The FSB appears to have upped its game as the extent of unpaid benefits emerges and public scrutiny and pressure intensify.

The Financial Services Board (FSB) has moved to clarify its efforts to resolve the ballooning problem of unclaimed pension benefits, even as civil society campaigners step up a drive to help workers to reclaim billions owed to them.

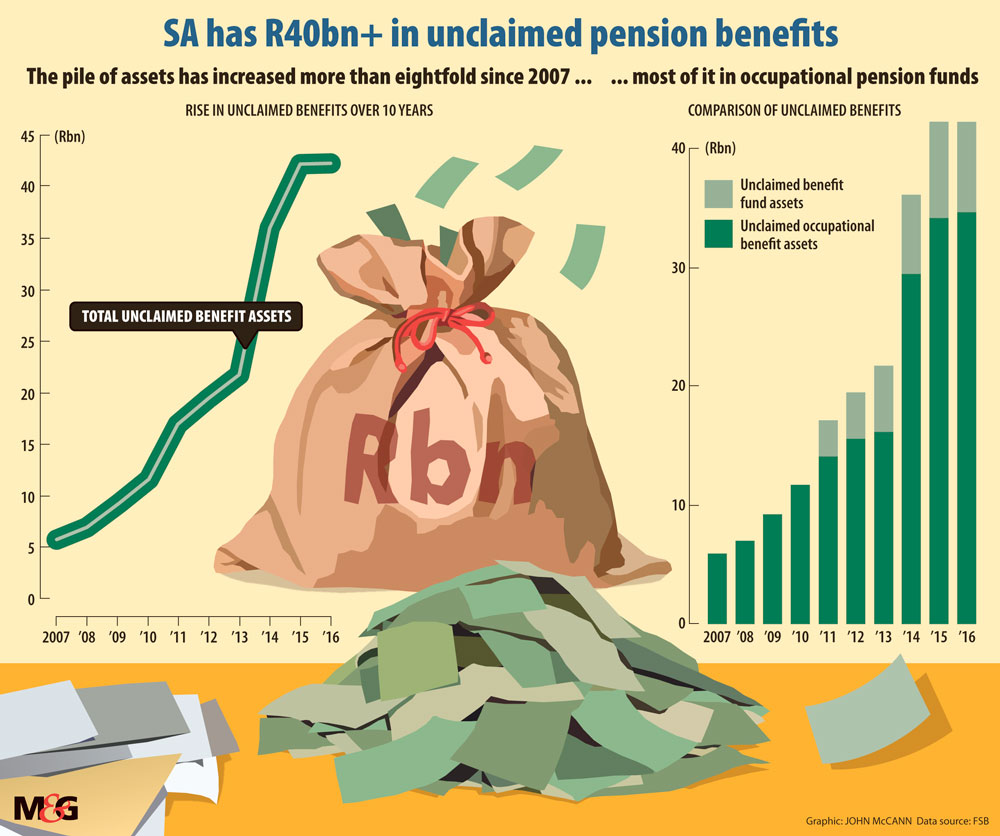

By 2016, more than R42-billion in unclaimed benefits had been amassed in the pensions system, the FSB said at a media roundtable earlier this week.

About R7.6-billion is held in specially created unclaimed benefits preservation funds, and about R34.7-billion is held in occupational funds, or retirement funds, created by employers for their employees and which are active.

The amount of money unclaimed by beneficiaries began to rise dramatically from about 2010, with a sharp leap between 2013 and 2014, FSB data shows.

But, said Takalani Lukhaimane, the manager for pensions enforcement and surveillance, greater reporting and disclosure requirements from funds relating to unclaimed benefits and changes to how funds classify these assets have in part contributed to the increases.

This can be seen in the 66% spike in unclaimed benefits between 2013 and 2014 after two large funds reclassified about R11-billion in assets as unclaimed benefits.

About 60% of the unclaimed benefits in occupational funds belong to employees in the mining, motor, metal and engineering industries.

Chief executive Dume Tshidi said the historical problem of tracing beneficiaries remained, some of whom worked in the pre-democratic era when apartheid identity documents did not correspond with those issued post-1994 and when many workers were forced to lie about their identities, including using false names and ID numbers, to gain employment.

Lukhaimane said it was difficult to trace beneficiaries who were migrant workers from neighbouring countries or from rural areas. And the problem of the misuse or duplication of ID numbers continues today in some sectors, she said, for example in the security industry

“Because the funds don’t have accurate information, because of historic or current problem, it’s difficult for them to trace somebody,” she said.

The cost of tracing a beneficiary can be more than the amount owed to them, Lukhaimane said.

Just under 17% of the members in these funds are owed less than R100. For about 26% of members, the amount owed is less than R250. The FSB said these small amounts represent a very small portion of the total value of unclaimed benefits — about 0.6% and 2% respectively.

But civil society campaigners argue that vested industry interests, such as large pension funds administrators, are not doing enough to trace beneficiaries and that the regulator is not adequately ensuring they pay claimants out.

Moffat Chauke, of the Unpaid Benefits Campaign, said fund administrators do not do a good enough job of tracing beneficiaries. He said the campaign began organising in 2015 in the Vaal area.

“They [administrators] don’t use home affairs, they haven’t contacted the revenue [service],” Chauke said, adding that tracing could be done using cellphones and the Regulation of Interception of Communications and Provision of Communication-related Information Act (Rica).

Public interest in the question of unclaimed benefits has grown since the FSB found itself in a court battle with the former deputy registrar for pension funds, Rosemary Hunter, which began in 2016.

Hunter took the FSB to court over its handling of the so-called “cancellations project” — a long-running effort by the FSB to cancel thousands of dormant or orphaned pensions funds.

Hunter raised red flags over what she said were unlawful steps taken by the FSB to close these funds, without properly ensuring that they had no assets or liabilities, or that money had been transferred to unpaid benefit funds.

The possible prejudice to members could run into billions of rands. The FSB has strenuously denied Hunter’s claims.

The high court ruled against Hunter at the end of last year, refusing her leave to appeal the case. But, after taking the matter to the Supreme Court of Appeal, which also dismissed her case, the Constitutional Court will hear Hunter’s application for leave to appeal and arguments on its merits in February next year.

The Unpaid Benefits Campaign and fellow nongovernmental organisation Right2Know have publicly supported Hunter.

But the problem is broader than the cancellations project, said Dale McKinley, a national working group member of Right2Know.

“The [regulator] has not been doing its job,” he said, arguing that it has allowed industry players to “cynically” sit on the money, earning high administration fees.

The industry has not been pro-actively tracing individuals, particularly people who are hard to find, such as migrant workers from neighbouring countries.

A secondary problem is that of “institutional mazes and bureaucracy”, which impedes beneficiaries when they try to claim the money owed to them, he said.

The growth in the number of unclaimed benefits in recent years suggests the majority were not to people who were working during apartheid but rather to people who had retired or been retrenched in the past 15 to 20 years, McKinley said.

The FSB denied it has intensified its work to address the unclaimed benefits problem because of increased public scrutiny and the Hunter court battle.

Since 2007, more than R22-billion in unclaimed benefits has been paid out to almost one million beneficiaries, according to financial records supplied by funds to the registrar’s office. About R18-billion was paid out in the past five years, with an average of about R26 787 a member.

From 2009, when the FSB began requiring more disclosure on unclaimed benefit funds, it continued to provide resources for the matter as more information came to light, Lukhaimane said.

In August, it launched a search engine on its website using information from funds and administrators to help members of the public to find out whether money is due to them.

It will be launching an SMS service in the coming months to reach potential beneficiaries who may not have internet access.

As far back as 2004, the FSB proposed legislative changes to house all unclaimed benefits under one central fund. The proposal was not realised, but this year the FSB has again proposed amendments to the Pension Fund Act to provide for a central fund.

This could be expanded to include the unclaimed money sitting in other industries, such as the insurance and banking sectors.

Aside from unclaimed funds in the pensions system, there are billions in unclaimed funds sitting in life insurance policies and collective investment schemes.

In addition, the FSB does not regulate some state-linked pension funds, such as the Government Employees Pension Fund, the Transnet Retirement Fund and the Post Office Retirement Fund.

Rosemary Lightbody, a senior policy adviser of the Association for Savings and Investment South Africa (Asisa), said that, as of December 31 2016, there was another R4.4-billion in unclaimed assets in long-term insurance policies and collective investment schemes.

Asisa’s standard on unclaimed assets commits its members to honouring unclaimed policy and investment benefit claims by rightful owners “no matter how long it takes”, she said.

This was the first set of data received from member companies since the standard was extended beyond life insurers, effective from the beginning of 2016, she said.

In the six-month period between July 1 and December 31 2016, more than 37 000 beneficiaries or investors were traced and paid out assets worth R5.6-billion, she said.

Companies are required to start tracing policyholders, beneficiaries or investors within six months of the assets becoming payable, Lightbody said. Reports received from member companies show at least four tracing initiatives per case, including the use of tracing agencies, private investigators, the department of home affairs and credit bureaux, she said.

Members also make use of social media, such as Facebook and LinkedIn, and approach professional membership bodies.

• For more information on the FSB’s unclaimed benefits search process, go to: mg.co.za/FSBprocess

• Members of the public who would like to know if there are any possible unclaimed benefits due to them can access the online search engine at mg.co.za/FSBsearch