Painting through struggle: Fatima Meer's work represents the harsh realities of prison and how she

When I first came across Fatima Meer’s paintings in 2008 I had no idea they would inspire my master’s degree. I had just been appointed the exhibitions and archives co-ordinator for the Women’s Jail and had enrolled for an MA in arts and culture management and heritage studies.

After seeing five of Meer’s paintings displayed at Constitution Hill that year, discovering that there were more paintings during my research felt a lot like crawling into the walls of the Women’s Jail and listening to the many voices trapped between the cracks of this historical site.

Meer, a mother, sociologist, academic and activist, was a heroine of the anti-apartheid movement. She was banned, detained and jailed for her activism, which also led her to co-found in 1973 the Black Women’s Federation, an organisation focused on addressing the social, political and economic issues that affect black women. Meer was its first president.

[Fatima Meer. (Photo: Gallo Images)]

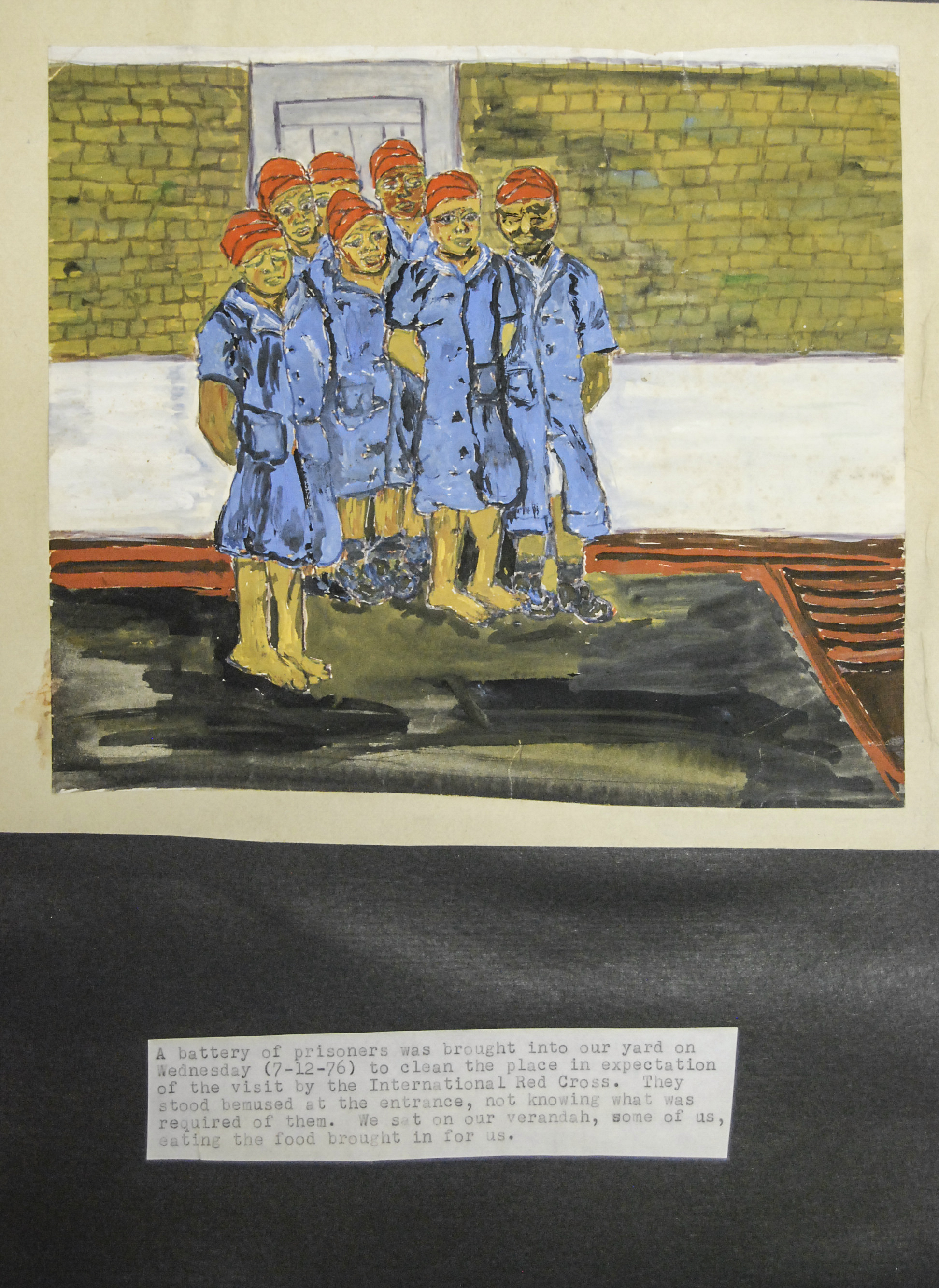

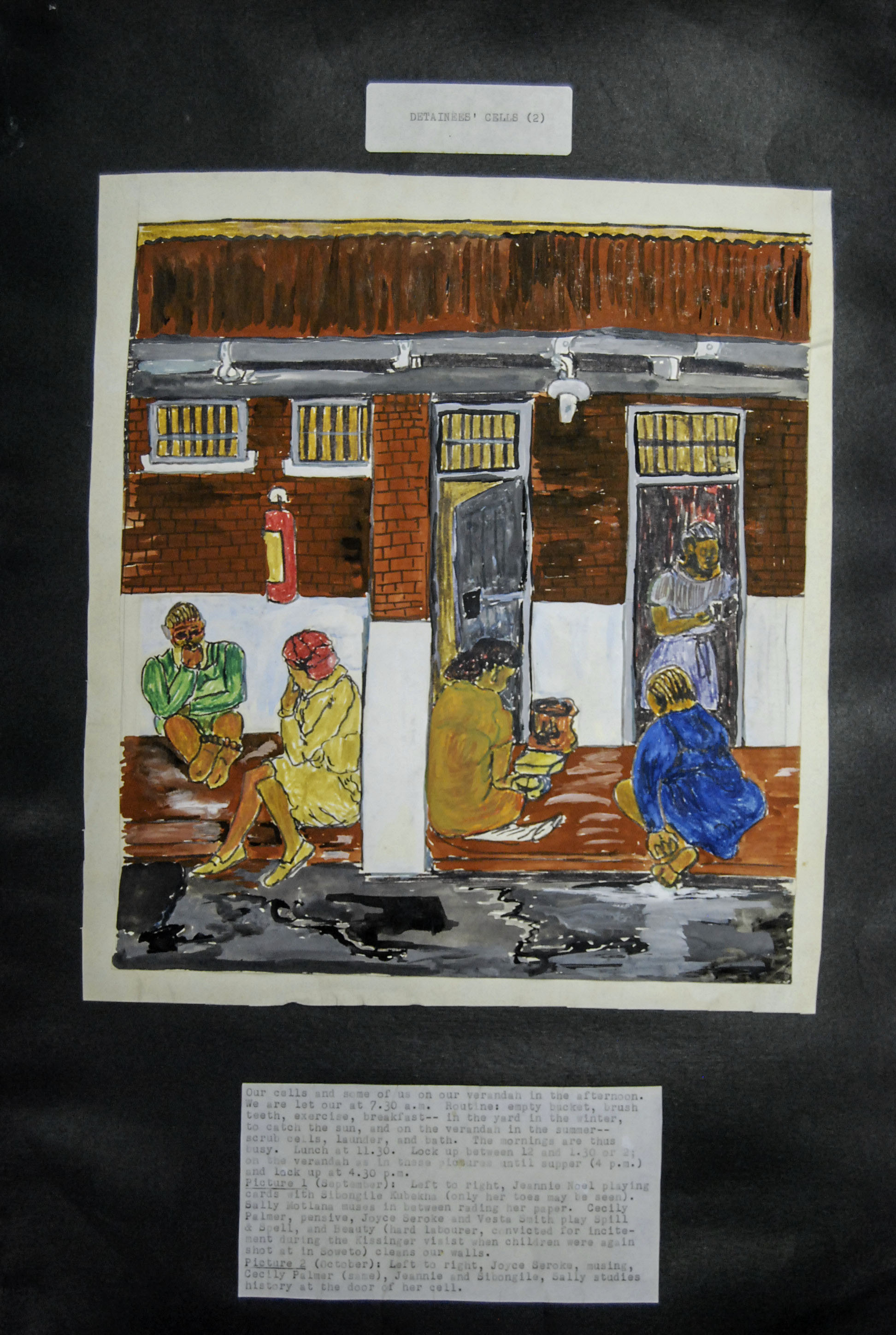

In mid-1976, shortly after the Soweto student uprisings, Meer and 10 other women were arrested and held in solitary confinement under section 6 of the Terrorism Act. The other women were Winnie Madikizela-Mandela‚ Jeanie Noel‚ Sibongile Kubeka‚ Sally Motlana‚ Cecily Palmer‚ Joyce Seroke‚ Vesta Smith‚ Jane Phakathi‚ Deborah Mashoba and Lorraine Tabane.

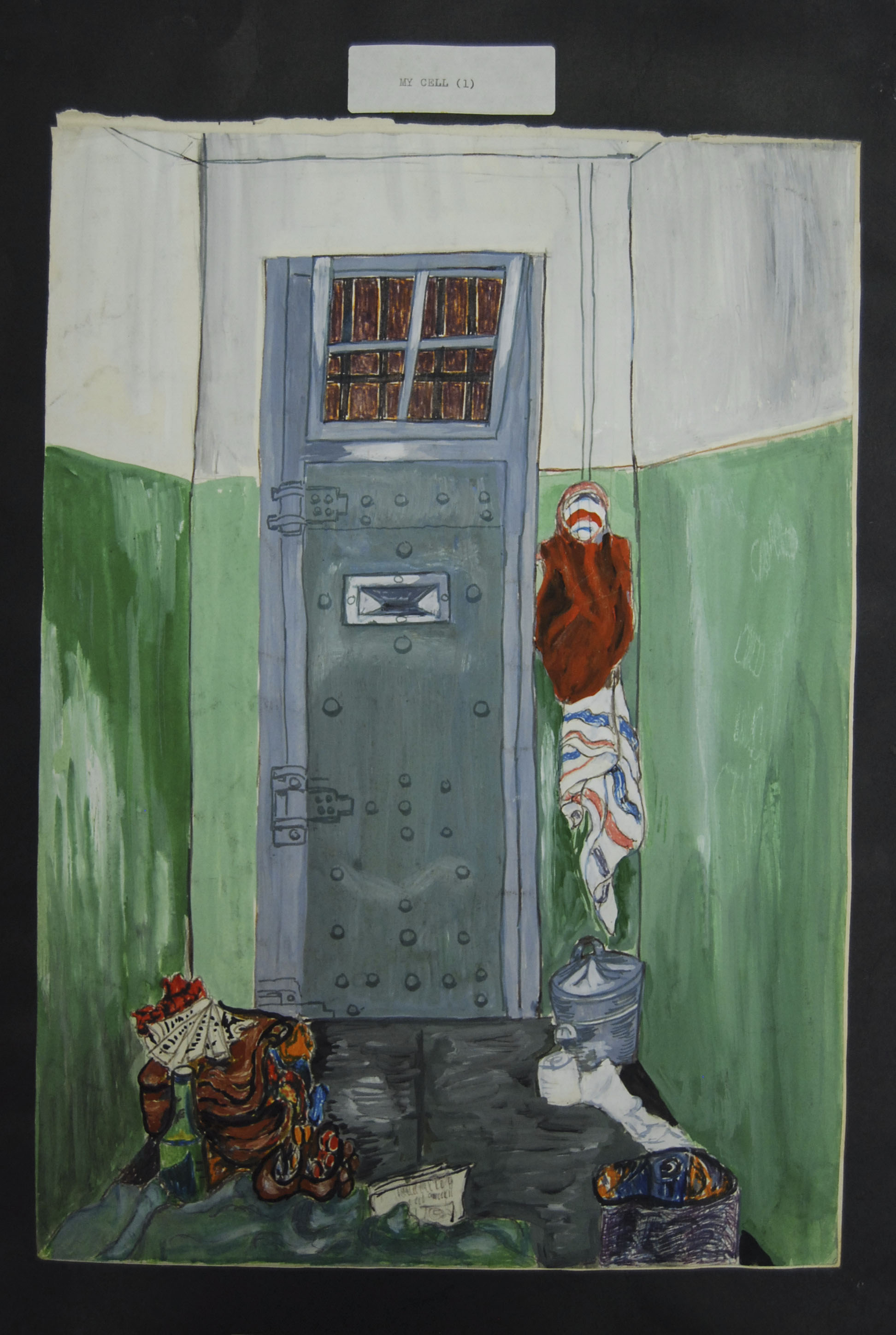

Meer’s 20 paintings were made during her time in Johannesburg’s Women’s Jail, at what is now Constitution Hill, after she received paints from a family member. Her artworks were smuggled out of the prison with the help of Madikizela-Mandela and their lawyer.

Artist Andrew Venter mentions being in possession of the paintings before they were smuggled out of the country, which forms part of the mysterious trajectory that seems to envelop the movement of the paintings until they were finally returned to the site where they were created. The exhibition, Prison Diaries, of all 20 paintings opened in mid-August.

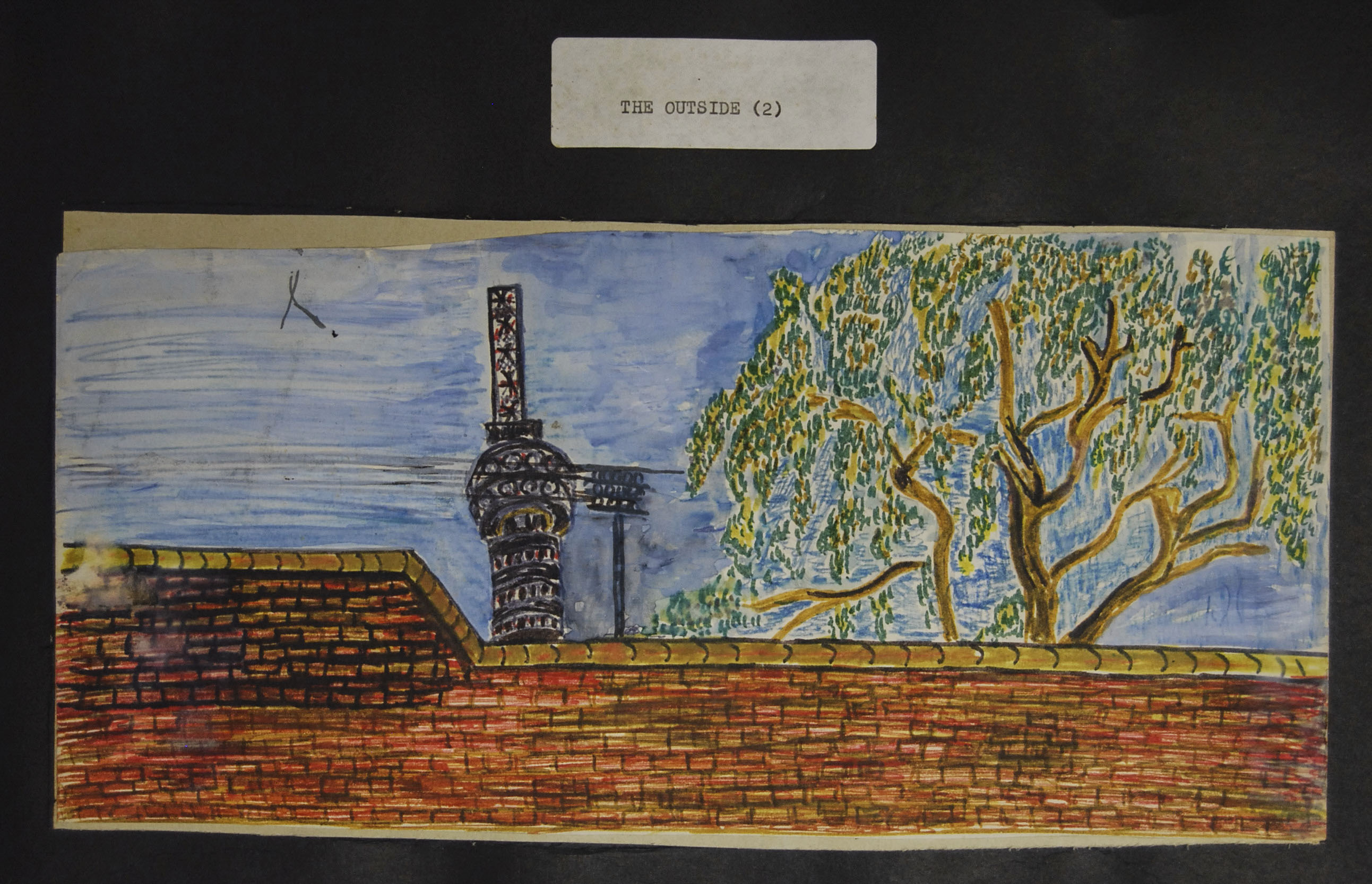

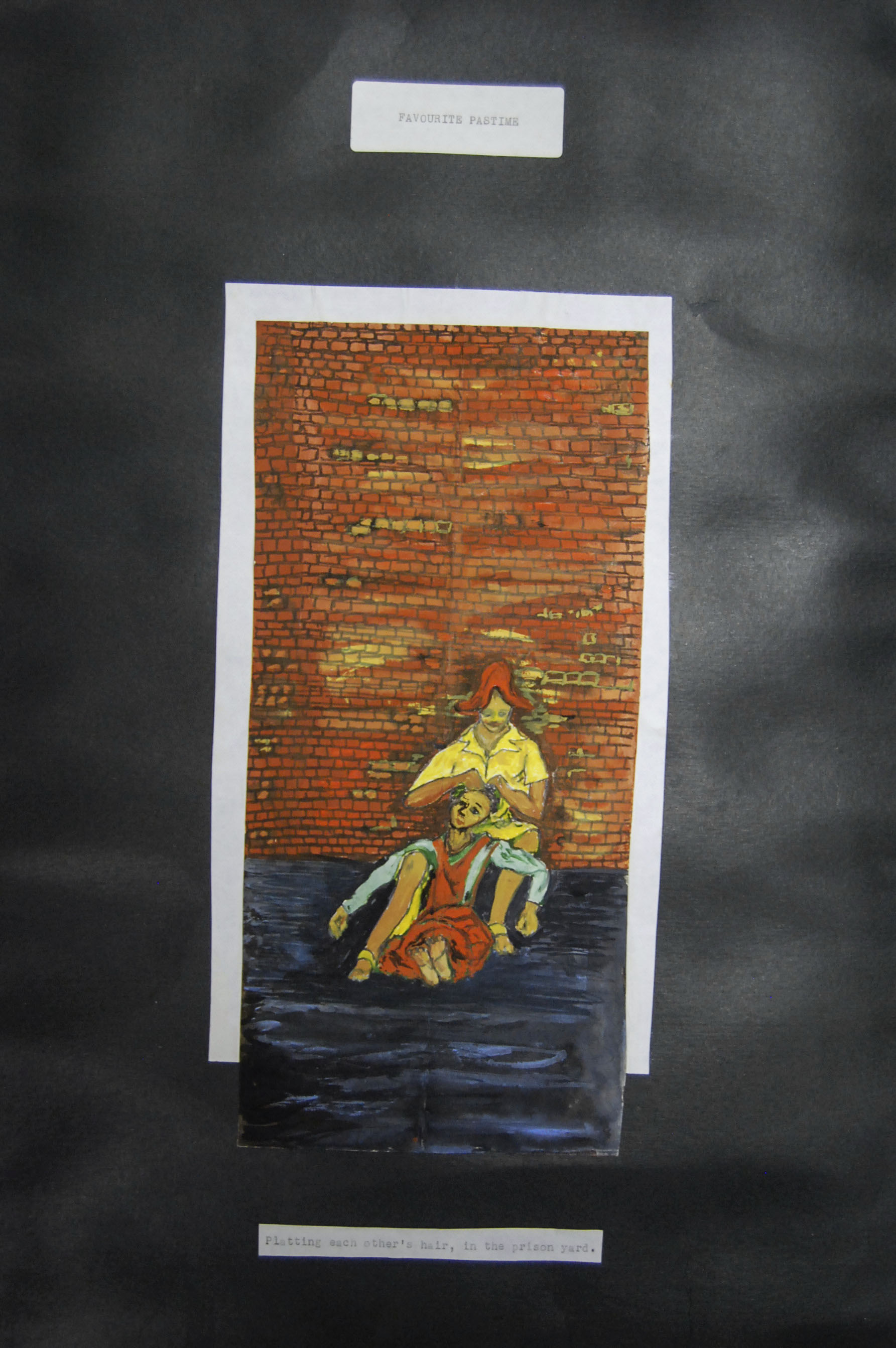

In Meer’s spirit of defiance and determination to defeat the prison system, each of the paintings represents a stolen moment that either implicated or slipped past the watchful eye of authority and power.

My interest in the paintings thus led to an exploration of how such historical material could challenge the dominant narratives of women’s participation in liberation movements and other sociopolitical matters. They became particularly appealing because they refuted what appears to be a narrowly political and masculine approach towards representing history. The mundane activities the women are shown doing in the paintings propose a way to challenge what has evidently become a stereotypical portrayal of the history of South Africa’s liberation struggle.

At the core of the research was how narratives depicted in Meer’s paintings start to function as primary sources with evidential value that may offer the public, scholars and researchers the opportunity to use Constitution Hill in a much more meaningful way. The research thus also advocated for the paintings to be conserved and permanently displayed at the site to give a fuller and richer experience.

Constitution Hill is part of a group of post-apartheid museums that emerged as heritage sites and sites of consciousness directed at redressing issues from a painful history and the representation of that history. It is not only a unique site because it is also the home of the Constitutional Court, but because the people who were incarcerated within its walls were not always political prisoners. As a result it also becomes part of monuments, museums or sites of trauma that sometimes come across as contradictory and in some instances seem to manipulate history for political objectives where certain narratives obscure an understanding of the history in particular ways.

Meer’s paintings in some way demonstrate how there is a sense of exclusivity and elitism that limits the representation of other kinds of narratives. Although the paintings appear to enhance or fit into the dominant political narrative of famous people incarcerated during the struggle for democracy and who have been given iconic status or are commemorated in various ways in the museum, they also expose the potential to shift a prevailing understanding of what the struggle was about and create an opportunity for alternate platforms for other narratives to be heard.

These alternate narratives are revealed in Meer’s depiction of acts of pleasure and enjoyment such as painting, playing cards or even plaiting hair. In some instances she focuses on the harsh realities of prison life, where documentation seems to take precedence over self-expression.

Painting could have also been a way to transcend the confines of the prison, because creativity defies the prison’s attempts to make prisoners conform and act in predictable ways — in other words, prisoners can resist attempts to imprison their minds. Most of the paintings therefore have a voyeuristic quality, almost as if Meer was painting as an observer rather than a detainee. It seems she did not only want to show the mundane routine of being in prison but also, as suggested in her diary entry, the very act of painting became political and a form of resistance.

The narration of the struggle narrative has been a profoundly gendered story, one that focuses on masculine public action and populist ideals, but portrays women as background participants. Women are usually framed as nurturers and supporters — “the mothers” of the nation — and most times rendered invisible.

Cultural forms of resistance are also not well represented and recognised in political movements, especially those created by women. Meer’s paintings offer something qualitatively different and acknowledge the role of art and culture as part of the resistance against oppression. Resistance in the liberation movement should not only be understood in political terms, but also as a culmination of ideas aimed at defying an oppressive regime.

The paintings are significant because they suggest a broader understanding of the history of the Women’s Jail, but they also highlight issues of exclusivity about who gets commemorated and in what manner. They therefore act as agents for the unmediated voices of less articulate and less visible women who were also part of this historical site, but whose traces are quickly vanishing into the cracks of history.