounded has died.

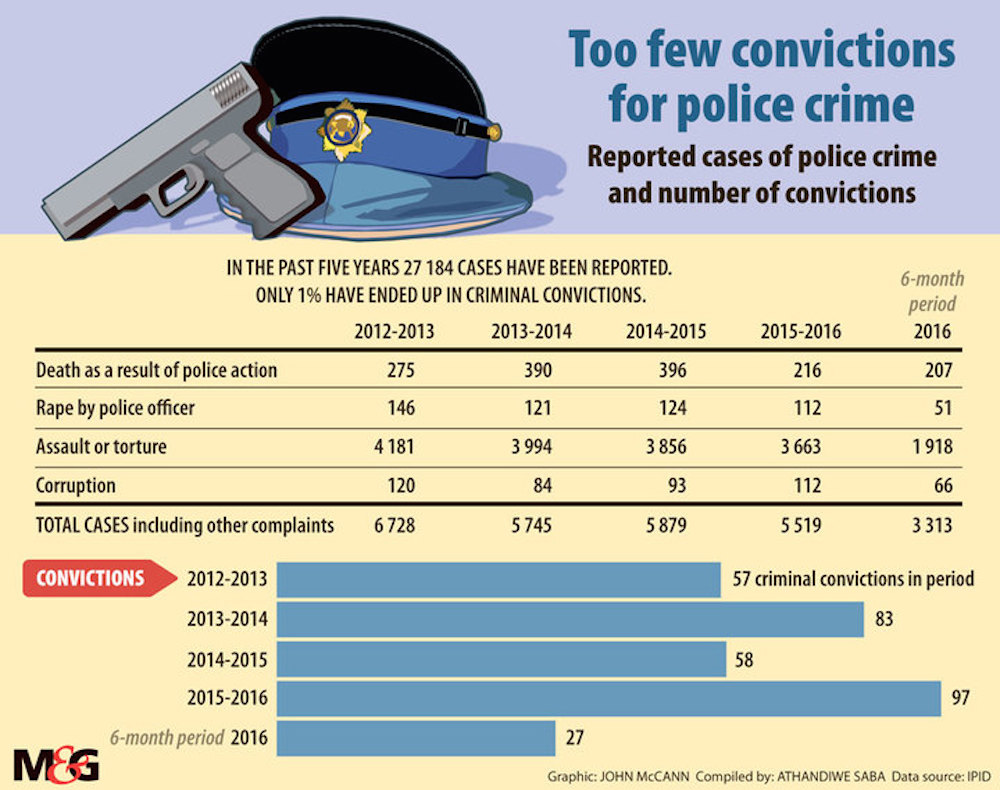

In the past five years only 1% of the thousands of cases reported to the Independent Police Investigative Directorate (Ipid) have resulted in criminal prosecution.

Many of the cases drag on for years, with a low case turnover and even fewer convictions.

One of the most glaring examples of this and police lack of oversight is Captain Morris “KGB” Tshabalala, who, with at least two criminal convictions, for armed robbery, masterminding a cash-in-transit heist and attempted murder, was able to work for crime intelligence and get the highest clearance in the police service.

But the Ipid also seems to have problems convicting officers for assault and torture, rape, corruption and murder. Last year the directorate reported it had received 216 complaints where a civilian had died as a result of police action. Also last year, the Ipid managed to convict 13% of the officers implicated in such cases.

According to the watchdog’s mid-year statistics for 2017, the number of convictions is even lower.

Tshabalala is one of the many officers who have either committed crimes or are alleged to have done so, and yet neither the police service nor the police watchdog has ensured he is no longer part of the service.

However, SAPS spokesperson Sally De Beer said that he was no longer part of the service, but they would make further inquiries and revert to the Mail and Guardian.

The man, better known as “KGB”, became known to the police in 1994 when he was arrested for an armed robbery in Mamelodi, Tshwane.

After a lengthy court case Tshabalala was convicted of robbery and handed a 10-year sentence. Police records show that Tshabalala spent two weeks in prison before being released pending the outcome of his appeal. By 1998, when his appeals had failed, he had disappeared. Officially, the police service is still investigating.

According to crime intelligence sources, Tshabalala entered the police force in 2002.

“I knew this guy and I knew he was a criminal, but who am I to speak above the bosses who think he was the right guy for the job?” said a source who did not want to be named. “But I was shocked when, in less than a year, he was promoted to captain. He knew some high-up people and even though he didn’t have the experience he knew the right people.”

During his time in crime intelligence Tshabalala was given the highest clearances and worked on high-profile cases, including the foiled assassination attempt on President Jacob Zuma at the ANC’s Mangaung conference in 2012.

A year later Tshabalala was apparently back to his old tricks — heists.

He and five other accomplices were arrested in 2013 for allegedly robbing a cash-in-transit van carrying R3-million in Sasolburg, and attempting to murder one of the security guards. He was also being investigated for links to numerous other heists.

With his name and face splashed across newspapers and with another case to answer for, KGB was imprisoned to serve his 1996 sentence while his trial for the more recent heist continued.

South African Police Service, Hawks and National Prosecuting Authority officials told reporters at the time that a full investigation was being conducted to determine how Tshabalala had escaped from under their noses.

Last year, after serving less than three years at Sasolburg’s Groenpunt Correctional Centre, he walked free — straight back into his old job at the police service.

“He was back again. He was not an officer, but everyone knew he was back. But we mind our own business in there,” said a source.

All was quiet for a few months until R200-million in foreign currency was brashly stolen from Johannesburg’s OR Tambo International Airport by a group of men driving a stolen police van and two smaller cars.

It has been widely speculated that KGB was the mastermind behind the heist and an investigation into his involvement is underway.

He was handed a suspension letter shortly after the news of the heist broke, according to sources in crime intelligence.

“The Ipid is currently conducting an investigation into various allegations in which Tshabalala may be implicated. Due to the sensitivity of the investigations, we cannot comment without jeopardising our investigations,” said Ipid spokesperson Moses Dlamini.

The police watchdog has repeatedly pointed to its limited resources — including only 165 investigators and an ever-decreasing budget —as a constraint to realising their mandate.

“The Ipid has never had sufficient resources from its establishment. In addition, our budget was cut over the past three years. With the resources we have, it is difficult to complete or finalise all investigations as swiftly as we would like to,” said Dlamini.

But finances are not the only problem. The KwaZulu-Natal Ipid ethics head, Amar Maharaj, this week told the Moerane Commission of Inquiry into political killings that the police watchdog was “dysfunctional”.

He said that hundreds of cases had been closed without proper investigation and that the officers who closed them were given bonuses for finalising cases.

SAPS had not replied to questions by the time of publication

‘I wasn’t a criminal, yet the police treated me worse than one’

IRVIN DALAIS:

Strangled and beaten at Mondeor police station

Case unresolved

[Beaten: Irvin Dalais says he was trying to report a domestic dispute when police officers attacked him in the police station. (Photo: James Oatway)]

The police were called to my house on an afternoon in May for a domestic disturbance. I didn’t want to be arguing with the police in front of my children so I volunteered to drive myself to the police station.

I was calm at all times because I know how aggressive the police officers at Mondeor police station can be. When I arrived at the police station to make my statement one officer leaped towards me and grabbed my arm and pinned me to the wall. He handcuffed me, like I was a common criminal, even though I had driven myself to the station. After handcuffing me he started choking me and throwing me on desks.

I used to be an officer myself and I know what protocol is. I was not a criminal, yet they treated me worse than that.

I was in shock that I would be assaulted this way in a police station in front of witnesses. It was only after I had a few bruises that one of the officers pulled his colleague off me.

The handcuffs were taken off me, but then the challenge was actually opening the case because everyone refused to assist me.

After at least two hours did I find a number on the notice board for the station commander and he was the one who instructed a captain to open a case.

It took the police station two months to get back to me with a case number, which goes to show how little they cared about a case opened against one of their own.

The case has reached the Ipid [Independent Police Investigative Directorate], but not a single person has contacted me since the incident

LUCKY NGELE:

Shot by police officers

Case unresolved

[In the wrong place: Lucky Ngela was on his way to a match when he was shot in the leg by police dispersing a crowd. (Photo: James Oatway)]

The week before we [his football team] had just made it into the top four and that Sunday we were going to play our game to ensure we were in the finals. But it wasn’t to be. As I was making my way to the field to warm up for the game I noticed that there was a crowd gathering. I asked a few people what was going on and learned that the community was about to beat up a known thief who they said had raided someone’s house.

Before I could find out more, the police had arrived in vans to save the thief. But the community didn’t disperse. I was quite far away from the crowd but when I heard the gunshots I ran towards an area with trucks to hide. When I cowered behind one of the trucks I felt what I thought was my phone vibrating. It wasn’t my phone.

People started running in all directions and I followed until I stopped at a spaza shop where a friend of mine told me that I had blood on my leg. I had been shot.

I was rushed to the hospital and the bullet was removed. We tried to follow up the case, going as far as the local Ipid office, but after two years we were told by the investigating officer that the docket had disappeared. The police are not meant to fire live ammunition to get rid of a crowd; many more people could have died that day. But there is no justice for us poor people. — As told to Athandiwe Saba